The Railroad and the Military in San Antonio

Much of the information on this page was supplied by the US Army Medical Department Museum located at Fort Sam Houston, San Antonio. This museum is well worth a visit to get the fascinating story of how the military has always used forward thinking to make sure military and civilian personnel gets the best medical care available, often under the most difficult of circumstances.

San Antonio was the last major city in the USA to achieve railroad service. Some commentators with a poor understanding of history and economics attribute this to some kind of conspiracy to keep them out but the truth is a lot more interesting. Simple history and geography played a significant role. Texas was originally settled from the south. San Antonio was founded by the Spanish in 1718 on the banks of a generous, free flowing river at the half way point between the main Rio Grande crossing near modern Eagle Pass and Nacogdoches at the edge of their empire near the border of modern Louisiana. Newly independent Mexico did not enjoy much greater success in settling the northern extreme of their country. When Texas declared independence in 1836, San Antonio was isolated from the ports of Indianola, Port Lavaca and Galveston which took on a much larger role as the gateways to the state. When Texas became the 28th state in the Union ten years later, this trend only intensified.

While coastal areas boomed, San Antonio, situated in the interior of the state, became ever more isolated. The United States army, through a series of forts, had helped to tame the region and make the city secure but its prospects looked dim unless it could achieve better communication with the outside world. Towards that end, in 1850 both the city of San Antonio and the county of Bexar invested $50,000 each ($13 million in modern money) in a bold initiative to build a rail line, to be called the San Antonio and Mexican Gulf Railroad, between both Indianola and Port Lavaca, then vying for the position of biggest port in the state, and San Antonio, a distance of some 130 miles. It took a mule drawn wagon train almost two weeks to make the arduous journey, over primitive roads without a single river bridge. Unfortunately the company was unable to fulfill its promises. By the time the civil war broke out eleven years later in 1861 it had only managed to lay tracks as far as Victoria and even these were pulled up by the Confederates to prevent their use by potential invading Federal forces.

Fort Sam Houston was established very close to the first large freight yard built in San Antonio. Named East Yard it, like the army base, is still in operation today only now a major interstate, IH 35, is located between the two. A spur line was built right into the camp from the yard. These tracks were not removed until the early 1990s and a rail bridge over the freeway at the current main entrance to FSH is still in place. Through many wars these tracks provided ready access to the rail system to the army. San Antonio became a military city. No other city in Texas, certainly not Dallas, Fort Worth, Houston or Austin comes anywhere close to the number of facilities created here.

