Missouri Pacific Railroad in San Antonio

Page One

We wish to thank to the Generations Federal Credit Union, formerly known as "San Antonio City Employees Federal Credit Union" and in particular, it's president, Mr. Tim Haegelin. They were most gracious and allowed almost unlimited access to their treasure trove of material about the former depot and their restoration effort.

We are further obligated to both the Institute of Texan Cultures and the San Antonio Conservation Society. Both of this incredible organizations perform a fantastic job maintaining unsurpassed archives of the life and times of this glorious and multi-faceted city.

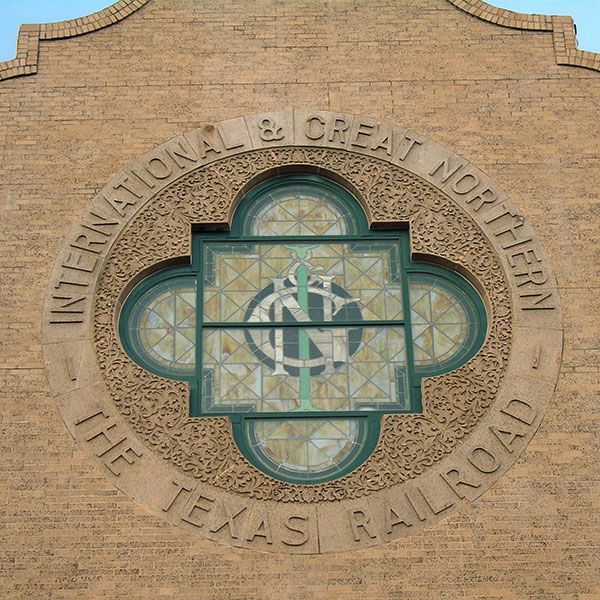

Early Days - The International and Great Northern Railroad

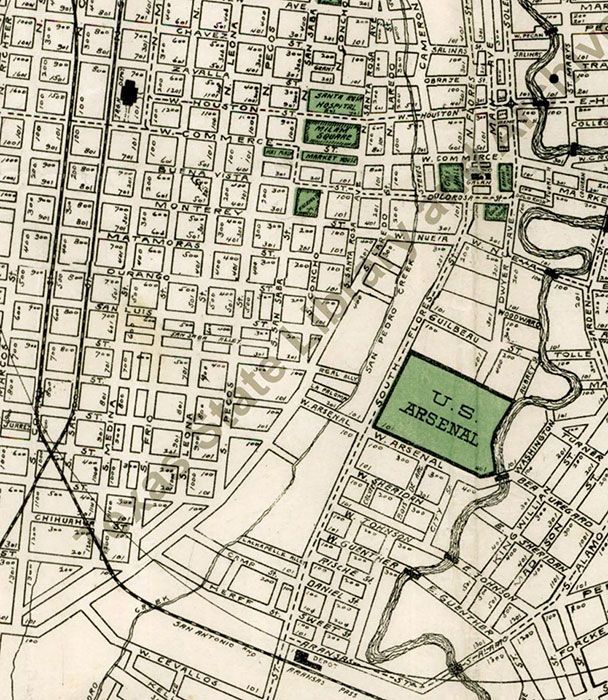

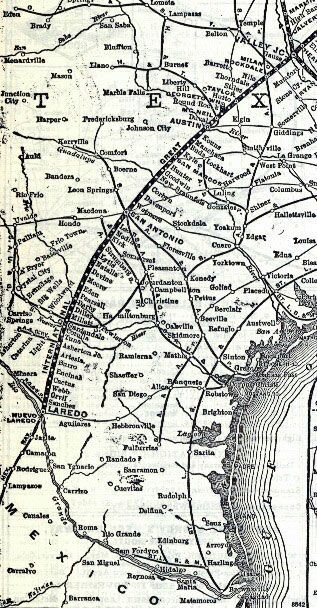

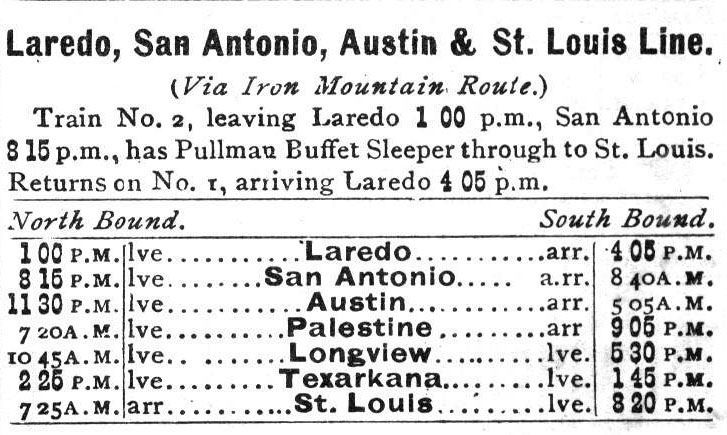

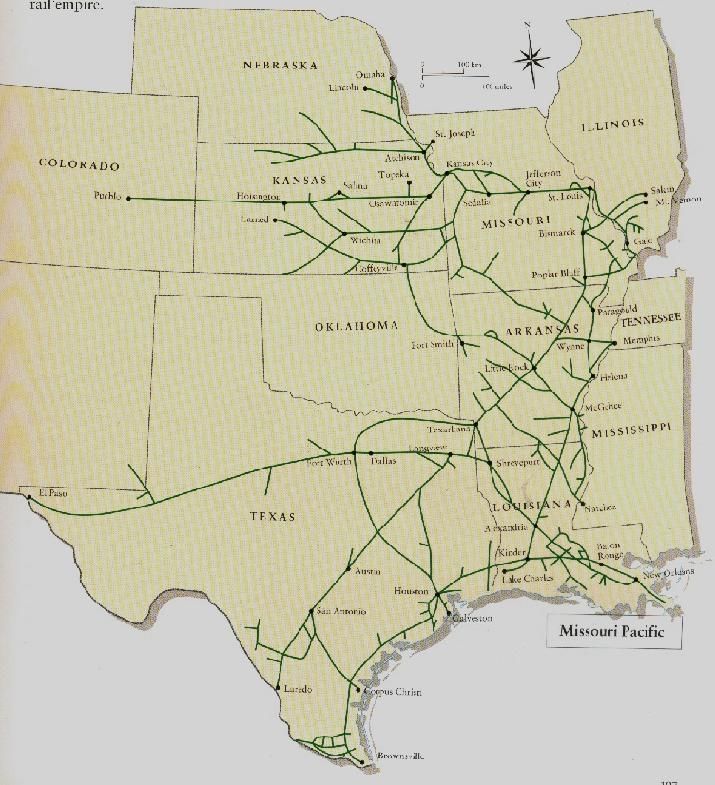

San Antonio gained a second railroad connection in 1881 with the arrival of the International and Great Northern. This line provided two very important links. It ran north to Longview, Texas, where it connected with other elements of the Missouri Pacific, providing the city with a vital link to the rest of the country. It ran south west to Laredo, and the lucrative trade with Mexico. With the Southern Pacific running east to Houston and west to California, San Antonio became a central point for trade in all directions and the city grew as a result of it being at the crossroads of these two great railroads. The I & G.N. would become one of the oldest and most important parts of the eventual Missouri Pacific system, spanning a total of 1,106 miles.

