San Antonio, Fredericksburg and Northern Railroad /

Fredericksburg and Northern Railroad

Introduction: Getting to Fredericksburg Before the Railroad

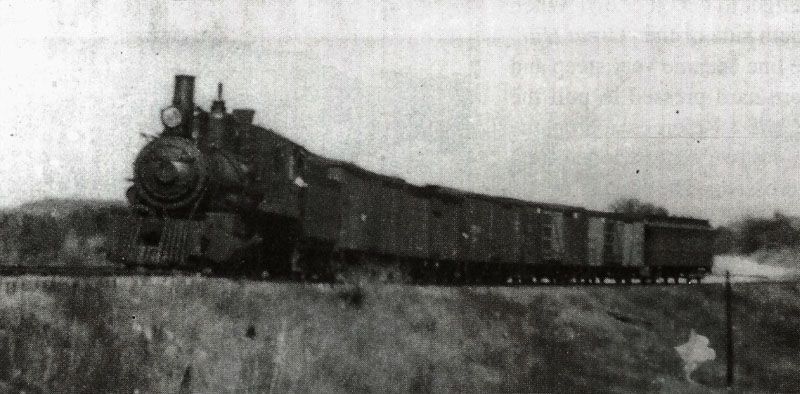

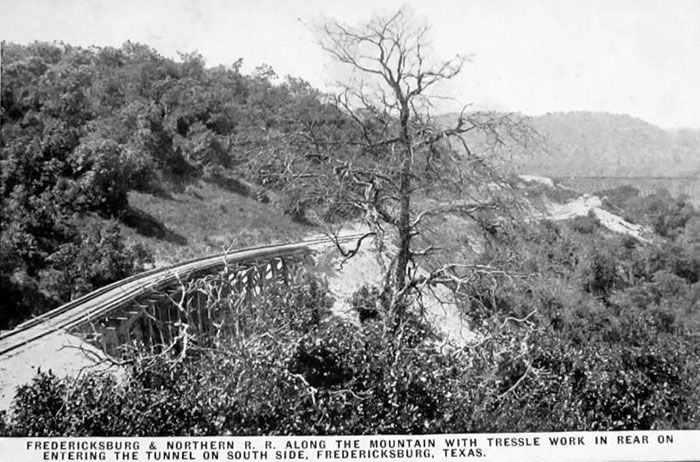

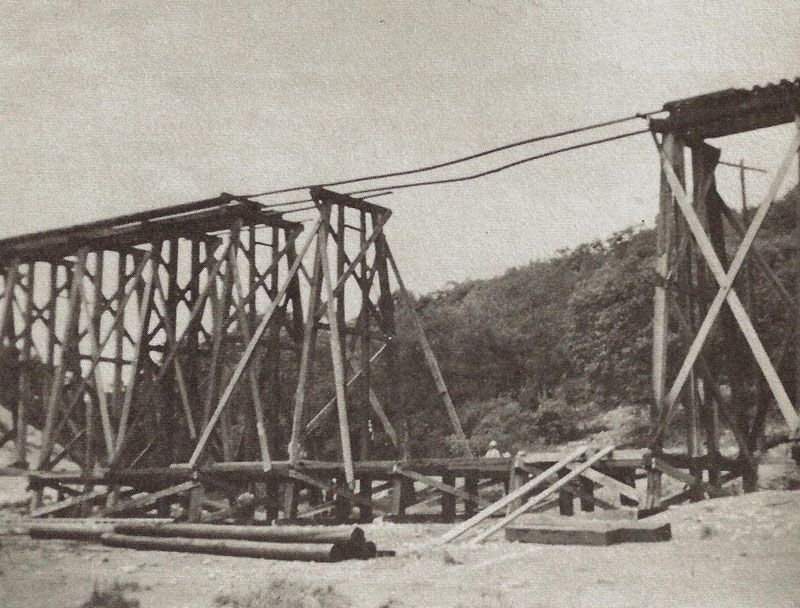

The story of the San Antonio, Fredericksburg and Northern Railroad is one of optimism and dogged determination. Citizens in Fredericksburg struggled for twenty-five years to establish a railroad connection to their city, which was located in a geographical area far from ideal for railroad operations. Opened in 1913, it was one of the last lines built in the region. There was a need for it at first but it never managed to boost the economy and production as was hoped. Lacking a year round bulk shipment customer, it was also quickly overtaken by other transportation developments. Its construction involved building twenty-four bridges, one per mile, ranging in size from twenty five to seven hundred forty three feet, and the digging of a tunnel nine hundred twenty feet long, one of only six railroad tunnels built in Texas. After almost three decades of only marginal profitability at best, service ended in 1942. Few traces of its right of way remain today. Its best known remnant is the tunnel which is now home to millions of bats.

