The Artesian Belt Railroad / The San Antonio Southern Railway

The chapter is indebted to Norman Porter, the Chairman of the Atascosa County Historical Commission. His generous assistance was invaluable. Mr. Porter has done a lot of research into the history of the county and the role of railroads in its development. Atascosa is lucky to have a man who is so dedicated to recording and preserving its history.

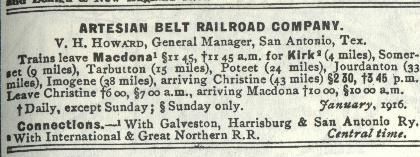

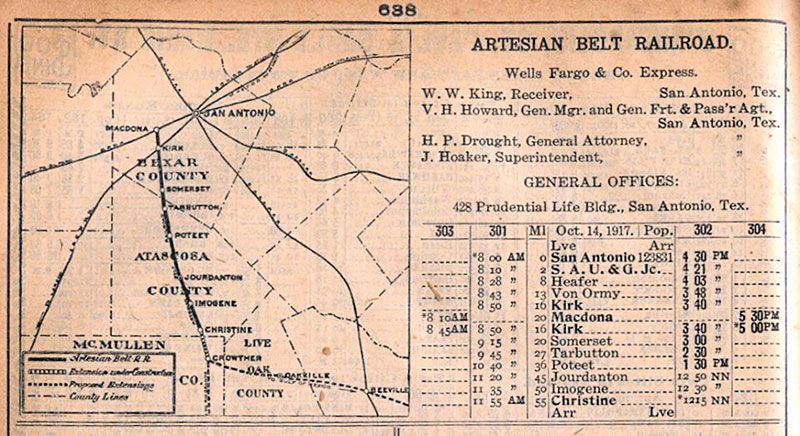

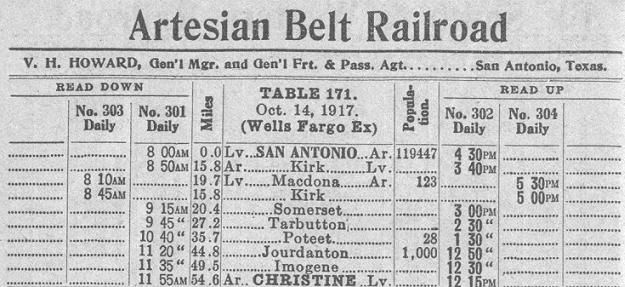

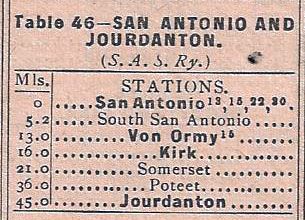

Artesian Belt entry in the 1916 "OFFICIAL RAILWAY GUIDE"

The Artesian Belt Railroad was formed in November 1908 by a private landowner, Charles Simmons. Simmons was an independently wealthy land colonizer. His father, and then he, both doctors, had made a fortune in the patent medicine business in St. Louis, Missouri. Charles, who had both a medical and a law degree, became a land speculator, or colonizer, after he came to Texas, for health reasons. He got into the business when he bought a ranch in Live Oak county for his son from George West, who would later become involved with the San Antonio Uvalde and Gulf railroad. West was forced to sell due to huge losses stemming from a drought. Regrettably, the son died and Simmons disposed of the ranch by subdividing it. This turned out to be very profitable. Delving into the "colonizing" business again, he purchased 95,000 acres, at $4.50 per acre, south of what is now Jourdanton but this time things proved to be more difficult. The land was divided into lots ranging from 10 to 640 acres, but the problem was no one could get there as there were neither roads nor rails to transport them to what had, up until that time, been a huge ranch with tens of thousands of cattle.