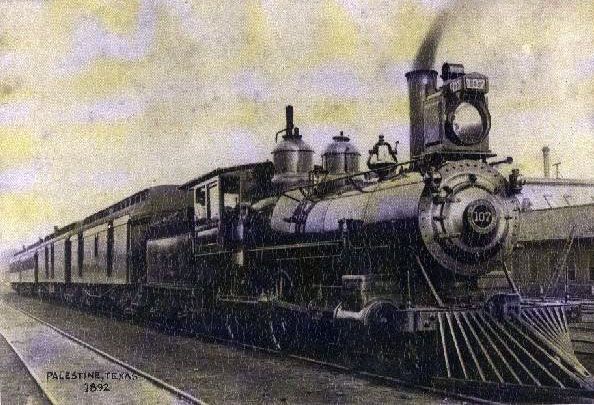

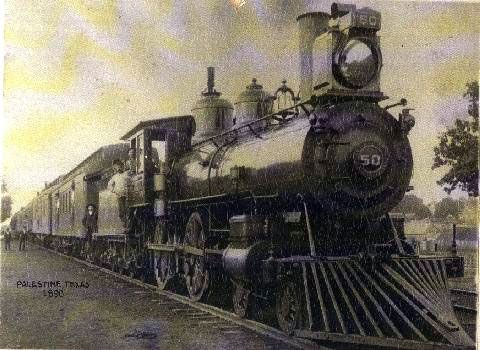

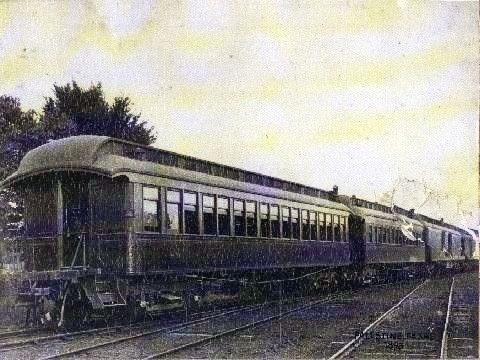

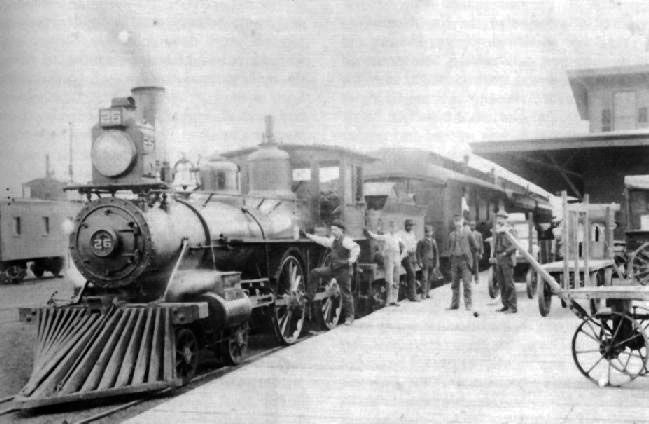

1890's International and Great Northern rolling stock

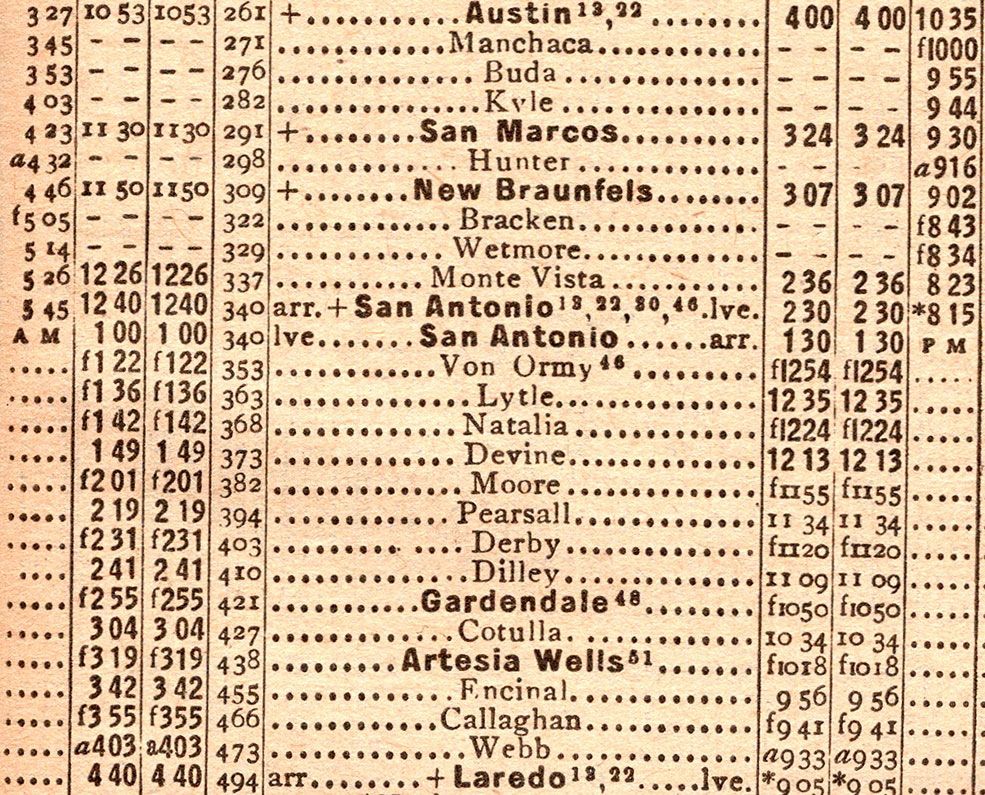

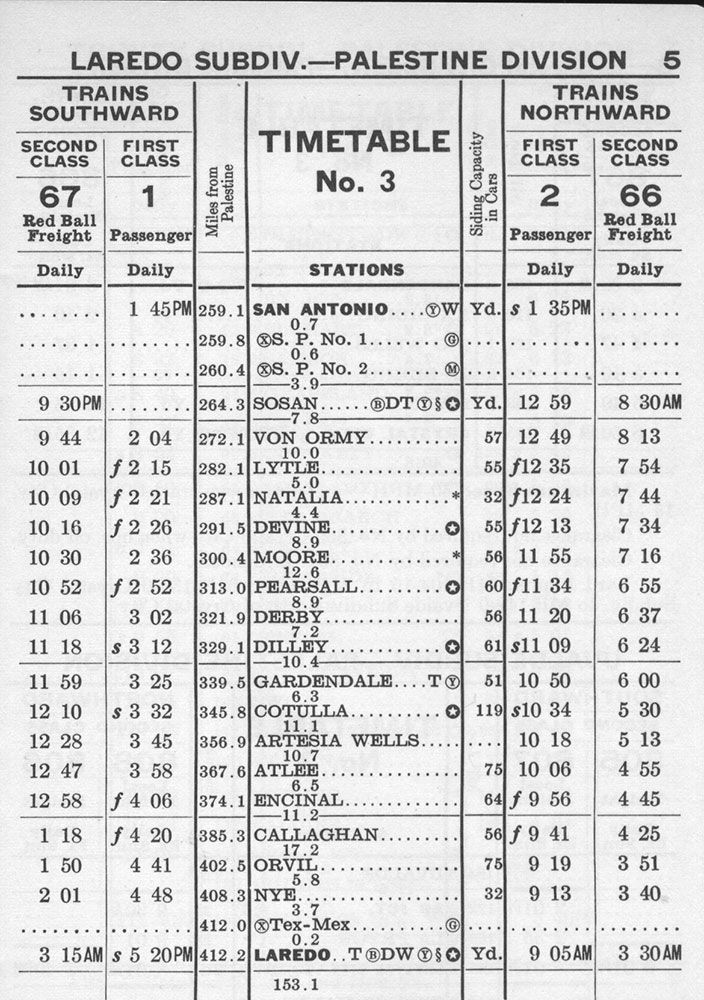

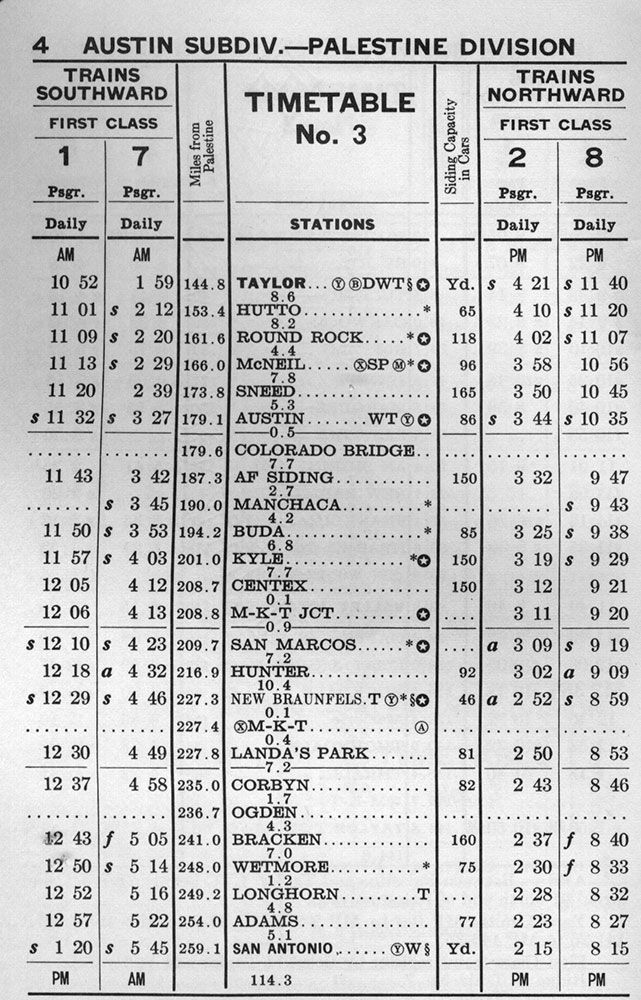

The International & Great Northern Railroad began service to San Antonio on 1/1/1881. The company line began as the International Railway Company in 1870. It was planned to build to Arkansas near a point on the red river and make connections to a railroad under construction from St. Louis. Construction began in Hearne and Palestine was reached in 1872. Longview, which would become the company's most northern point, was reached the following year. In 1873, the company joined forces with the slightly older Houston and Great Northern. The H & GN had built to Palestine from Houston. The new company began its southward trek and reached Austin in 1876. The I & G.N. went into receivership on 4/1/1878 and came out on 11/1/1879. It went into receivership again in 1881 and permission from the creditors had to be sought in order for the additional 153.7 miles from San Antonio to Laredo could be completed, which they were on 12/31/1881. Also in 1881, Jay Gould gained control of the I & G.N. when it was leased to the Missouri Kansas Texas, which was itself leased to the Missouri Pacific. For all intents and purposes the three were run as if they were one company, despite a lack of legal formalities.

