The Old Spanish Trail Highway in Texas

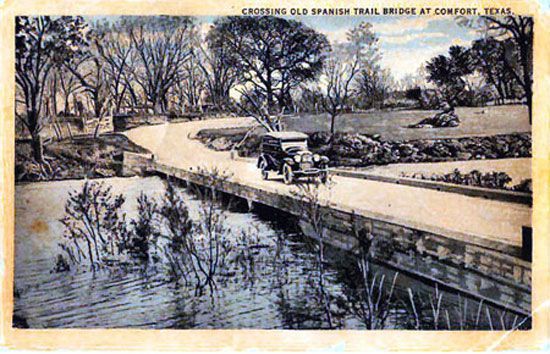

The concept of the first Southern transcontinental highway was begun in Mobile, Alabama. In 1915 civic leaders in the Gulf coast city announced plans for a better road to the Atlantic. At the same time, cities in Texas began to float ideas for improved access to New Orleans. In what became a series of annual conventions following the meeting held in Pensacola, Florida in 1916, a very grand vision arose for a continuous highway from the Atlantic at St. Augustine in Florida to the Pacific in San Diego California, a distance of 2,817 miles. While this does not exactly match the route of the modern IH 10 interstate, which runs from Jacksonville, Florida, to Los Angeles, California, it is fairly close and certainly demonstrated remarkable foresight at a time when there did not yet exist one hundred miles of continuously paved highway in the whole of Texas. The route was given a picturesque name, “The Old Spanish Trail,” as a marketing tool, much as naming the first Northern transcontinental route from New York to San Francisco, “The Lincoln Highway,” first proposed in 1912. The names were designed to capture the imagination of cities and counties along the proposed routes and encourage participation in the construction of the route, as the OST organization could not even begin to pay for all the roads and bridges that would be required.

Responsibility for the OST was given to each state along the route. State organizers approached counties, cities and individuals for support and donations. As the idea caught on, the potential for attracting the growing numbers of tourists using cars for vacations and sightseeing became increasingly apparent. Automobile tourism was in its infancy. Few roads were numbered and almost none provided with signs. Locals might know where they were but not tourists. Now folks wanting to see more of the country could buy Old Spanish Trail maps and guide books, that included directions where to find gas, food and accommodation. As they drove they would follow OST route markers attached to lamp posts within towns and painted on trees, telephone poles and fence posts in the country. OST signage consisted of a highly visible and distinctive arrangement of a thin red band above a thick white middle section with either the letters OST or a directional arrow, and a thin yellow stripe at the bottom.

San Antonio was not originally included in the route proposed by the OST. Instead it was to go through the growing cities of Dallas and Fort Worth. A large delegation from San Antonio packed the 1919 OST conference in Houston and rectified the situation from the city’s point of view. San Antonio even assumed leadership of the OST within the state. A man essentially passing through the city, Harral Ayers, was offered the position of OST leader within Texas. He had experienced great success juggling large projects with difficult financial arrangements, but was obliged to leave a thriving career in New York and surrounding states for health reasons. Aiming for Hawaii, but with no definite plans, he sailed to Galveston and boarded a train for California. During a break in his trip to visit friends and go hunting in San Antonio, Ayers went to the dentist where an x-ray revealed an infection underneath an old gold crown. With treatment, his ill health of some twenty years quickly improved. He chose the historic Gunter Hotel on Houston Street for the OST headquarters. The first hostelry on the site dates back to 1867, when the street was still called El Paseo del Rio, four years before being renamed Houston.

As the Old Spanish Trail Highway progressed from Houston to San Antonio the route never strayed too far from the main Southern Pacific railroad tracks. This was because a right of way was already established. Wagons and early cars had being following the line for years. Very significantly, it also allowed for the easy transportation of road materials and equipment. Most highways were still using Macadam construction, requiring successive layers of rocks of descending size with a top layer of gravel. Enormous quantities of rock were required. Early trucks could not carry heavy loads over great distances in large part due to lagging tire technology and the poor state of the roads themselves. However, they were well suited for short haul. They were loaded from trains at rail sidings along the route and in this way the road made good progress through the wealthier and more populated counties. Without a hard surface, the growing number of vehicles and the increasingly heavy trucks faced many problems along the way. Not all of these were accidental. For some reason, even in the height of summer, a wet spot on the road between Weimer and Schulenburg just would not go away. Drivers familiar with the road would gun their engines in an effort to get across, but frequently found themselves stuck yet again. A local farmer, who just happened to be nearby with a team of horses, was more than willing to tow them out for a mere $5.00. This at a time when a gallon of gas cost 25 cents. The OST did deviate from the railroads if counties along the way offered greater participation. Gonzales County did just that and so the OST swung south between Flatonia and Seguin, avoiding Luling at the southern tip of Caldwell County. Nearby Shiner, in Lavaca County, with its famous brewery, was not on the OST directly but its brew master, Kosmos Spoetzl, well known for marketing his beer personally from the back of a Ford Model T certainly took advantage of the improved road. Being near the new main highway brought an additional advantage to railroad access.