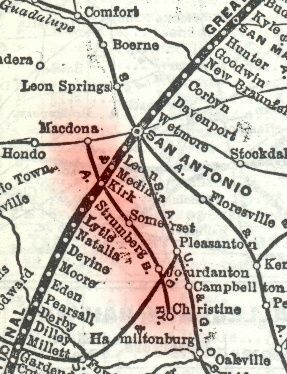

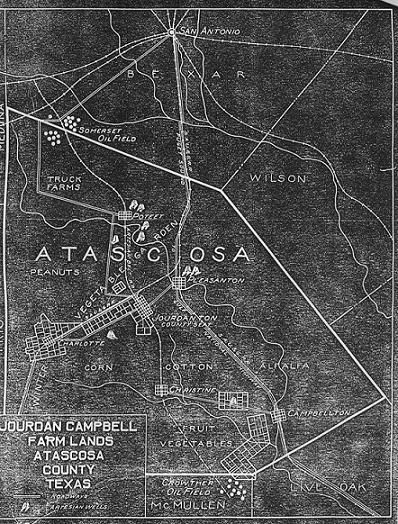

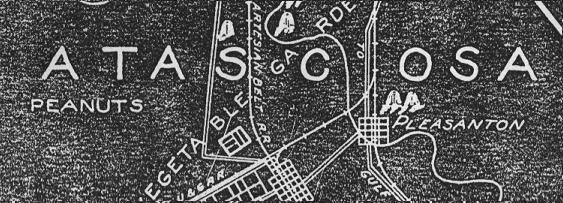

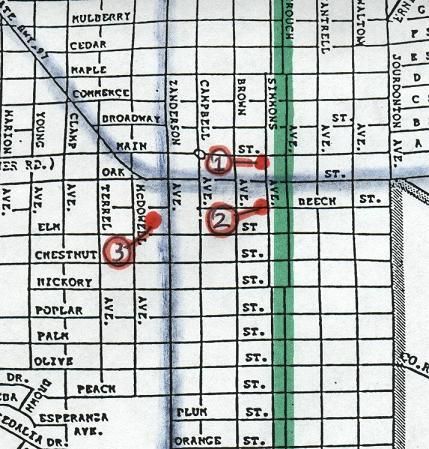

Artesian Belt map taken from the 1916 "OFFICIAL RAILWAY GUIDE"

Not being a man who lacked clarity of vision or the required resources to put ideas into effect, Simmons decided to build a railroad to his land. He had already made plans for a town to be called New Artesia which actually ended up being called Christine. Another town between Christine and Jourdanton was also created, called Imogene. However Mr. Porter has found reason to doubt why these towns were given these names. The accepted theory was that they were named after Simmons' daughters but historical records indicate that though he did indeed have daughters, these were not their names. Mr. Simmons was quite a character, who divorced his first wife only to marry her sister. His brother ended up taking him to court over business matters as well. The nearest main line to Christine was some forty miles to the north, in a roughly straight line that went near Poteet and Somerset. And so he set about acquiring right of way and materials and establishing a link at with the International & Great Northern line that ran from San Antonio to Laredo.

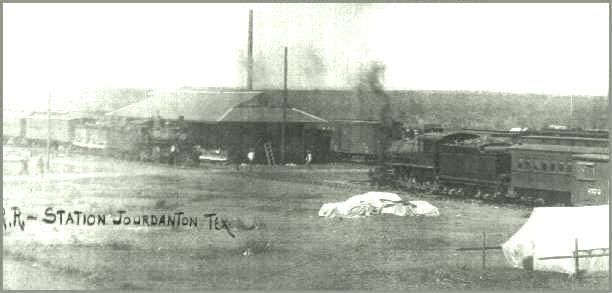

The new line was called the Artesian Belt Railroad in reference to the area's source of water, namely artesian wells. There is no obvious river in this area. The water is a few hundred feet underground. The intersection with the International & Great Northern was given the name of Kirk. There was no town at this place. Kirk may have been the name of an engineer or IGN officer. A depot was built to service interchange passengers, plus some sidings and freight buildings. Another spur was built another four miles north, allowing the new line to reach Macdona on the Galveston Harrisburg & San Antonio line. This was abandoned in 1920 as, by that time, the line was fully allied with the IGN.

While the new line was being built, Simmons went into overdrive, advertising his land all over the country as the "Garden spot of the world." By the time it was finished, the auctions to sell off the lots were thronged with buyers by the thousand. While many were dismayed by the true nature of the land and simply headed home, enough stayed for Simmons to make a huge profit on land sales alone, not to mention the revenue that would accrue from the railroad. Towns along the line began to thrive. Jourdanton was platted out as the railroad was being built and soon took over as county seat of Atascosa from Pleasanton after a vote to decide the issue. That Jourdanton was on the railroad and Pleasanton was not virtually decided the issue. With the construction, a few years later, of the San Antonio Uvalde & Gulf, Pleasanton did get railroad service and now, ironically, only it does. Poteet and Somerset also grew. Both towns relocated a few miles to be on the railroad, a common practice in those days. Railroad service, back then, could make or break your community.