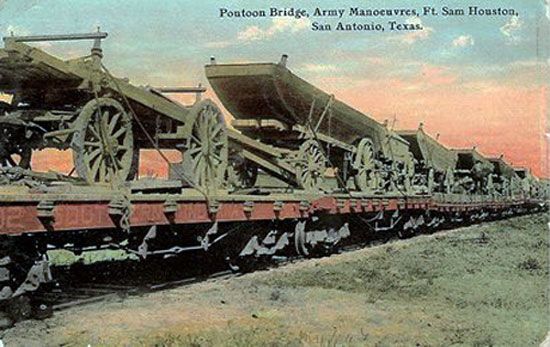

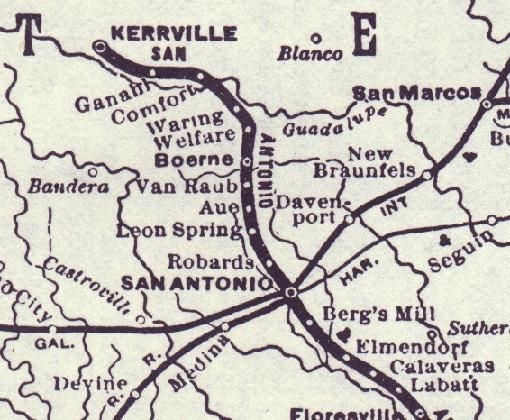

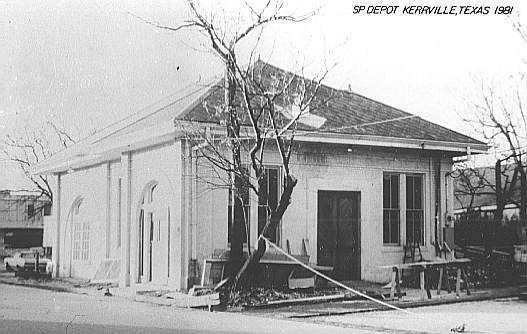

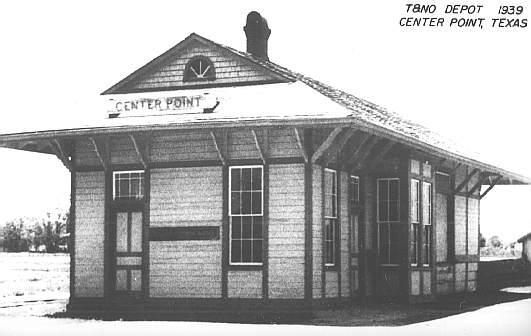

As the city grew around FSH, it became increasingly difficult for the army to conduct live weapon firing practice and maneuvers there. The greater range and fire power of the weapons themselves only added to the problem. Suitable sites for training purposes were required and the new San Antonio & Aransas Pass lines into the Hill Country towards Fredericksburg provided some good options that had ready access to the rail system. In the 1890s a site near Leon Springs was leased and found to be most suitable. It was almost completely undeveloped and so certain essential facilities, such as water wells had to be created providing training opportunities for the Corps of Engineers. Further along the line, another site belonging to Mrs. Jennie de Ganahl was leased for rifle practice. The training site was close to the depot which was also served nearby Center Point. The Ganahls were hoping a new community would be formed closer to the depot but this never materialized. At the end of the line in Kerrville, more land was leased, again close to the depot, for artillery practice. Facilities to take care of horses were created at each point along with secure storage facilities for ammunition and other military equipment.

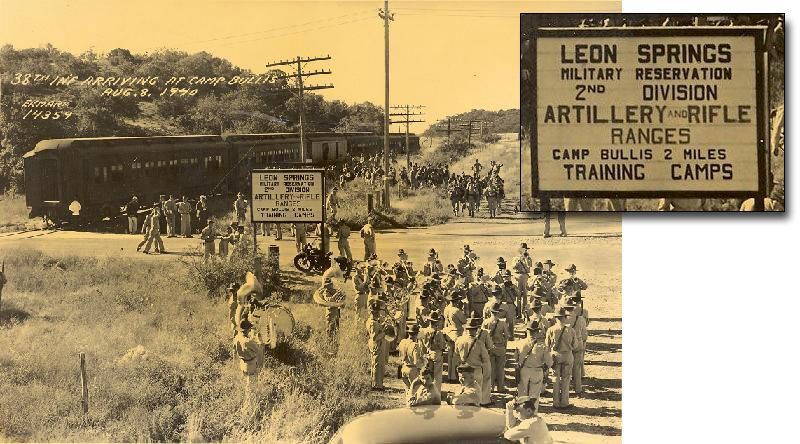

The land at Leon Springs was formally acquired in 1908 and a small network of rails was created within the camp to cater to the quartermaster stores and the horse care facilities. The other two sites returned to civilian usage. Originally known as the Leon Springs Military Reservation, the camp was briefly known as Camp Funston before taking on its current name, Camp Stanley, in 1917. It was at this time that the training needs created by the rapid expansion of the army during World War One became an acute problem for the army. Once again the increasing range of military rifles and other weaponry necessitated the acquisition of even more land and more ranches to the south of the reservation were acquired. The new camp, named Camp Bullis, after the very successful Indian fighter, General John Bullis, stretched five miles south to the edge of Lockhill-Selma and the San Antonio & Aransas Pass railroad.