The Old Spanish Trail authorities had a decision to make at San Antonio. Should the route stay close to the Southern Pacific Railroad through Hondo and Del Rio to reach El Paso or should it follow what freighters and stage coach drivers referred to as the high road, via the Hill Country and then through Junction, Sonora and Ozona. Both routes had their merits. The critical factor that informed their decision was simple: money. Kerr County was the first in Texas to sign up as an OST participant. Many of its most prominent citizens including the Schreiner family, who had been instrumental in achieving a difficult rail connection thirty years before, provided significant donations. Among other donors was the Butt family, the founders of the giant HEB grocery chain. The OST followed the “high road” because Hill Country residents were willing to pay to be on the prestigious road.

An alternative OST tourist route through the Hill Country went through Bandera County, a real advantage for the city, which never received a rail connection. The “Old Spanish Trail Restaurant” in Bandera, opened in 1921, is one of the last remaining originally named eating establishments along the OST, despite a near disastrous fire in 2007. Hill Country Counties were not slow to promote their region. The OST was the golden opportunity of the age to be literally put on the map. This early foresight paid off when, fifty years later, Interstate 10 followed the same route, once again avoiding the older and marginally shorter route to El Paso.

In 1922 Congress set about making sure that the near disastrous transportation experiences encountered by the military during World War One would not be repeated. During the conflict railroads became so entangled that the government had to take them over, although the problem was more a lack of suitably long sidings than anything else. Troop and material movements over the nation’s underdeveloped road systems were almost as bad. Repeated long convoys of heavy trucks, most of which had solid tires, quickly ruined unpaved roads and lightweight bridges. To rectify this situation a national network of military highways was proposed. Harral Ayres, as the state leader of the Old Spanish Trail Association, and a civilian representative of San Antonio, one of the most important military cities in the country, successfully lobbied Washington politicians that the entire length of the OST be designated as a military highway, ensuring increased federal funding for its construction and improvement.

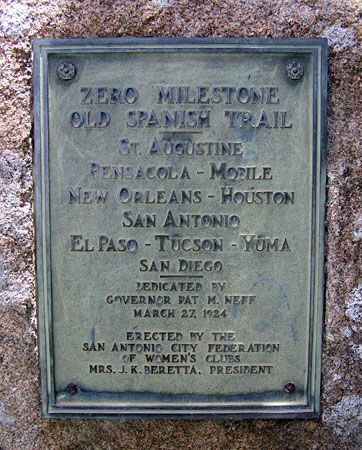

As the 1920s drew to a close, the original dream of a continuous highway across the south, from the Atlantic to the Pacific, was finally realized. Governor Neff dedicated an OST zero milestone outside San Antonio city hall in March 1924. It is still there today. Drivers were supposed to reset their perhaps unreliable odometers for the next leg of the journey at such markers, just as the first intrepid motorists had done twenty years earlier. The first ceremonial drive across the 2,817 miles of continuously improved road, lined with signs put up by each state, began in San Diego, California on April 4 1929. Their arrival in San Antonio was ceremoniously greeted with a dinner at, of course, the Gunter Hotel.

It had taken fourteen long years for the original vision of a southern transcontinental highway to be realized. The volunteer Old Spanish Trail Highway organization quickly faded away. States had been issuing official maps since 1927 and had taken responsibility for highway construction much earlier. Some OST ideas remained in a more subtle form. As early as 1923, beautification committees were formed to provide guidance on how roads, bridges, signs and rest areas should be designed. They even provided suggestions on how restaurants, gas stations and tourist camps should look, with particular emphasis on the use of attractive stone work. A few traces of their efforts remain today. The spirit of making the highway and stops along the route look as good as possible within an overall scheme continues today within the Texas Department of Transportation. Even so, the quality of the road still left much to be desired. The section through the Hill Country, now called Highway 87, was technically improved, but all this meant was that it had been graded and provided with ditches for drainage. Most sections within Texas remained unpaved. Along the Gulf coast the road surface consisted of crushed sea shells. Depression era projects made further improvements but some sections would remain of poor quality right up to the interstate era began, thirty years later.