Poteet was named after a blacksmith who had set up shop in the area and who would collect his neighbors mail when he went to town, causing the address to be written, "C/O Poteet." Farmers found that strawberries were very happy in the sandy soil of the area. Today it is still known as the Strawberry Capital of Texas. Refrigerated cars could whisk the perishable fruit into San Antonio and beyond. Other commercially viable products in the area were sand, coal and oil, all of which were in some abundance around Somerset.

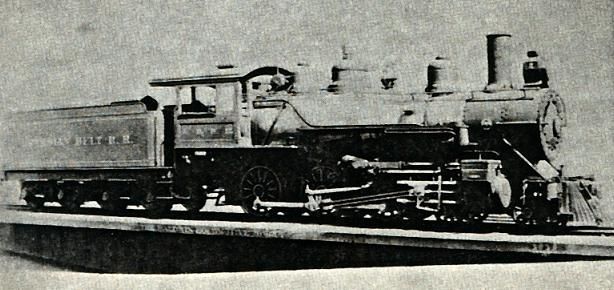

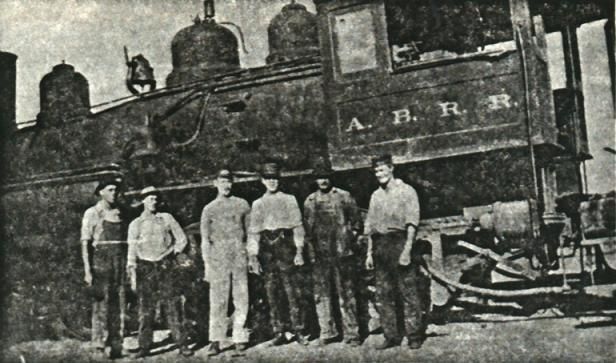

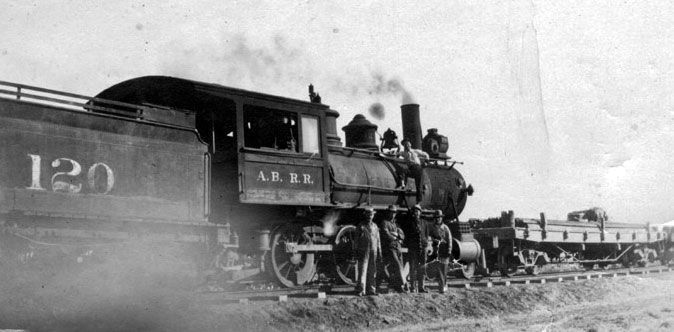

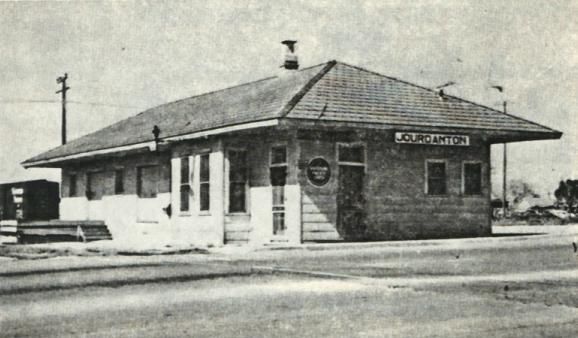

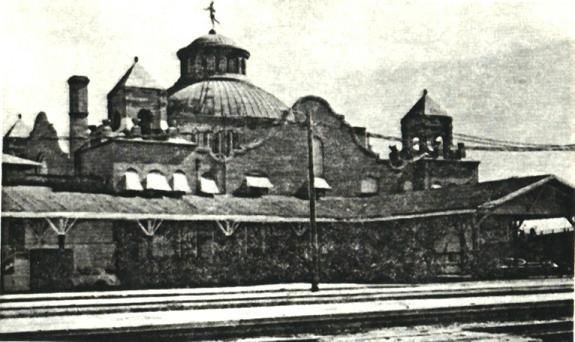

As the line had been privately financed it did not have any debts to be paid, not a luxury enjoyed by too many other roads. It used International & Great Northern line from Kirk into San Antonio, and its huge depot for passenger traffic. It was popular with everyone, especially children. One of the conductors, John Hoaker, would throw out candy to them as the train passed. It existed to serve a specific area, all of which was well served with water, easy to farm and rich in natural resources the rest of the world wanted. The company owned little in the way of rolling stock, which apart from three passenger cars and a couple of locomotives, it leased from the IGN. Further possibilities were created when the San Antonio Uvalde and Gulf was built from Crystal City to Pleasanton. The new line ran about one mile north of Jourdanton, with a spur into town. For 47 years Jourdanton had two railroads but, oddly enough, for most of the time, only one agent. Even before both railroads became part of the Missouri Pacific's "Gulf Coat Lines" division, it was expedient for both services to be served by only one agent. In 1920 this was a Mrs. Willoughby.

The lines biggest cost was maintenance of way. The land is prone to flooding, and the word Atascosa, the name of the county, means "boggy land that is difficult to cross" in Spanish. The land surface is liable to subside, and this would obviously create problems for the rails laid upon it. There were any number of derailments, but seldom were they severe in their consequences. One thing that mitigated this was the fact that none of the forty miles was crossed at high speed. Another was that after it rained the ground would be