The need for a railroad is best illustrated with a few historical facts about how difficult it once was to reach Fredericksburg. The town was first settled in 1846 by a group of German men, women and children numbering one hundred and twenty. Having crossed the ocean and arrived in Texas at Indianola, they had first made their way to New Braunfels, most likely on foot. From there, it took them sixteen days, using only small hand carts, to complete the last eighty-five mile leg of their journey. Larger ox pulled wagons were not available because the United States army, which had only arrived in Texas a few months earlier, was preparing for the war with Mexico and any available large wagons were being used for this purpose.

As Fredericksburg began to grow and primitive trails were improved, it still took an ox drawn wagon ten days to travel the seventy-five miles of bad roads to San Antonio. The twenty-five miles to modern day Waring, were the worst. The poor beats had to haul freight both up and down an additional three hundred feet of elevation above sea level, over rocky trails and fording streams that could quickly swell after the slightest rainfall. These trails were gradually improved which allowed the use of mules and horses and buggies for personal transportation and the mail. By the time the railroad began inching its way into the Hill Country, it only took the mule drawn stage coach two days to get from Fredericksburg to San Antonio, with an overnight stop in Boerne.

Fredericksburg Bypassed by the SA & AP in 1887

The construction of the San Antonio and Aransas Pass Railroad between San Antonio and Kerrville in 1887 was both a blessing and a curse. The residents of Fredericksburg has petitioned the railroad's engineer, Uriah Lott, to consider building tracks to their community but Kerrville was chosen for both financial and topographical reasons. They offered more money and the terrain was more conducive to operating trains, which do not do well on even the mildest grades. While railroads benefit from reduced friction, this does not allow for the easy ascent of hills, which presented themselves in abundance all the way to Fredericksburg. The small community of Waring was the nearest railroad depot to Fredericksburg. It could take the best part of a day to travel the twenty-five mile distance over still quite primitive roads.

That same year the the SA & AP bypassed Fredericksburg, 1887, a banker by the name of Temple Smith from Virginia moved into the town and set up the Bank of Fredericksburg. He also formed a railroad committee with other prominent citizens. Despite the many obvious obstacles, they did not give up. It took them twenty five years to achieve their goal but they were able to facilitate the construction of a railroad in 1913. There were over thirty plans made during this time. A few were more serious than most, leading to several miles of graded road bed for tracks that never came. 1889 saw the most ambitious yet ultimately unsuccessful attempt when seventeen miles were graded from near Comfort, at a cost of $85,000. (And none of it was used in the line that finally was built.) The city's hopes were raised then dashed again in 1901 when the St. Louis and San Francisco Railroad, better known as the Frisco, announced its intentions to build towards Fredericksburg from the north, but the tracks came to an end in Brady instead. Yet another attempt began some grading work in 1909 before funds ran out. Smith went back to visit bankers in the north, many of whom he knew personally, but he was unable to obtain what would today be called venture capital.

Construction Begins in Earnest

The main individual who made the much hoped for railroad a reality was a construction engineer by the name of Foster Crane, who recently completed the Medina Dam in part by building a temporary railroad from the Southern Pacific tracks at Dunlay in Medina County, west of San Antonio, on the way to Hondo. With Crane in charge of construction, work began with just enough money raised by popular subscription in Fredericksburg and smaller communities and land owners along the proposed route who stood to benefit from its construction. Further funds were promised by the Chamber of Commerce in San Antonio.