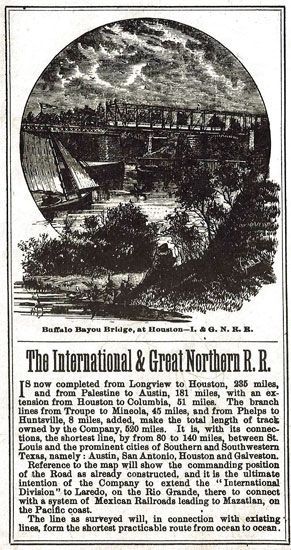

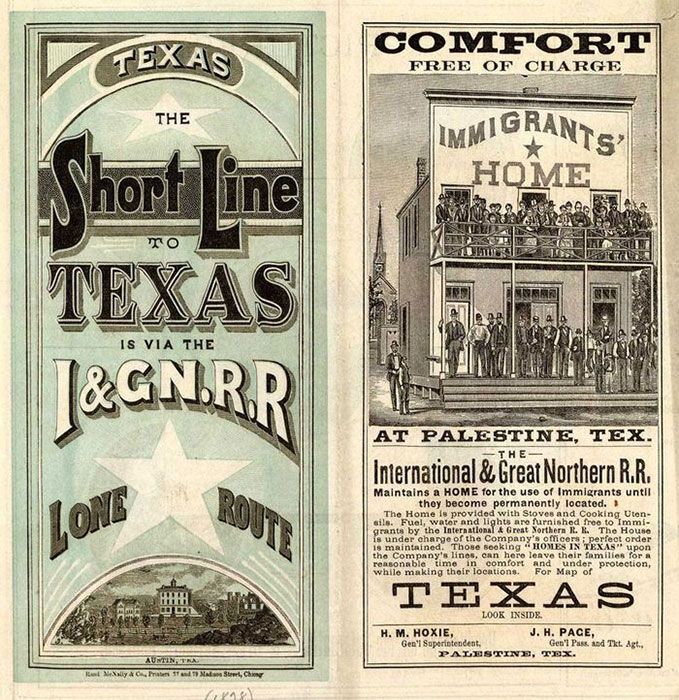

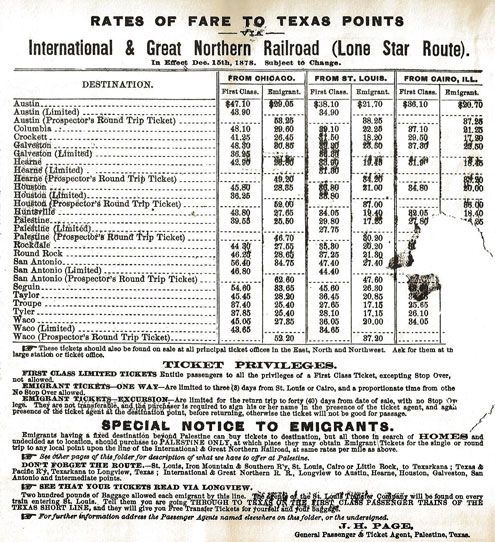

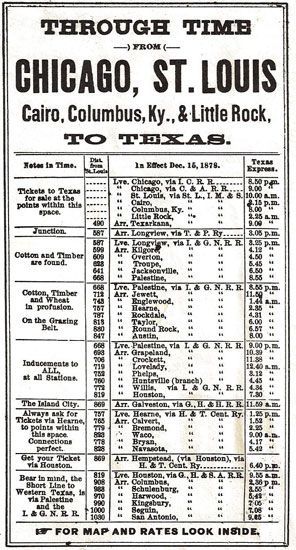

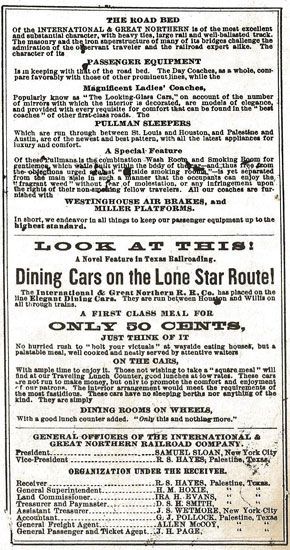

1878 images from an International and Great Northern Immigration brochure

Once the I &GN had reached Houston in 1878, the company promptly began advertising service to San Antonio, via the Galveston, Harrisburg and San Antonio tracks between Houston and San Antonio. (It would take another two years for the I & GN to build from Austin through San Marcos and New Braunfels to San Antonio directly.) They issued a lengthy brochure from which just a few pages are included above. It's interesting to note that the railroad offered different rates for would be immigrants, who were allowed to bring 200 lbs of belongings with them as part of their ticket. Low cost meals were also available on the train, which took around 50 hours - just over two days - of constant travel to get from Chicago to San Antonio. This compares most favorably with the weeks it would have taken by either land or sea before the advent of rail service, with the capacity to bring far less in the way of possessions. The price for this "speed and comfort was high, however. For first class passengers it cost $56.40, which is the equivalent of $1,258.92 in today's money. Maybe because of the additional personal freight, immigrant's had to pay $84.75 for their tickets, the equivalent of $1,891.73 today.