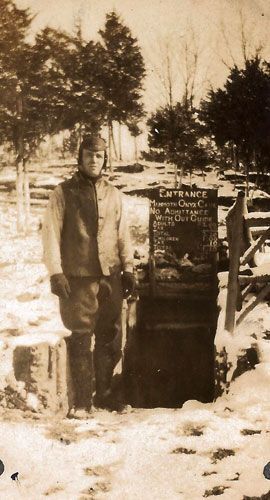

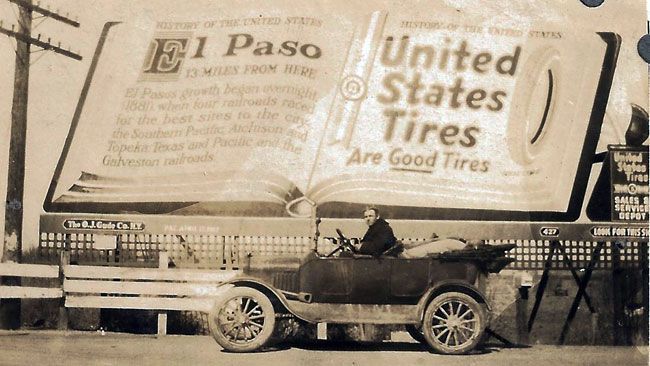

In 1924 a group of three men in their early 30s, including William Todt, decided to take a trip from their homes near West Point, New York down to Florida, along the entire length of the Old Spanish Trail, from the Atlantic to the Pacific and then back home via the Lincoln Highway. They drove a 1924 Ford Model T touring car, which they sold upon their return for $10. The trip took several months. The road system at that time was still in its infancy. Many states had introduced their own numbering individual numbering systems and privately organized routes such as the OST and Lincoln Highway were still very important. It is almost certain that they used guides published by these organizations to help them find fuel, food and accommodation along the way, not to forget the importance of their colored route markers and maps. Here are some pictures of their journey generously supplied by William's son, Bill, who recalls being told about their trip of a lifetime by his father many years ago.

Although the trip and the tales he told his son about it all happened long ago, young Bill paid a lot of attention to the saga of this epic sojourn made by his father. Their Ford Model T coped really well with the rigors of the trip over many, many miles of unpaved roads. Other types of vehicle, not as common or as rugged as the T, resisted being repaired by local blacksmiths who had to send for parts from far, far away. They got used to see Packards and other large cars strand their passengers for weeks at a time. The roads became worse the further west they went. Any pavement or even hard surface would disappear at city limits. The heat and the dust wreaked havoc on both vehicle and passengers alike. The group was traveling on the slimmest of budgets. If they came across a ferry that charged 10 cents during the day but only 5 cents in the evening, they would choose to wait for the lower rate. They slept in, near and even under their T as often as possible. William Todt figured that each tire lasted about a 1,000 miles. The journey took the entire summer of 1924. Even today most people would think twice about such a long trek, in a modern car with air-conditioning and the interstate system.

Old Spanish Trail Timeline

━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━

1915

Gulf Coast highway idea proposed in Mobile, Alabama

━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━

1916

Southern transcontinental highway idea proposed at first conference. "Old Spanish Trail" name adopted

━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━

1917

Somewhat reluctantly, the Texas Department of Transportation, TxDOT, is created, to enable the state to receive Federal road funds. Texas highways given state issued numbers. The OST between Houston and San Antonio becomes State Highway 3

━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━

1919

San Antonio added to the route, becomes HQ of OST in Texas.

━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━

1919

Kerr County becomes first county in Texas to sign up for OST participation

━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━

1920

Harral Ayers chosen to lead OST in Texas, chooses Gunter Hotel in San Antonio as his HQ

━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━

1921

Old Spanish Trail restaurant opens in Bandera, along a subsidiary tourist route through the Hill Country

━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━

1922

OST designated a military highway, thus securing additional federal funding

━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━

1924

Ceremonial OST marker installed outside San Antonio City Hall by Governor Pat Neff

━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━

1924

Stare wide gasoline tax generates additional funds for highways improvements

━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━

1925

National highway numbering system introduced. OST between Houston and San Antonio becomes Highway 90

━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━

1929

First ceremonial drive of the entire 2,817 mile coast to coast route is undertaken

Frank Crothers at the San Antonio bicycle race track.

Transportation Museum

CONTACT US TODAY

Phone:

210-490-3554 (Only on Weekends)

Email:

info@txtm.org

Physical Address

11731 Wetmore Rd.

San Antonio TX 78247

Please Contact Us for Our Mailing Address

All Rights Reserved | Texas Transportation Museum