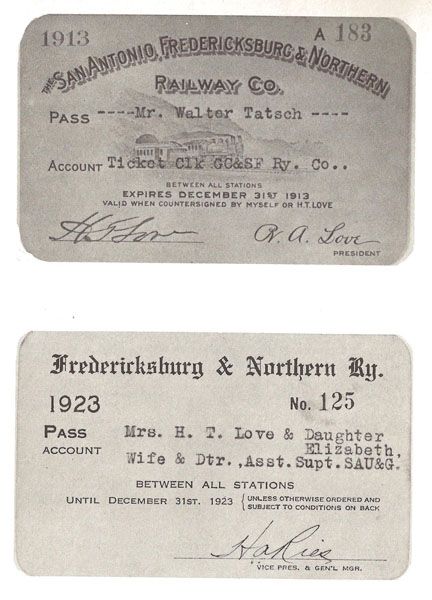

The San Antonio Fredericksburg & Northern connected with the main SA & AP line between Waring and Comfort. As Uriah Lott of the 'SAP' had realized many years before, building in the hilly terrain caused staggering construction difficulties.. Costs soared over the original estimates and created problems that would bedevil the line for its entire twenty-nine year existence. When service began in 1913, the SAF & N failed financially almost immediately, due to the enormous construction debts. The railroad was run by a receiver until the end of 1917 when it was reorganized as the Fredericksburg & Northern Railroad. Its main creditor in 1913 was the construction engineer, Foster Crane, whose contract stipulated that he be responsible for all debts until he was paid when service began. The total collected did not even match the amounts promised, let alone the additional expenditures.

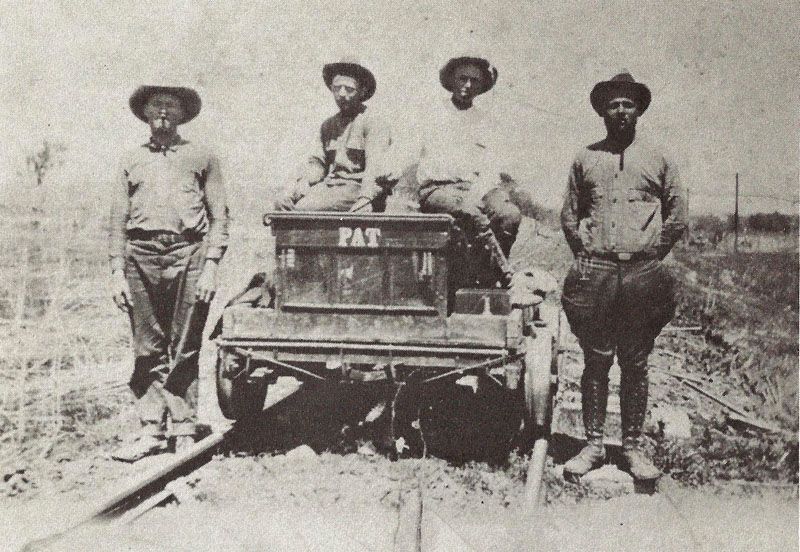

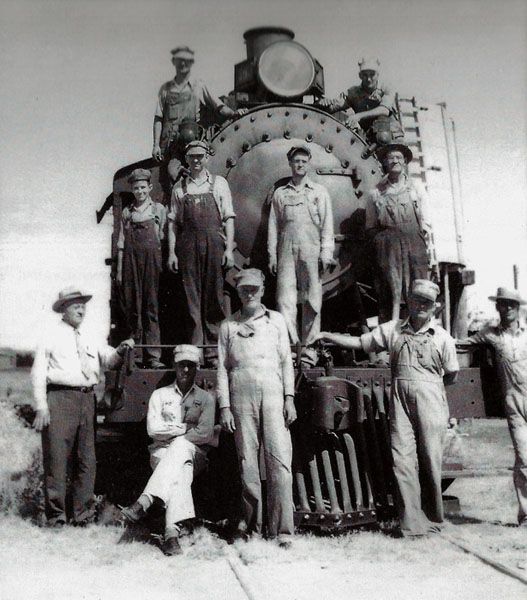

The project required the hiring of around two hundred and fifty men. At fifty cents a day, the twelve hours a day, six days a week job attracted mainly Black and Hispanics laborers. One of the many construction delays was caused by a mass desertion of manpower during the harvest season. While working on the railroad the men were quartered in a tent city that was moved to keep pace with construction. Whether or not the men had to pay for their food from their pay is not known, but when the commissary was robbed it was relieved of $60 in coins only - the thieves ignored, either by accident or design, a larger amount of paper money in the facility. The project also required up to 100 teams of oxen, mules and horses. Their owners were paid $2 a day for the use of the animals but this did not include food, water and stables.