quite spongy so a softer landing of sorts would occur. There were no exclusive passenger trains on the line, except for an occasional special charter. Passenger coaches were placed at the end of mixed consists. As a result, even if the engine derailed, the coaches at the rear would most likely be unaffected except for some unceremonious reverberations due to the unexpected and rapid deceleration. Following an accident in 1909, the passenger cars stayed on the tracks and a borrowed Southern Pacific wrecker train was able to get the engine, #140, on lease from the IGN, back on the line the very next day. Repair to the line allowed normal business to resume at the same time.

The fortunes of the line changed in 1910. Dr. Simmons, who had come to Texas for health reasons, died. His entrepreneurial spirit did not fail him even up till the end. A new town was being discussed for the area in between Kirk and Macdona, to be called West San Antonio. It was highly speculative, to say the least, and with the passing of Simmons nothing came of it. The railroad would soldier on for the next ten years without strong leadership. The West Texas Bank and Trust Company of San Antonio were the executors of Simmons' estate and, as such, took over running the railroad. Stocks in the company were offered and the new stockholders met on February 2, 1911 to create a board of directors. A nine person board was created and P. McNemer was appointed as General Manager. Soon a new land and oil speculator called Hopkins emerged. He had purchased some vast tracts south of Christine and soon found both oil and gas in plentiful supply. When his approach to the railroad for an extension was rebuffed, he decided to buy it. However, he tried to sell lots on the land before the railroad extension was even planned and his plan fell through. In 1914, a major consortium, backed by English speculators, acquired the line. They intended to extend the line far, far to the south, not only to Rockport but further into the Rio Grande valley and into Mexico itself. This plan was quite close to success. Difficulties in providing sufficient local finance were all but overcome when the English backers decided, upon the urging of the mighty Santa Fe, to withdraw their support. The eruption of what became a World War did not help matters. Possession of the railroad reverted back to the West Texas Bank and Trust Company of San Antonio.