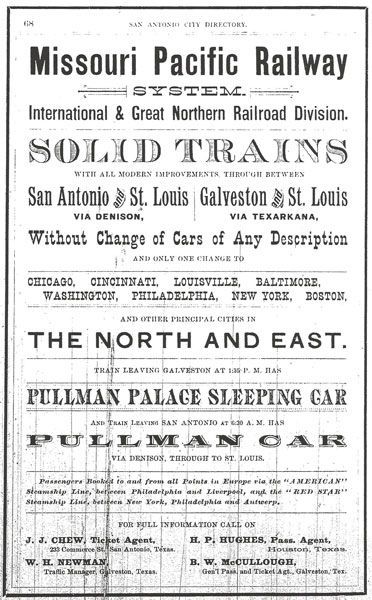

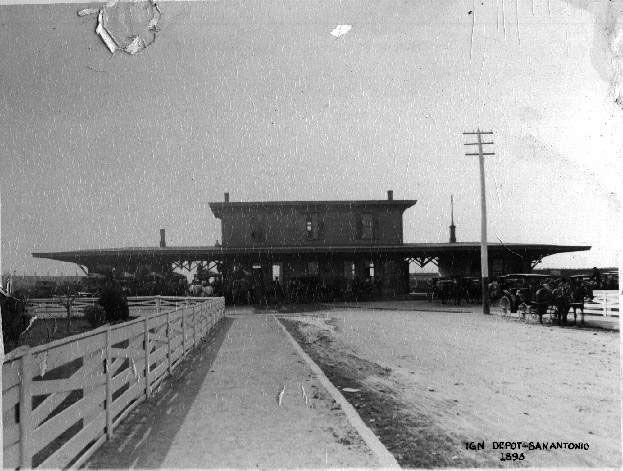

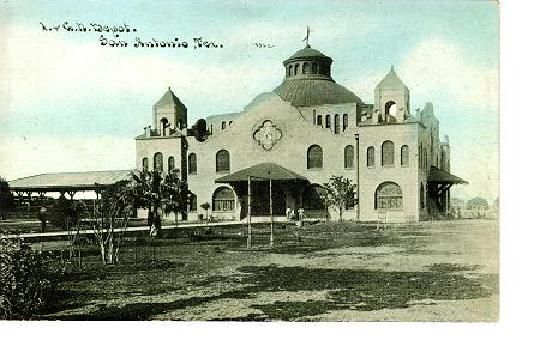

I &GN advert in the 1885 San Antonio city directory and two

rare images of the FIRST I & GN depot in San Antonio, 1893.

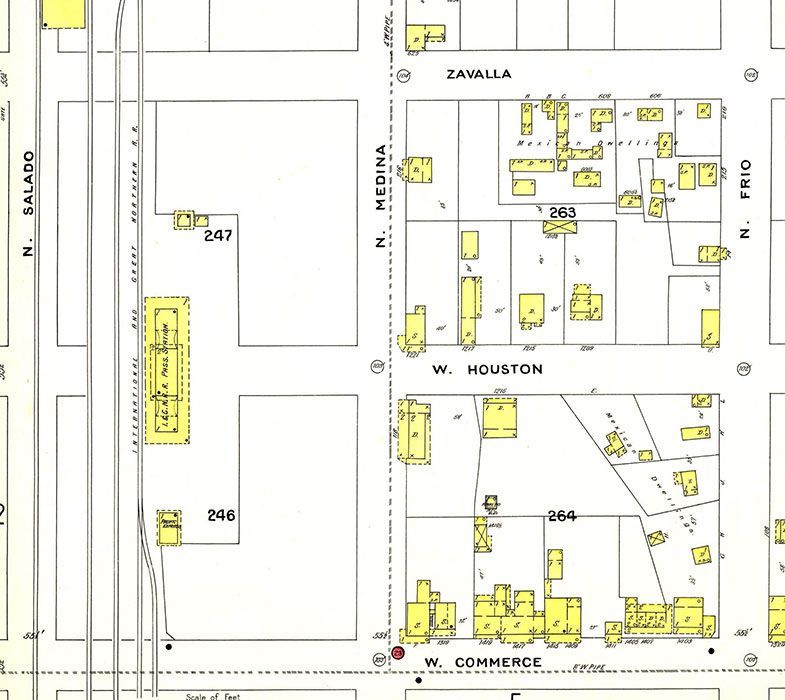

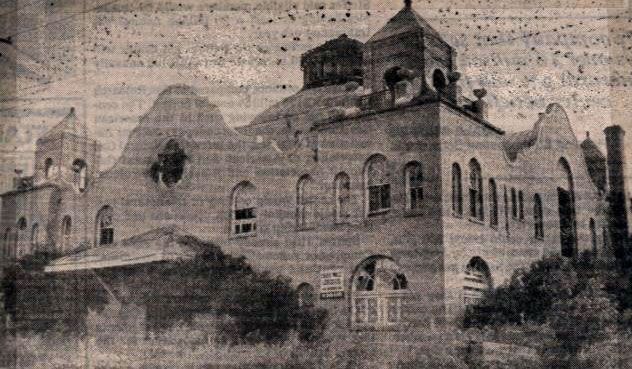

The first I & GN depot in San Antonio was nowhere near as impressive as the one that would replace it and which still survives today. Nevertheless, it indicated a serious commitment on behalf of the railroad to providing service to the rapidly growing city which, with the help of the railroads, would become the largest in Texas from 1900 to 1930. The depot was a frame building with a lunch room, waiting room, ticket office and an express baggage room. The city extended mule drawn street car service to the depot almost immediately. The first electric traffic light erected in San Antonio was put in on Commerce Street opposite from this older depot in 1900, so business was obviously good.