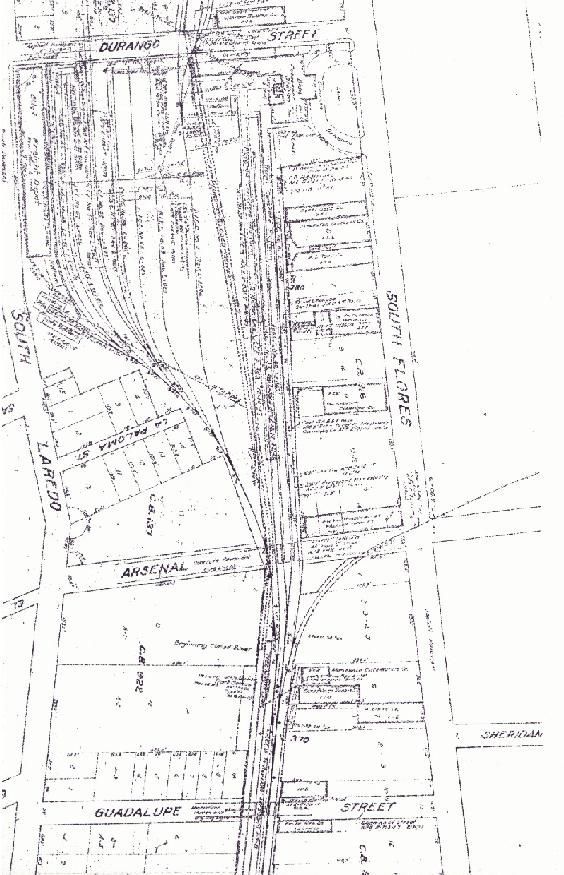

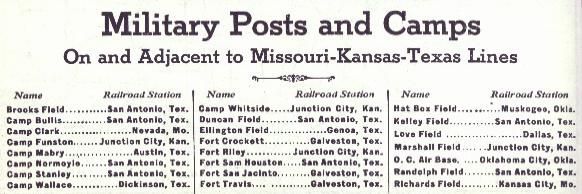

It was also at this time that the Arsenal, just south of downtown San Antonio, was greatly expanded. Coincidentally the construction of tracks into the new Missouri Kansas & Texas station very nearby at the corner of Flores and Durango facilitated the movement of material in and out of the facility, though a spur line from the San Antonio & Aransas Pass line had existed for some time prior to this. At this time the facility was much larger than the remaining main buildings currently in use by regional Texas grocery giant, H.E.B. Durango actually stopped at Flores and the acreage occupied by the military facility was much greater than today. As the city expanded around the Arsenal, just about any kind of military maneuvers and live fire training became absolutely impossible to conduct there. It was also determined that the storage of high quantities of potentially volatile military ordinance in the middle of a growing city was inadvisable. The army decided to move the munitions to Camp Stanley as its rail connections were already well established. However it would take quite some time for correct storage facilities to be completed.

It was also at this time that the Arsenal, just south of downtown San Antonio, was greatly expanded. Coincidentally the construction of tracks into the new Missouri Kansas & Texas station very nearby at the corner of Flores and Durango facilitated the movement of material in and out of the facility, though a spur line from the San Antonio & Aransas Pass line had existed for some time prior to this. At this time the facility was much larger than the remaining main buildings currently in use by regional Texas grocery giant, H.E.B. Durango actually stopped at Flores and the acreage occupied by the military facility was much greater than today. As the city expanded around the Arsenal, just about any kind of military maneuvers and live fire training became absolutely impossible to conduct there. It was also determined that the storage of high quantities of potentially volatile military ordinance in the middle of a growing city was inadvisable. The army decided to move the munitions to Camp Stanley as its rail connections were already well established. However it would take quite some time for correct storage facilities to be completed.