To build a sufficiently level grade that would scale the three hundred feet elevation as gently as possible, the workers, using mainly hand operated tools and wheel barrows, had to move a phenomenal amount of material. Some was hauled in by train to Waring. More was created by making cuts for the tracks through many hills and using the "spoil" to fill in low lying areas. When it was finally decided it would be impossible to go around the highest point on the route, a place known as "The Big Hill," the resulting 920 feet tunnel provided a vast quantity of hard limestone for use on the line. It was blasted out with dynamite placed in holes bored by hand operated drills. It was dug out from both ends in three tiers at once, each progressing at the same pace, to avoid the use of costly scaffolding. The tunnel was never internally braced. This obliged trains crews to stop the train before entering to check for large rocks on the tracks. Regular passengers soon became used to a steady patter of rocks on the roof of the passenger car as the trains slowly chugged its way through, with windows closed to keep out the smoke.

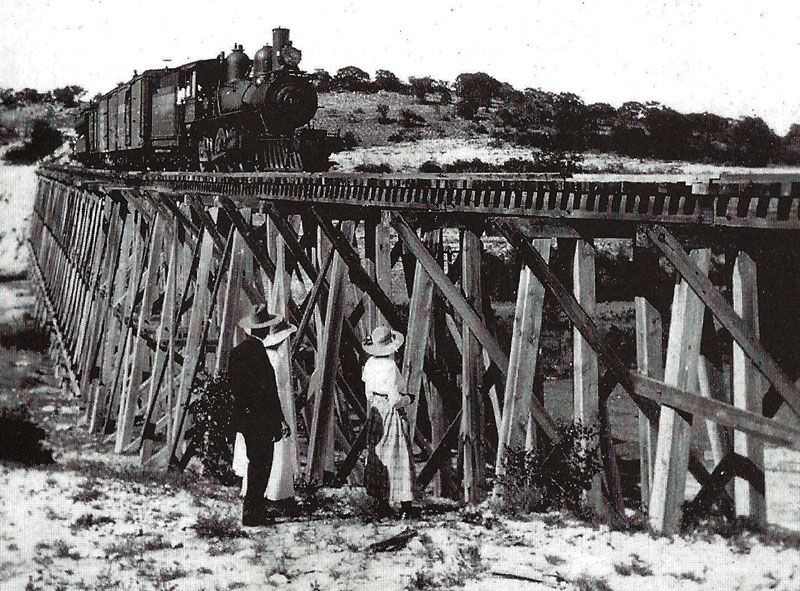

The twenty-four mile of tracks required twenty-four trestles and bridges ranging in length from twenty-five feet to seven hundred and forty, the largest being almost forty-two feet high, under which the unpaved road, now known as the "Old San Antonio Road" was routed. The largest gap between bridges was only two miles. In other places, the train went immediately from one trestle to the next. The rails coped with numerous additional water courses with fill dirt and water pipes. While construction of all these structures was difficult and expensive, maintaining them would be a constant headache for the twelve person track maintenance crew. Posts on the bridges split, became loose or fell off. The fill dirt settled unevenly, causing the tracks to sink or sag on one side only. Keeping the line in operating condition would always be a huge drain on the company's budget, as indeed would be the time, money and effort required to re-rail the train, sometimes multiple times on just one trip.