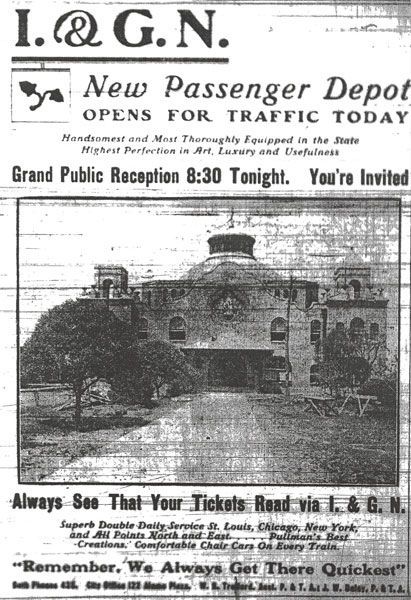

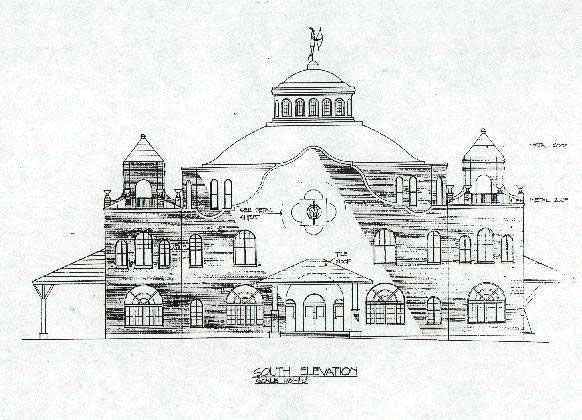

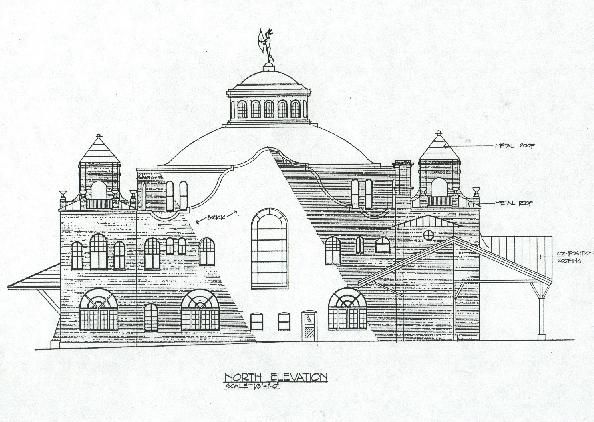

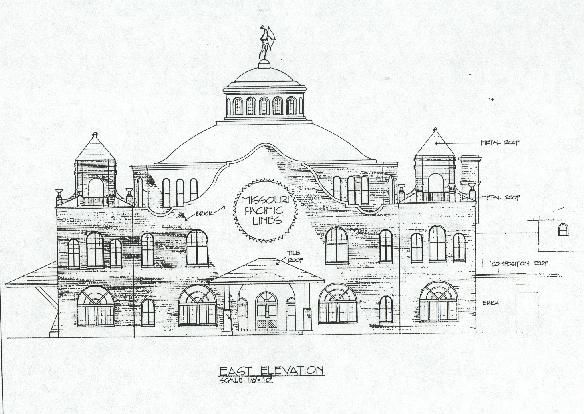

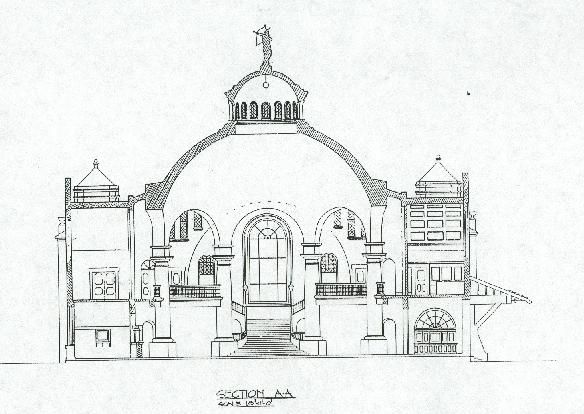

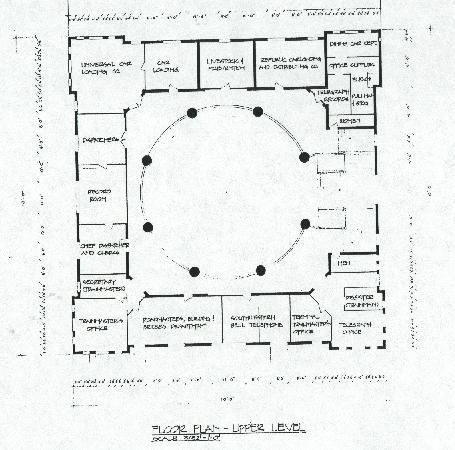

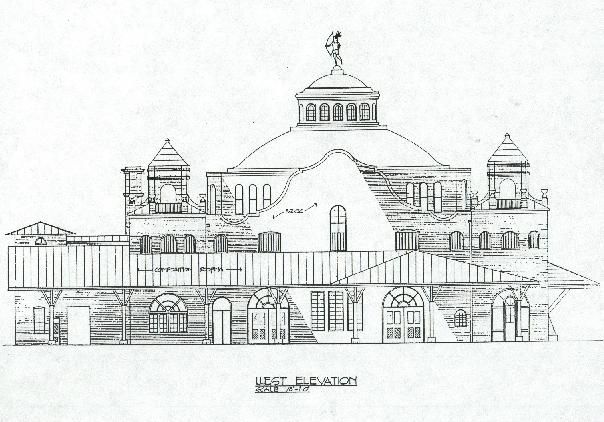

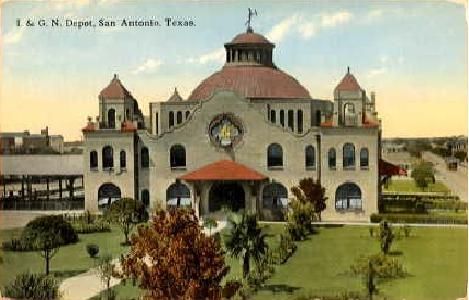

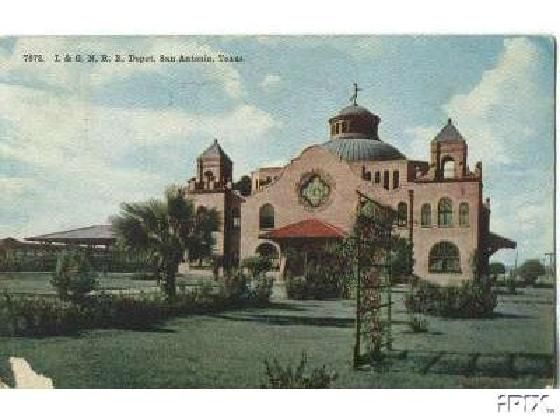

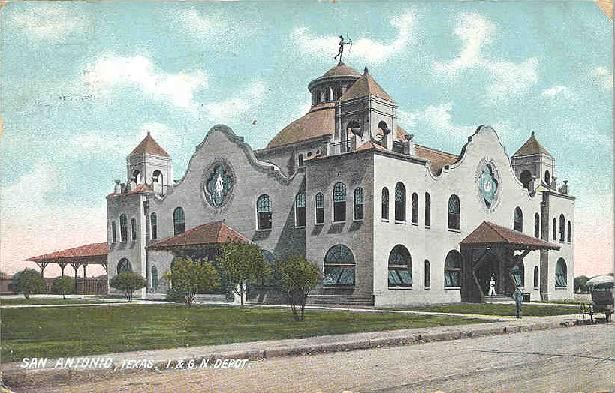

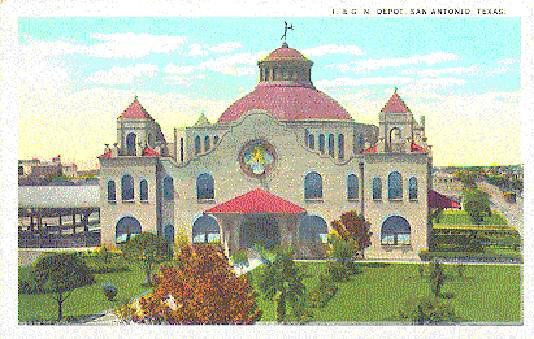

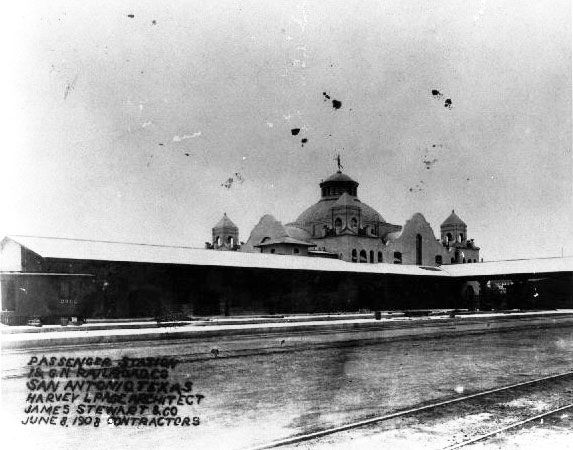

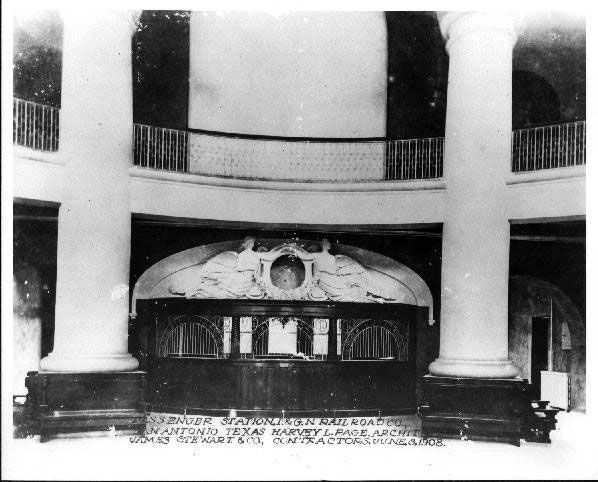

Station architect, Harvey L. Page, 1908 opening announcement, and

modern renovation architectural drawings, showing the original layout.