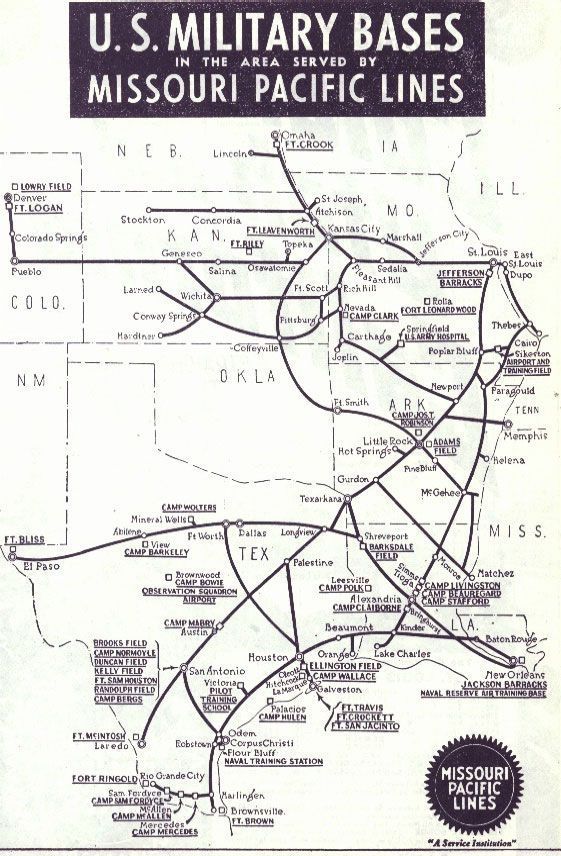

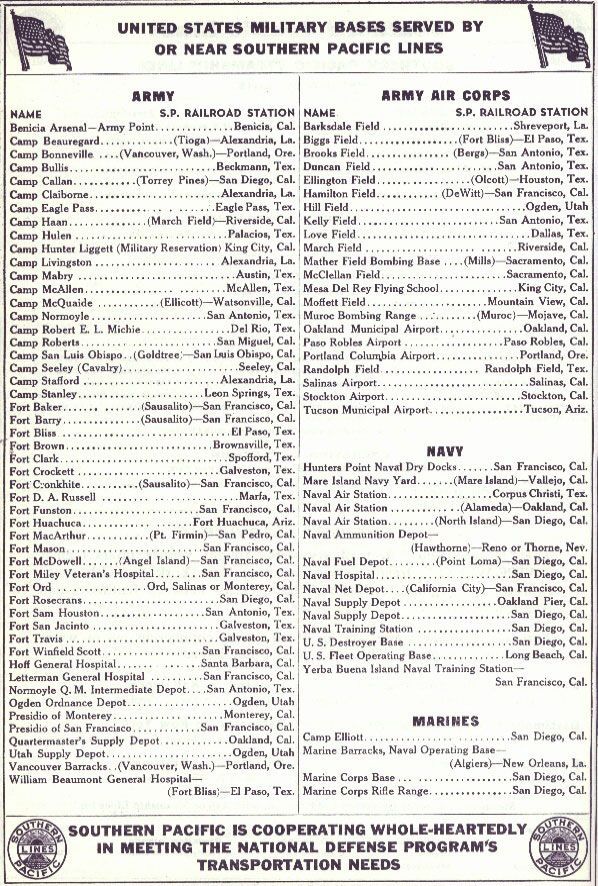

World War Two was the railroads' finest hour. As early as 1936, the Southern Pacific was heavily involved with the government in preparing for the war. In an attempt to avoid the gridlock and confusion that had bedeviled the national network during World War One, which led to all the railroads being taken over by the government from 1917 to 1920, the S.P. invested $123 Million on improvements. Of this, $88 Million was spent on new equipment. This included 156 steam locomotives, 73 diesel switchers, 14,158 freight cars of all kinds, 168 passenger cars and two diesel passenger locomotives. The expenditure also included the lengthening of existing sidings and building additional tracks. Without these improvements, the increase in both the length and frequency of trains would have quickly log jammed the system. With judicious fore thought, these problems which had caused all the difficulties in the earlier conflict were avoided during the Second World War. Working for the railroad was considered so important it could exempt employees from military service, though, of course, many a railroader did indeed go off to fight.

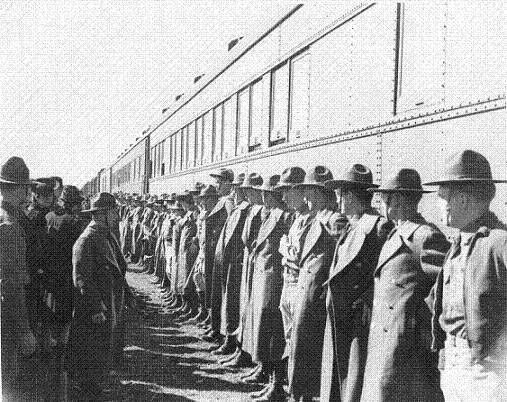

The growth of military bases in San Antonio and the extent of the S.P. network put the city and the railroad front and center in the war effort and both rose to the challenge magnificently. San Antonio experienced explosive growth during the crisis with an influx of both military and civilian workers on a unprecedented scale. The S.P. had 290 military installations along its routes, more than any other railroad in the nation. Aircraft factories on the west coast built 60% of all aircraft during the war and 44% of all ships. Almost all movement of oil during the war was handled by the railroads as oil tanker ships were diverted to support the military overseas. In 1944 the freight tonnage being moved by the S.P. was double the previous peace time peak of 1929. As early as 1940, the army and the S.P. began joint exercises. Moving entire battalions involved as many as a dozen or more trains. An armored division needed 75 trains to move all the men and equipment. The nation's railroads as a whole moved 97% of all organized troop movements during the war and 90% of all the military's freight and express requirements. The number of bases in San Antonio and South Texas and the port facilities in Houston and Corpus Christi, saw train movements of all types rise to unprecedented levels. Due to the careful preparations and improvements, the system was able to cope with all of the demands placed upon it.