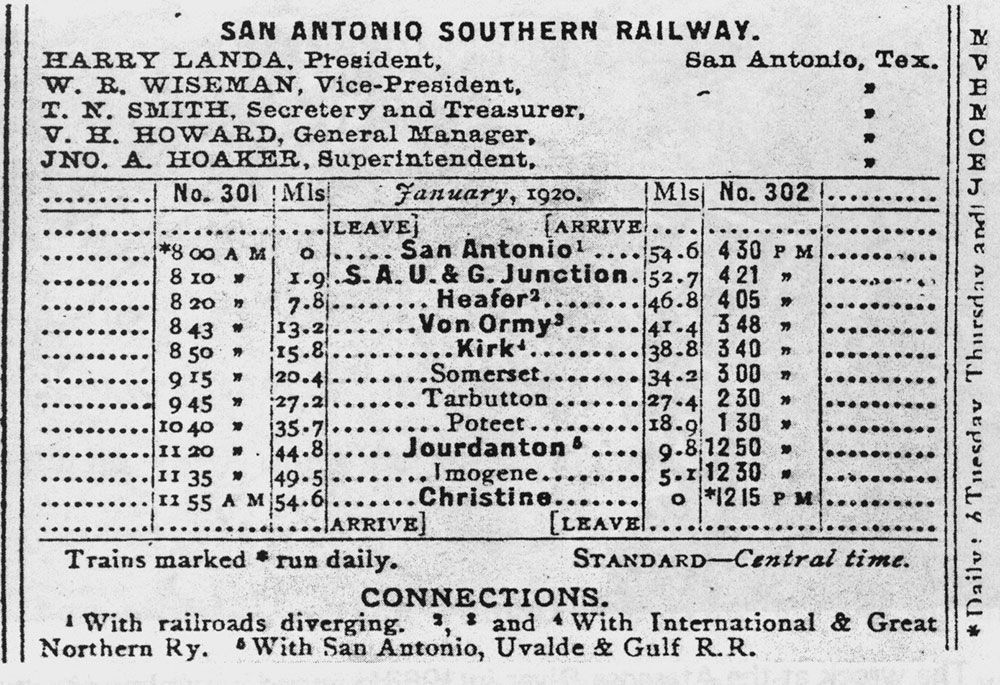

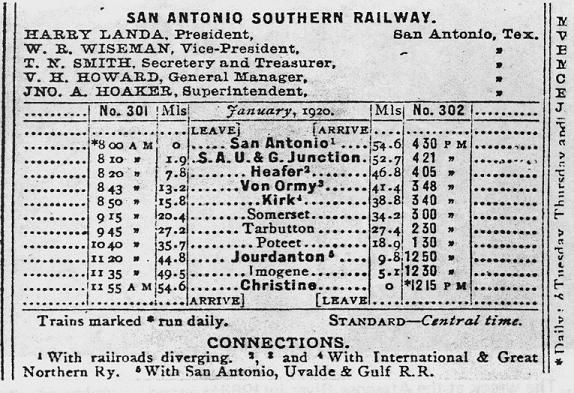

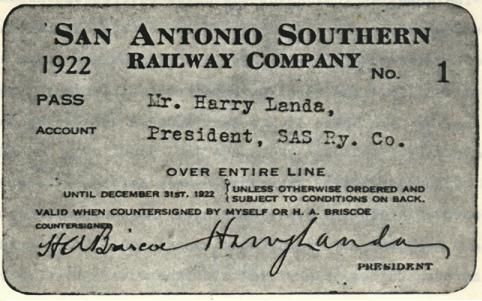

In 1916, the railroad gained a new president, Harry Landa, who just happened to be the president of the bank. The line had been allowed to decline by this time. It was taken over by the Federal Government in 1918, along with every other line in the country, following major problems with the industry's ability to support the war effort. By 1920, when control reverted back to the railroad companies, improved roads, cars and trucks had created tough competition for the movement of both people and freight, so when a willing buyer emerged, the bank was only too delighted to sell the line.

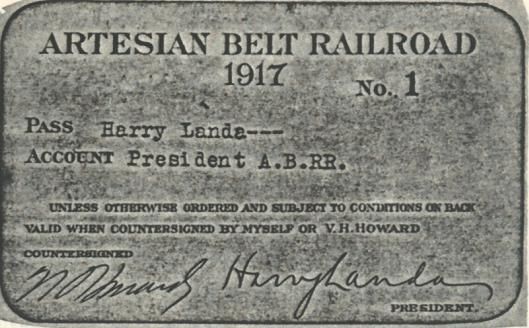

The new owner was Harry Landa, the president of the West Texas Bank and Trust Company of San Antonio. Like Simmons, Landa was also the son of a successful man. Joseph Landa had started off with just a grist mill in New Braunfels and ended up creating a substantial empire based around the Landa Milling Company. In due course, Harry took over the businesses but was drawn to banking in particular. He was, for a time the president of another San Antonio bank, the American Bank & Trust Company. When in 1915 it looked like the West Texas Bank And Trust Company was going to fail, he was approached by no less than the governor of the state of Texas. Harry owned a huge amount of stock in the bank. Governor Ferguson came to New Braunfels and made an offer no self respecting entrepreneur could refuse. Become the bank president and the state will deposit $1,000,000 in the bank. This money duly arrived and was put on display at the bank's offices on Alamo plaza. When Harry found the bank owned a railroad he decided to try to run it himself. His desire to buy it in 1920 came as a huge relief to the bank's bottom line. Harry had had no experience running a railroad and what he had found was hardly impressive to most people, namely a dilapidated short line that both started and ended, for all intents and purposes, nowhere.