After 33 Years of Anticipation, Rail Service Comes to Fredericksburg

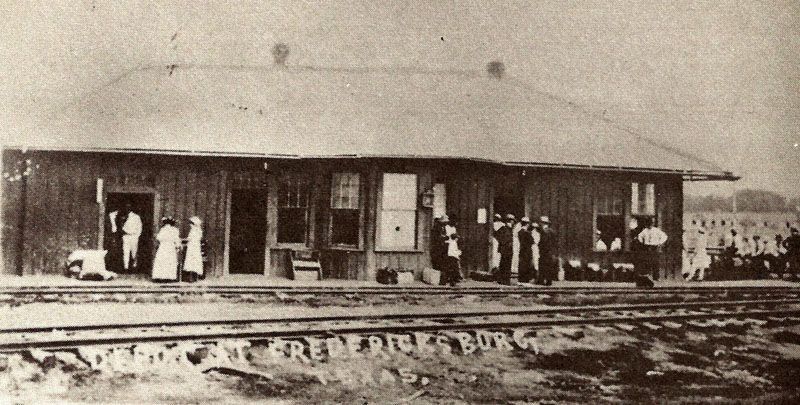

The first survey regarding bringing a railroad to Fredericksburg, Texas was conducted in 1880 by Palmer and Sullivan. The San Antonio and Aransas Pass Railroad declined to build there in 1887. Thirty more attempts, some more serious than others, took place but finally, on October 27, 1913, a seam train entered the town, carrying construction materials to finish the tracks and to build a platform and depot. In eager anticipation, a load of cotton awaited its return to Fredericksburg Junction, just north of the Guadalupe River railroad bridge, nearer to Comfort than Waring. Lacking anything better, they were left on the ground and transported on open flat cars. This caused considerable damage to the shipment and much of it was lost. Other railroads had already learned to keep the hay bales off the ground to prevent rotting and that the cars carrying them should be placed ahead of the locomotive to reduce the impact of oily smoke and sparks. Such was the level of competence at the outset. Stories abound of the steam locomotive and the tender setting out without sufficient water, a situation that could have the most explosive consequences, and of the very earliest locomotives running out of coal, causing the crew to cut down trees to maintain boiler pressure. Some of these tales strike this author as exaggerations, especially as by 1913 almost all steam engines, even the used ones that the SA &FN could afford, were oil fired, but nonetheless they just might be some truth in them.

What is true is that the grand celebrations to mark the beginning of railroad service were fraught with difficulties. The date was pushed back again and again. When the time finally came, it rained so hard that the meat purchased for the planned barbecue had to be sold uncooked. At the same time, when they were approached regarding the lease of several Pullman coaches for a special train, the Missouri, Kansas & Texas Railroad said no to the San Antonio Chamber of Commerce, having assessed the line as too risky for such valuable rolling stock. While a freight car might be relatively undamaged if it tumbled down an embankment, the same could not be said for a passenger car or its "cargo." In the end they relented but there concerns were proved entirely valid. The train bringing them in for the big day on November 18, 1913, was over three hours late due to a significant amount of road bed subsidence caused by the heavy rain. It was also apparent that the first locomotive owned by the SAF &N was not strong enough to make the grades when pulling a heavy load and a siding near the tunnel had to be used to split the train, causing even greater delays in the already "elastic" timetable.

SAF&N Enters Receivership Within a Year

Despite the movement of some marble mined near to Fredericksburg itself, there was insufficient freight to make the line profitable. Ranch and farm produce is seasonal by nature, and the railroad struggled to make ends meet. The revenue projections proved to be hopelessly optimistic. Greatly compounding the financial difficulties the new railroad found itself in was that the construction costs had been woefully under estimated to an even greater extent. The tunnel was not even in the original budget. At $134,000, it alone increased the original assessment of $200,000 by 67%. Foster Crane, the construction engineer, found himself in an impossible situation. He had borrowed heavily to pay for project, under the terms of his contract, whereby he was personally responsible for all costs, obviously with the expectation of not only being reimbursed but paid a bonus. He had no choice but to sue the backers of the project. They in turn placed the railroad in receivership, less than a year after it began operations, in the hope of finding a buyer willing to pay a premium for the now functioning railroad, and create financial stability. None came forward. All the original investors and, of course, Mr. Crane, lost out on the deal quite badly.

While the SAF&N languished in receivership, safe from its creditors, others dreamed of extending its tracks to the north, thus bringing in more revenue and fulfilling the "Northern" part of its name. Crane himself was a party to these schemes, with a modest proposal to extend the tracks six miles to the granite quarries in the area, declaring he would rock ballast the entire existing line into the bargain, resolving much of the subsidence problem, Others dreamed of links to the Frisco at Brady, or an extension to Mason, and even, once again, a line all the way to the Santa Fe Railroad in San Angelo, the original aiming point for the San Antonio and Aransas Pass, twenty-seven years earlier. While hope springs eternal, none of these plans came to fruition, though some miles of grade work was actually started at one point. In the end the SAF&N was purchased for $80,000 by a group of Fredericksburg and San Antonio businessmen, who negotiated a reduced debt load as part of the deal and renamed the company the "Fredericksburg & Northern."