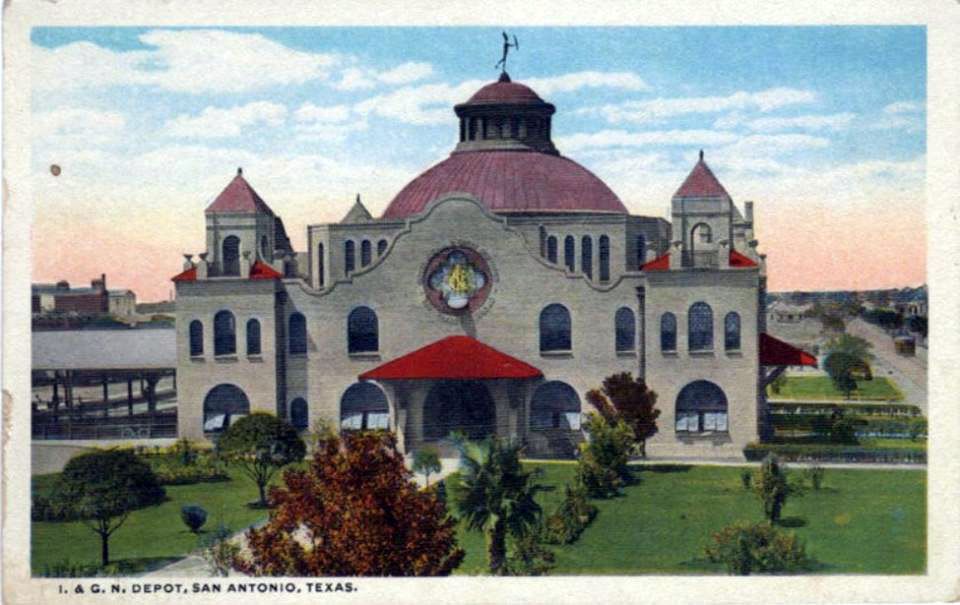

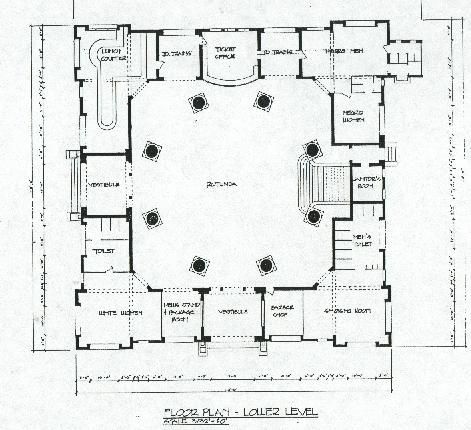

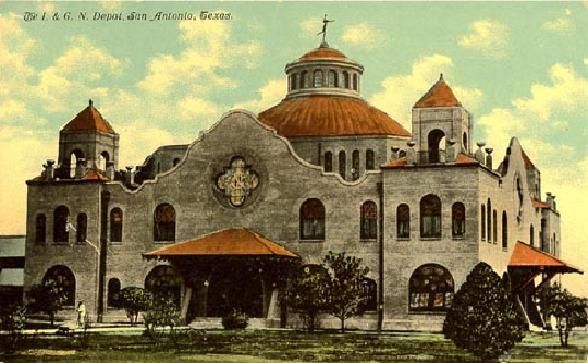

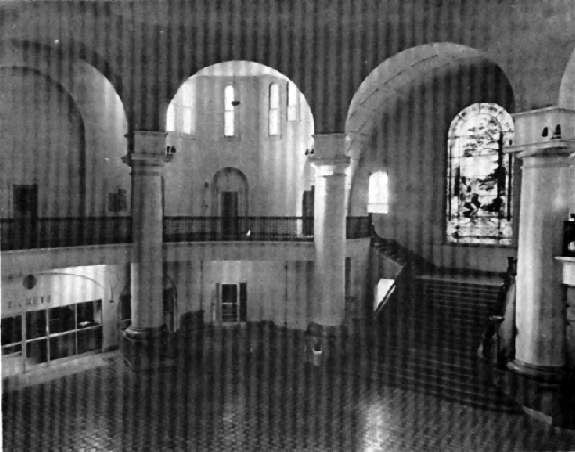

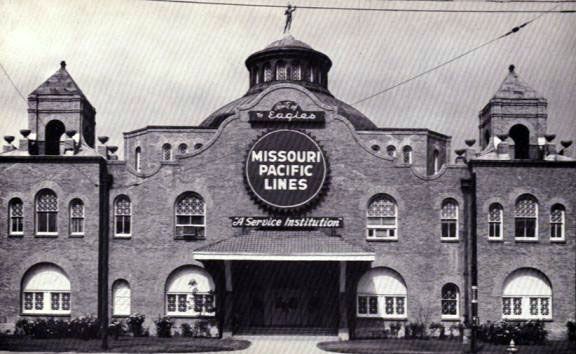

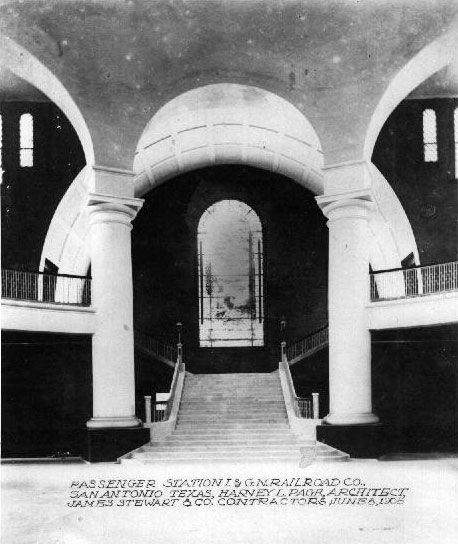

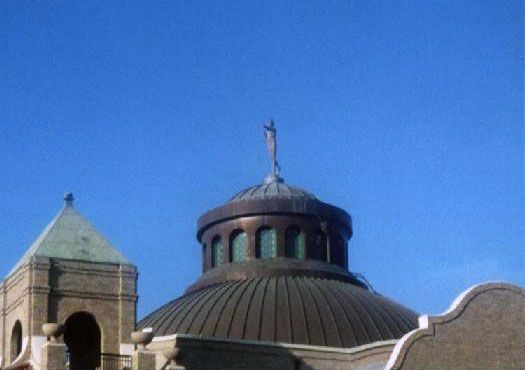

The "replacement" depot was begun in 1906, opened in 1907 and completed in 1908. It was significantly grander in every respect and, as a cathedral of commerce, it reflected the optimism of the era and the central role of the railroad within the economy. It was designed by Harvey L. Page (1859-1934), and built by the James Stewart & Co. Building company, whose main office was conveniently located immediately opposite the depot on Medina Street. Mr. Page moved to San Antonio in 1900 with his second wife, in part to escape the scandal which was a divorce back in those days. The depot is one of the remaining Page buildings. Two other significant ones are Temple Bethel and the Masonic Temple, in San Antonio. The depot is square, 110 X 110 feet, and the dome is 88 feet high. The Indian, of course, adds a few more. Mr. Page was justifiably proud of the depot and described it as his "Taj Mahal".

The magnificent depot was completed in 1908. It is a most impressive structure, which was exactly the intent of it's architect and the railroad It is made of compressed brick and stone and cost, even back then, some $142,000.00. Hardly chump change. The amazing thing is how often the railroad was foreclosed on and put into receivership, and yet the trains ran, buildings like this one were constructed, locomotives and rolling stock were bought, then replaced by larger, stronger, faster types. Great railroad empires are made from and comprised of, a national system, regional feeder systems and any number of smaller district lines that connect to them. In 1881 the rather famous, indeed notorious, Jay Gould gained control of the I & G.N. while it was in receivership. Mr. Gould's management of the I.& G.N., The Missouri Kansas Texas and the Texas Pacific led to the rise of James Hogg to the governorship of Texas in 1890 on a platform of bringing the railroads under control. The I & G.N. was singled out as being particularly unsafe. As a result, Gould's monopoly was broken and the various companies regained independence. Gould died in 1892. His family and supporters did retain control of the I & GN. This hold was not broken until around 1917. The company remained closely allied with the Missouri Pacific, but the relationship was one of ownership and was not legally set out in any other way.