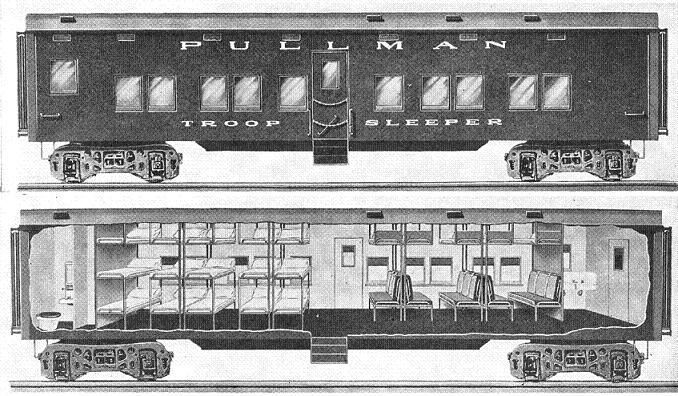

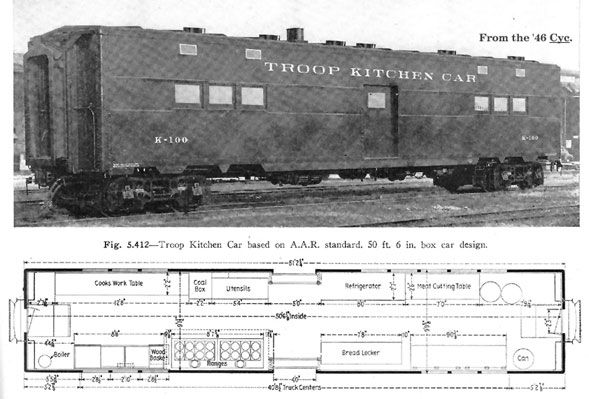

World War Two Era Troop Sleepers and Kitchen Car

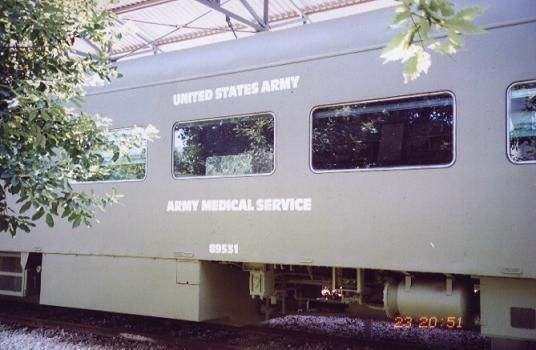

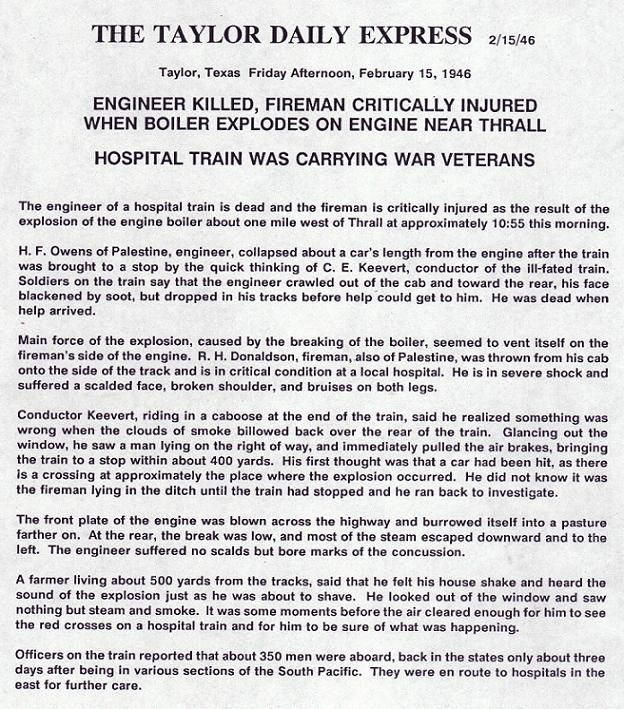

The US Army had no hospital trains cars in 1939, despite heavy usage of such cars in World War One. Realizing that using civilian equipment would be unworkable, plans were drawn up to create purpose built hospital cars and these became available at the end of 1943. During this conflict and the Korean War, military ambulance trains consisted of one baggage car, one kitchen car capable of supporting 400 persons, one personnel car (with accommodations for 10 doctors and 10 nurses) and six ambulance unit cars. Different cars would hold different types of wounded, and these would be detached at hospitals specializing in the required type of care. A typical ambulance car was capable of moving up to 27 patients. They were designed to work with steam locomotives and took their heat from the locomotives at the head of the train. Each car had its own generators with back up batteries to provide power when the generators were off line. Cars had power hook ups so they could be plugged into external power supplies at stations and sidings. This also enabled electrical power to be available to other cars in the event of any generator malfunctions along the train.

The role of Fort Sam Houston as a base for fighting units changed during World War Two. Almost by accident the facility was transformed into an army medical center, including hospitals, recuperation facilities and the training of field medics. It continues, with the nationally renowned Brooks Army Medical Center. Special trains carrying the wounded could be brought right inside the base. The use of trains to carry out the wounded has a long, long history, dating back to the civil war. The same trains that bought in ammunition would be filled with the injured for movement to better facilities. In the beginning this was a rough and crude business and the potential for the cross infection of so many men lying on filthy straw was very high. The US army is noted for its advanced thinking on the care of its wounded, however, and soon special hospital cars were purpose built that contributed greatly to the increase in the survival rates of military personnel. It also allowed for the movement of medical response teams much closer to the battlefield as it was realized that the reduction in the amount of time it took for soldiers to receive attention greatly increased their chances for more complete recuperation from their injuries.