A look at their 1920 balance sheet as presented to the Texas Railroad Commission reveals a railroad struggling to survive under a debt load it simply could not pay off. The company made a miniscule operating profit of just $148. It earned a total of $60,817 over expenses of $60, 669. (It made a profit of $15,354 in 1919 from revenue of $50,381 over expenses of $35,027.) It transported 5,115 passengers, an average of fourteen per train, which brought in a total of $6,744. Carrying the mail brought in $1,132. The bulk of its cash flow, as with any railroad, came from freight. What is most telling here is that the largest single item was actually "LCL" or less than car load freight. The lack of year round bulk freight was a problem this line could never overcome. The second highest commodity was the movement of the "products of agriculture," such as fruits, vegetables, wheat and corn, which, as previously stated, are seasonal at best. The railroad employed 29 people of which the largest group was the 12 person track and bridge maintenance crew. It owned one locomotive and one passenger car. It leased all the freights cars in service. It spent $5,334 maintaining its rolling stock which was only worth $4,110, and $16,080 on maintenance of way. Its fuel cost $15,976. Altogether, the F&N had a total valuation of $127,335 and liabilities of $287,945. The accrued interest alone came to $9,041.

A Ray of Hope, Hubris and Disaster

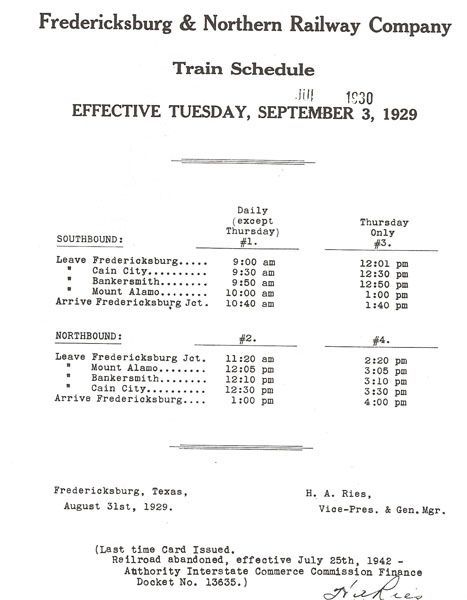

There was a glimmer of hope in 1929 when Texaco and Humble Oil built a series of pipe lines around the country to expedite delivery of oil – and reduce railroad shipping costs. F&N executives approached the pipe line contractors and negotiated a mutually acceptable deal whereby the route through the Hill Country came close to Fredericksburg putting the F&N well placed rate to move pipes and other material close to the work areas. For a time, the F&N ran two trains a day, even extending the end of the line across Highway 16 into an open lot to improve access for trucks hauling the material to its final destination. At the same time the railroad retired its venerable 52 seat wooden sided passenger car and replaced it with a a twenty seat passenger /light freight combination car, which was, in fact, the only freight car the railroad ever owned outright. After many years of sitting idly, the original passenger car was stripped to its frame in 1936 and converted to accommodate a pile driver to assist with bridge repairs.

In 1929, just as the F&N was doing the best business in its history, its owners missed the only opportunity they would ever get to sell the entire railroad to the Southern Pacific. A very serious and well-funded attempt to build a rail line from Fredericksburg to San Angelo by a wealthy San Antonio businessman called R.W. Morrison came crashing down with the stock market. He offered his charter for the proposed "Gulf and West Texas Railway Company" to the Southern Pacific who were interested providing they could make suitable arrangements with the Fredericksburg and Northern. The owners said that the SP would have to buy the F&N outright, to which again the SP said yes to, but only for its appraised value of $227,000, established by the Interstate Commerce Commission. In a decision they would soon come to regret, the owners held out for at least $350,000, and the SP walked away from both deals. Three years later, at the very depths of the Great Depression, the F&N offered itself, cap in hand, to the SP on presumably more favorable terms to the railroad giant, but they did not even bother to respond, despite pleas from many prominent Fredericksburg office holders and residents.