The I & G.N. was foreclosed upon on 7/28/22 and re-chartered on 8/17/22, under almost the same name. Regardless of the foreclosure, many improvements had been made and profits were rising at this time. The Frisco & Rock Island contracted with the receivers to buy the line but the Missouri Pacific successfully fought the purchase at the Interstate Commerce Commission on the basis that I & G.N has been used preferentially for Missouri Pacific traffic to Laredo for forty years. Acting for Missouri Pacific, the railroad was bought on 6/20/24 by the New Orleans, Texas & Mexican Railway Company, which was then bought outright by Missouri Pacific in 1925. 'MOPAC' then went into receivership itself in 1933, for 23 years! It was re-organized as the Missouri Pacific in 1956. It is worth noting that the final Missouri Pacific system in Texas comprised of thirteen lines. None were chartered or originally controlled by MOPAC. It participated in the construction of only two lines. And five, including

The Gulf Coast Lines were at one time controlled by another system.

Two smaller local railroads were absorbed by the Missouri Pacific; the

San Antonio Uvalde & Gulf Railroad in 1925 and the

San Antonio Southern, formerly known as the

Artesian Belt

in 1927. Both already used IGN lines and its station within San Antonio. The SAU & G line to Corpus Christi became the main line serving that city and San Antonio. (When the Southern Pacific acquired the San Antonio & Aransas Pass, also in 1925, it downgraded the SAAP line to secondary status and leased use of the "Sausage," as the SAU & G was affectionately known. The San Antonio Southern was purchased in 1927. It ran due south from the south west tip of Bexar County to a town called Christine, crossing the SAU & G at Jourdanton. Neither became part of the IGN, however. They were officially part of the MP's "Gulf Coast Lines," which, along with the Texas & Pacific, was another "division" of the Missouri Pacific operations in Texas.