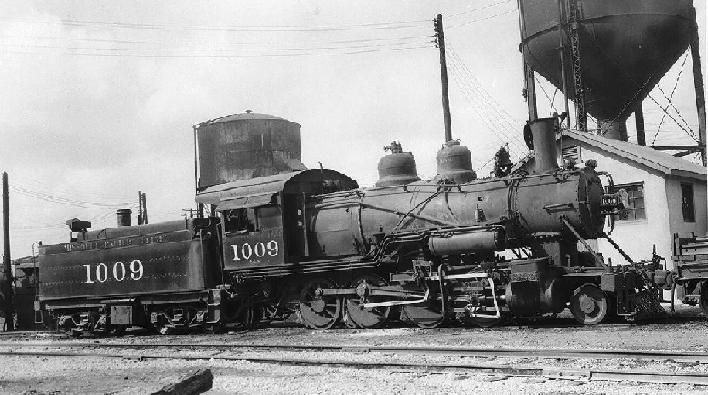

Following his purchase in 1920, Harry renamed the railroad the San Antonio Southern. He was the sole owner. He set about rejuvenating the line, to the extent of buying, straight out, a brand new locomotive while at the Baldwin factory in Philadelphia. He abandoned the line between Kirk and Macdona as the line was doing exclusive business with the IGN, including leasing its rolling stock. Landa was an astute business man. Baldwin was so surprised it would be paid in full he saved $5,000 off the agreed price of $40,000. He also had an asset that one can only imagine many a railroad wished it had, control of a well favored bank. Harry set about initiating loans and development money to farmers and businesses all along the line's 43 miles. He helped to create more cotton gins. He helped to get the San Antonio Coal company to re-open its mine. He helped the Slimp oil company build a refinery in Somerset. Sand pit operations were increased. The railroad served some 300,000 acres of which 250,000 was tillable and with new wells and equipment agricultural production was also increased. Within a short time, "Harry Land's Lemon," became the most profitable short line in Texas. The 1920 Texas Railroad Commission report of 1920 states the line had 43.21 miles of track, including sidings, between Kirk and Christine. In 1920, the S.A.U. & G. spur from its line one mile north of the town was removed, along with its depot.

Artesian Belt map taken from the 1916 "OFFICIAL RAILWAY GUIDE"

So profitable in fact, that in 1925 the Missouri Pacific offered to buy the operation for $600,000. Not bad, since Landa had only paid $250,000 for it just a few years earlier. When their offer was declined, they threatened to build their own line to Poteet. So Harry sold out, and the line was and, in due course, in 1927, the line became a part of the Missouri Pacific's Gulf Coast Lines, not the International & Great Northern, which had been fully acquired itself by the New Orleans Texas & Mexico, on behalf of Missouri Pacific in 1925. The San Antonio Uvalde and Gulf was acquired at around the same time. In 1933, the line between Jourdanton and Christine was abandoned, making a short line even shorter. The whole Missouri Pacific system went into receivership in 1933 from which it did not emerge until 1956. By this time the strict laws regarding the ownership of railroad lines in Texas had been relaxed, and the whole system was allowed to operate under just one name. It is doubtful that this had much effect on the San Antonio Southern, as it had not had any rolling stock of its own in decades and had, de facto, been just a small part of the larger system for many, many years.

Following a serious wreck on the line in 1963, the Missouri Pacific decided it could not justify the amount of money it would take to restore the line properly and the decision was made to terminate service and remove the rails. New roads and larger trucks had eaten away the line's essential function, plus many of the towns along the way were starting to steeply decline themselves, a process that was affecting small towns all across Texas. Some of the old depots were relocated and given a new function by their new owners, and many exist in a modified form to this day. Only the barest trace can be found of the old line today. The right of way was removed almost 40 years ago and its land has reverted to nature, been built on or plowed over. If you keep an eagle eye open on Highway 16, the route to Jourdanton, you can still see a small trace or two, some concrete blocks that raised the tracks or an abutment where the tracks were supported as they crossed small streams but there isn't much left at all. But in its day, it was the life creating artery that helped create a prosperous area and its passing cannot diminish its effects.