As the Great Depression raged, things got worse but, somehow, service continued. Even as roads and the vehicles that used them improved, rail bridges washed out. They were rebuilt. The road bed compacted. It was built back up. Trains derailed constantly and were re-railed with practiced ease. While the passenger car at the end of the daily mixed train seems to have stayed upright on or near the tracks, it seems that a lot of freight cars were not so lucky. It's a sad commentary upon a railroad with so many track difficulties, but the SAF &N and the successor F&N was not only unable to acquire a rail wrecker to re-right the freight cars and put them back on the tracks, it could not even afford to rent one from the Southern Pacific when needed. Instead it relied on human strength and ingenuity, using rope, chain, block and tackle attached to the locomotive to rescue these cars and their contents sometimes from quite steep ravines. Miraculously the F&N did not report a single accident resulting in injury or death for the entire year of 1920 and as passenger numbers continued to decline, this fortuitous record continued.

The worst incident in the history of the F&N happened in the early 1930s when a track gang was returning from fixing one of the twenty-four bridges along the route. A tool slung under their motor-car came loose causing an abrupt halt. One of the crew who fell off was struck by another heavy tool from the small flat car being towed by the motor-car and killed. In another notable incident in 1936, a bridge collapsed after heavy rain just after the train crossed it on its way down to Fredericksburg Junction. Then a bridge ahead of it was swept away by a raging torrent, isolating the train for almost a week, though its crew and a few passengers were removed much sooner. Arson was suspected in a fire that took out a large section of the largest bridge on the route. Drivers on the road that went under the span reported seeing men bundling wood around some bridge supports. In response to this and other acts of vandalism, the railroad, with the blessing of the county judge offered a most Texas resolution that brought these outrages to a swift end. $5,000 was offered for the capture of any living miscreants, and $10,000 for any dead ones.

Decline of Passenger Service and Ultimately, The Entire Railroad

In the early days of the railroad, a person departing Fredericksburg by train at 5:40 AM on a Monday, Wednesday or Friday might reasonably expect to be at the San Antonio and Aransas Pass depot in San Antonio by 12:00 noon. On Tuesday, Thursday and Saturday, the trip took slightly longer. Beginning at 12:00 a traveler would not be at the SAP station until 7:00 PM. There was a similar variance on the way back, only this time it was faster on the second rotation. Sundays were different again. This day was set up to accommodate day trippers and was probably the busiest day of the week for passengers. Nonetheless, this was a remarkable improvement over the two day ordeal by stage coach and the ticket price was much more reasonable. In a quirk of history, as competition from buses increased, passenger service by rail got worse. Persons wishing to go to San Antonio were obliged to wait for four hours at the depot at Fredericksburg Junction, which was located in the middle of nowhere, without such niceties as air-conditioning. The train from Fredericksburg would meet with the northbound SP train to Kerrville at the junction and transfer any passengers, mail and light freight intended for that destination. It and passengers aiming for San Antonio then waited for it to come back where, once again, mail, light freight and passengers for Fredericksburg would move from one train to the other. Only then could passengers going to San Antonio from Fredericksburg make further progress towards their destination.

By comparison, there were several buses a day going to both Kerrville and San Antonio. In its 1942 request to the Interstate Commerce Commission to abandon service entirely, the F&N reported carrying thirty-six passengers in 1940 and only 3 in 1941. It had not a profit in ten years. It lost $12,775 in 1939, $17,248 in 1940 and $4,125 in 1941. When its only locomotive, #11, purchase second hand in 1921, was damaged beyond repair by ice in the tunnel in December 1936, the company was unable to replace it and had to rely on whatever motive power the SP would provide, and as the war progressed, even this cost was becoming unmanageable. Most damning of all, its main bank note of almost $250,000 had come due on 12/28/1941, with absolutely no means to repay or extend it further. With war work expanding, there was a pressing need for rails and other track materials at rapidly expanding military bases around the country while, at the same time, Fredericksburg had no military related industries or activities. The ICC had no choice but to accept the application to abandon the line.