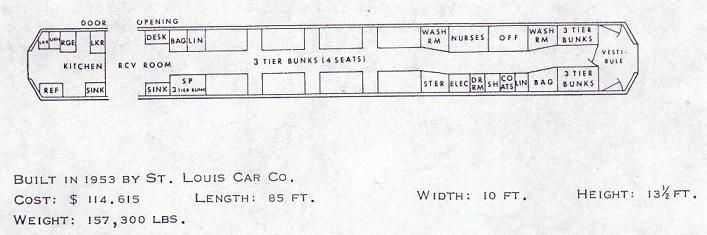

1953 US Army Medical Services car at the US Army Medical Department Museum, Fort Sam Houston

The complete history of this often disregarded aspect of warfare can be found at the excellent US Army Medical Department Museum at Fort Sam Houston. The details of how the wounded were moved, from horse drawn wagons, then trains, through Jeeps to helicopters are very well presented along with genuine examples of many types of military ambulance transportation. Included is a hospital railroad car built in the 1950s and actively used in Korea. This car, which is remarkably well preserved, represents the final evolution of military medical transportation by rail. By the 1960s just about all injured troops were being moved by specially equipped road vehicles, helicopters and jet airliners.

The use of the rails for the movement of men and material began its decline at this time. Once important rail lines on all kinds of bases were gradually removed as trucks and airplanes took over the role the trains once played. The end came in the 1990s when the tracks into Fort Sam Houston were removed and donated to the Texas Transportation Museum on Wetmore Road. Other bases, such as Lackland AFB, also had their rail connections removed around this time. When the Southern Pacific abandoned most of its line to Kerrville in 1971, its new terminus became Camp Stanley. As late as the first Gulf War to liberate Kuwait, the army was still using trains to move material from its storage facilities there. Often these trains went directly to Corpus Christi which has always been, and still remains, a significant military port facility. The tracks into Camp Stanley were finally removed around 2001 bringing to an end the once vital contributions made by the rail networks to all the branches of the military in and around San Antonio.

Transportation Museum

CONTACT US TODAY

Phone:

210-490-3554 (Only on Weekends)

Email:

info@txtm.org

Physical Address

11731 Wetmore Rd.

San Antonio TX 78247

Please Contact Us for Our Mailing Address

All Rights Reserved | Texas Transportation Museum