Christine today is a small community of around 100 inhabitants and only one business, a gas station and general store. It is hard to imagine thousands of people getting off the train here and so many buying land, but none the less it is what happened. The town had two hotels, a post office, a cafe and a general store plus a school which at one point had seven teachers and 175 students. The population peaked at 600 in 1914,when there were three cattle breeders plus purveyors of feed and lumber. It is doubtful that the old depot, which has not seen a train since 1933 is in its original location. It was donated to the town by a woman who was actually born within its walls and today it serves as a town hall and library.

February 2004

Sources: 1916 "Official railway Guide"

1920 Texas Railroad Commission Report

Rails To The Artesian Belt, by F.A. Schmidt, 1977. (Privately published)

Artesian Belt / San Antonio Southern Railroad Timeline

━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━

1908

Artesian Belt RR created by Charles Simmons to reach ranch land he was developing into farms in Atascosa County. It ran almost 35 miles south from the Southern Pacific tracks at Macdona on the western edge of San Antonio.

The town of Somerset relocates a few miles to be closer to the line.

━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━

1909

The town of Jourdanton is laid out on the route of the Artesian Belt building towards Christine. The town takes over as the County Seat the following year

━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━

1910

The town of Poteet relocates nearer the tracks.

Artesian Belt creator Charles Simmons dies. Control of the railroad passes first to family members.

━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━

1911

Flowing land auctions that attracted people from as far away as Europe, the town of Christine created as the terminus of the Artesian Belt by Simmons has a post office, two hotels, a cafe and a school with 141 students.

━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━

1912

Tracks between Fowlerton and Pleasanton belonging to the San Antonio, Uvalde and Gulf intersect with the SAS just north of Jourdanton. A spur line to serve a downtown depot is built.

━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━

1914

English capitalists purchase the line with a view to extending it but these plans fall through with the onset of World War One. A bank becomes the new owner of the line.

━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━

1916

New bank president Harry Landa of New Braunfels takes an interest in the railroad and begins offering loans to businesses, farms and ranches along its route that greatly increase its freight traffic and its profitability

━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━

1918

The line is nationalized, as are all US railroads, in an attempt to fix wartime transportation difficulties

━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━

1920

Bank president Harry Landa buys the railroad and re-names it the San Antonio Southern. He continues to help develop the local area, resulting in the SAS becoming one of the most profitable lines in Texas, short line status notwithstanding.

The connection with the Southern Pacific tracks near Macdona is abandoned, leaving the line connected with the Missouri Pacific at a site called Kirk.

━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━

1925

Landa rebuffs offer form Missouri Pacific to but the line. MOPAC threatens to build a parallel line to access oil wells and other industries.

━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━

1927

The Missouri Pacific acquires the San Antonio Southern

━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━

1933

Ten miles of tracks to Christine are abandoned, making Jourdanton the new terminus of the line. The depot is relocated to the north side of Highway 97

━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━

1942

A major oil discovery just outside Jourdanton leads to a large yard to handle tanker cars being built just north of the town.

━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━

1963

MOPAC abandons the line which had only been used in recent years as a dumping ground fro passenger train trash, according to locals.

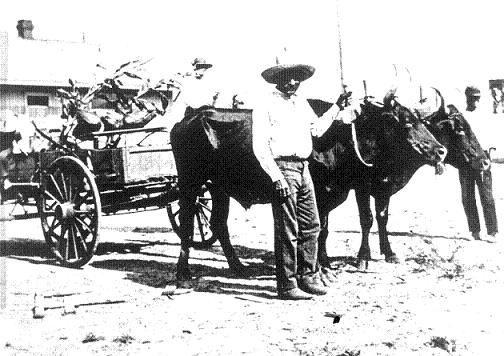

Frank Crothers at the San Antonio bicycle race track.

Transportation Museum

CONTACT US TODAY

Phone:

210-490-3554 (Only on Weekends)

Email:

info@txtm.org

Physical Address

11731 Wetmore Rd.

San Antonio TX 78247

Please Contact Us for Our Mailing Address

All Rights Reserved | Texas Transportation Museum