The bank was keen to minimize its losses and took an offer of $77,050 from a rail salvage company over a hastily put together offer of $60,000 from a group of Fredericksburg citizens making a last ditch effort to save the line. Within a week of the last train leaving Fredericksburg on July 29, 1942, crews began pulling up the tracks and dismantling the bridges and trestles. Within two months only a few buildings, including the depot in Fredericksburg, and the tunnel remained. All the steel was purchased by the War Production Board. Most of it was re-used to assist in improving war transportation in the USA but a certain amount was sent to Australia, where there was an equal shortage of rails. None went to Japan, not a stick of it, contrary to a popular myth, which says that US Marines found rail marked SAF&N in Japanese fortifications across the Pacific. This nasty little lie ignores the fact that the tracks were pulled up seven months after Pearl Harbor was attacked, and that rails, produced in foundries in places such as Pennsylvania, have never been stamped with the names of any particular railroad.

Conclusion

There is an enduring fascination with "Rails to the Hill Country." Both the lines to Kerrville and Fredericksburg live on in the minds of both rail enthusiasts and casual observers alike. That neither ever made a profit seems somehow to give them a valiant underdog status that is denied to more workaday lines built by larger railroads. What is undeniably true is that these tracks went through some of the most handsome real estate in Texas. Both might do quite well as tourist lines if somehow the old right of ways could be resurrected. That this is economically impossible only seems to add to the lure of these old railways which passed into history so long ago. A surprising number of depots still stand and, if you know where and how to look, traces of the old right of way can still be found. The old tunnel has become a tourist attraction in its own right. People flock to it as night falls to see the millions of bats which have made it their home fly out en masse in the most spectacular fashion. And as impressive as this is, there are a good number of visitors who would much rather be waiting for a steam train to fill the sky with its sounds and smoke once again.

San Antonio Fredericksburg and Northern Railroad Timeline

━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━

1880

The first railroad survey of the Hill Country is made

━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━

1887

The San Antonio and Aransas Pass begins rail service to Kerrville, bypassing Fredericksburg

━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━

1887 - 1912

No less than 30 plans are floated to build a railroad to Fredericksburg. Some even get as far as building some miles of graded track bed.

━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━

1913

The San Antonio, Fredericksburg and Northern Railroad begins service from Fredericksburg Junction between Waring and Fredericksburg. 24 miles long, the route climbs over 300 feet and required 24 bridges and one tunnel

━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━

1914

Crippling by higher than expected construction costs and lower than expected revenue, the SAF&N is forced into receivership - one step shy of declaring bankruptcy

━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━

1917

The railroad emerges from receivership with new owners and a new name, the Fredericksburg and Northern Railroad

━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━

1919

The F&N makes an operating profit of $15,354 from revenues of $50,381

━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━

1920

The F&N makes an operating profit of $148 from revenues of $60,817

━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━

1929

The F&N carries pipe and other material for an oil line being built through the Hill Country

The Southern Pacific, in conjunction with a proposal to extend the line to San Angelo, agrees to but the F&N for its assessed value by the Interstate Commerce Commission of $227,000. The share holders hold out for $350,000. The SP walks away from both deals.

━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━

1932

The F&N's approach to sell itself to the SP is ignored by the railroad giant

━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━

1936

Heavy rains wash out several bridges. Suspected arson damages another. The F&N's only locomotive is damaged beyond repair by ice in the tunnel. The F&N is obliged to lease replacements from the Southern Pacific due to an inability to buy a replacement

━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━

1939

The F&N makes an operating loss of $12,775

━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━

1940

The F&N makes an operating loss of $17,248

━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━

1941

The F&N makes an operating loss of $4,125

━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━

1942

The F&N's application to abandon service is accepted by the Interstate Commerce Commission. The railroad had not made a profit in ten years. Its tracks and other materials are quickly pulled up, sold to the War Production Board and used to facilitate the increased need for tracks in other areas of the country.

Transportation Museum

CONTACT US TODAY

Phone:

210-490-3554 (Only on Weekends)

Email:

info@txtm.org

Physical Address

11731 Wetmore Rd.

San Antonio TX 78247

Please Contact Us for Our Mailing Address

All Rights Reserved | Texas Transportation Museum