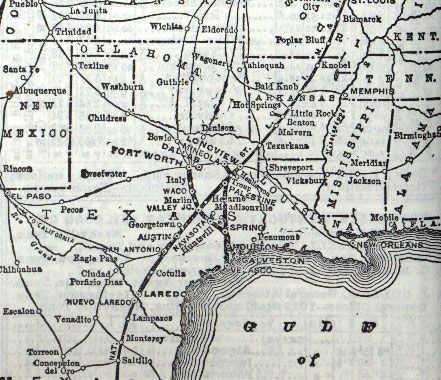

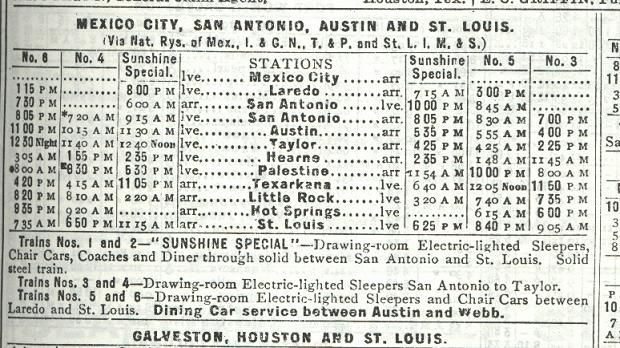

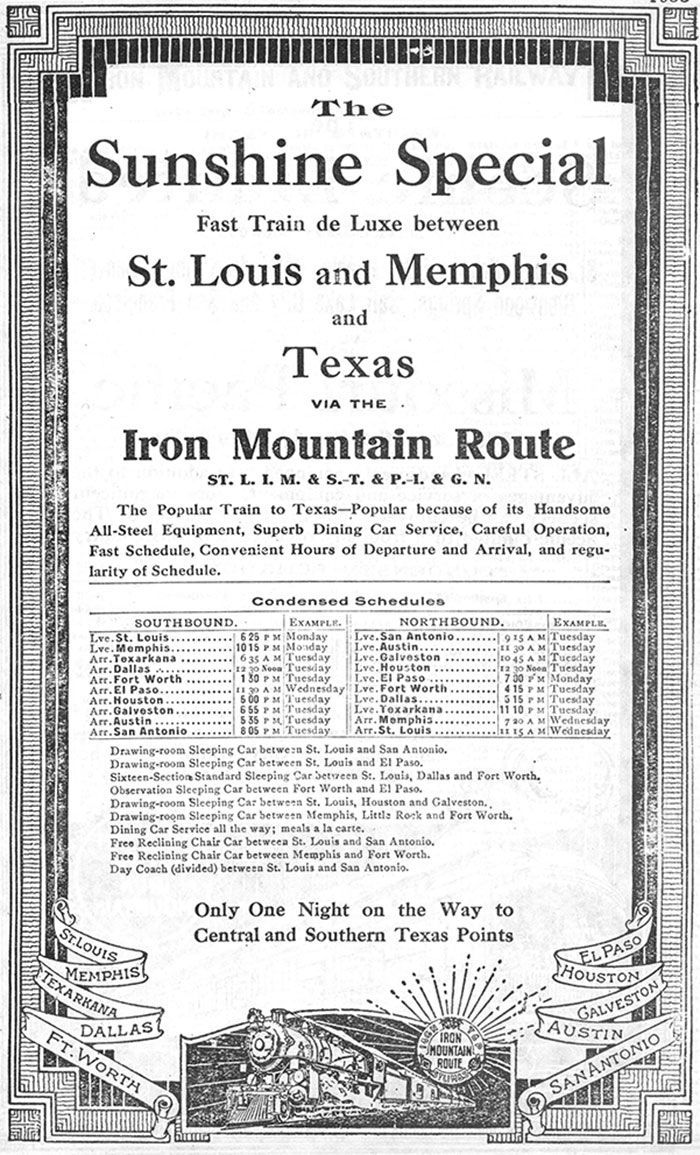

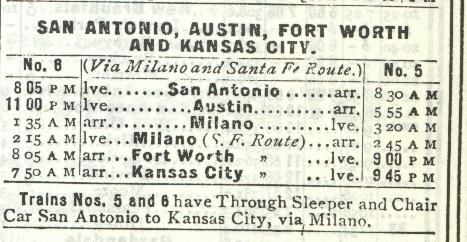

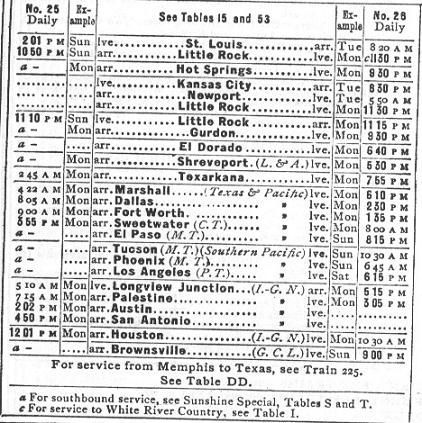

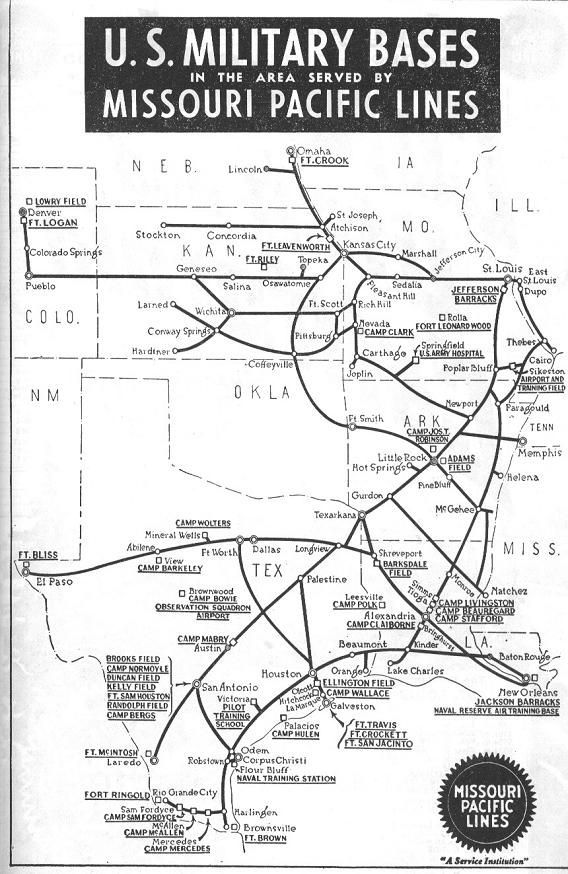

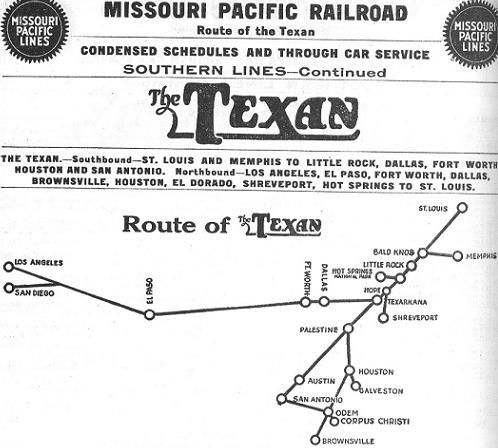

The IGN stretched from Laredo through San Antonio to Longview. There, via other parts of the Missouri Pacific passengers could continue through Texarkana, on into Arkansas and eventually reached St. Louis, Missouri. You could get to Dallas by switching at Longview. You could get to Fort Worth by switching at Valley Junction, outside of Hearne. However, the MKT ran directly to Fort Worth and Dallas and was, therefore, the more popular carrier to those cities. In 1930, there were three MOPAC "name" trains in both directions daily in San Antonio. "The Sunshine Special" arrived in San Antonio at 8:30 PM, twenty-six hours after leaving St. Louis. There was a connection in Texarkana for passengers traveling from Memphis, Tennessee. The train reached Laredo at 6:30 PM the following day. "The Texan" arrived in San Antonio at 4:50 PM, and also took 26 hours from St. Louis. "The Southerner" began in Chicago. It left at 6:50 PM daily. It ran through St. Louis, and arrived at its terminus in San Antonio at 8:45 AM, 40 hours, 15 minutes later. If you set off on a Sunday, you arrived on a Tuesday. There were a few other trains as well, including one to Houston but, again, this was by an indirect route and another carrier, the Southern Pacific, offered faster and more frequent service. There were two trains a day in each direction to Corpus Christi, the 211 / 212 and the 215 / 216. 215 left San Antonio at 10:15 PM and reached Corpus Christi at 4:30 AM. 215 left at 10:40 AM and arrived at the coast at 3:45 PM. Both took more or less six hours to travel the 150 miles. (Both trains had a parlor buffet.) There was one train a day each way from North Pleasanton to Carrizo Springs, departing at 7:00 AM, not very convenient for either of the trains leaving San Antonio. In addition, there was one mixed train every day except Sunday to Christine. Train 257 left at 8:00 AM and arrived in Christine, 54.6 miles away, at 11:15 AM, three hours and fifteen minutes. The departed on the return leg at 11:30 AM and was back at the IGN depot at 3:45 PM.

Like other railroads, the Missouri Pacific could not directly operate a railroad within Texas until the 1950s. It had to have a subsidiary company that was headquartered and operated in Texas. Created during the Gould years, the Missouri Pacific system within Texas was largely operated independently by the International & Great Northern, Gulf Coast Lines and the Texas & Pacific. The T & P was formed with the original intent of reaching California. The Southern Pacific beat them to it using the surveyed land the Missouri Pacific had a claim to. The final result became The T & P stretched almost to El Paso and then had trackage rights on the S.P.'s line. The I & G.N. remained an independent unit of the Missouri Pacific system until 1956 when it was folded into the parent company following its emergence from receivership, which had been entered into in 1933.

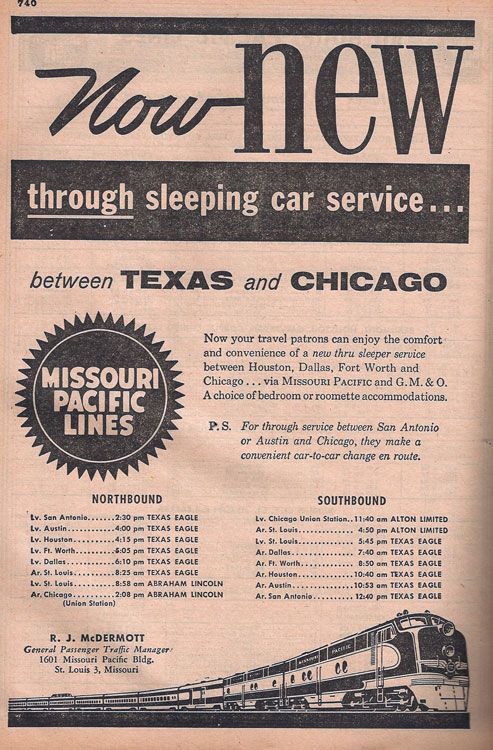

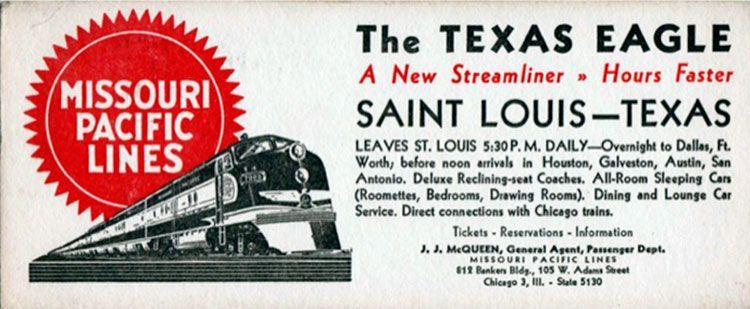

Passenger travel by train began to decline long before WW II. As roads improved, and cars became more affordable and reliable, people relished the independence that automobiles gave them. Modern airliners after the war were simply the nail in the coffin. Railroads evolved into being exclusively freight carriers, and long distance passenger service, despite the introduction of new streamliners like the "Texas Eagle," which replaced the "Sunshine Special," really became a thing of the past. One by one, railroads abandoned passenger service, except for higher density commuter services in the north east of the country. Soon, once independent companies began to consolidate into huge conglomerates. Long gone are competing lines to the same destinations, and huge freight trains whistle past boarded up depots, those that have not been demolished, that is. The Missouri Pacific was eventually bought by the Union Pacific on December 22, 1982. Only shadows of a once glorious past exist, because in our haste, so much was allowed to be destroyed.

But, for over sixty years, travel by rail was the only common sense way to go. Rails united the country. The first Texas legislatures after the civil war did everything they could to connect Texas to the rest of the country. Politics and greed impeded progress, of course, and certainly that has not changed much, except now its the airlines begging for money to keep going. Governor Hogg made sure no line could be chartered in Texas that was not controlled in Texas and created the Railroad commission to ensure Texans were served equally and fairly. Well, up to a point. Racial discrimination persisted, as you can see from the floor plans of the original depot. San Antonio can be proud of the fact it was the first city in the south to desegregate public services. Eleanor Roosevelt, who after WW II would perform almost heroic feats of diplomacy with regards to the Declaration of Human Rights by the United Nations - try arguing about that with a representative of Josef Stalin - is seen here arriving at the MOPAC depot in 1937.

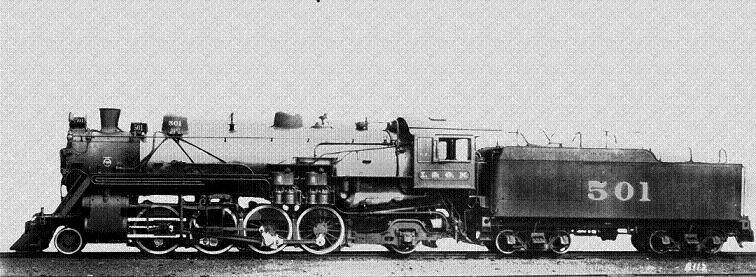

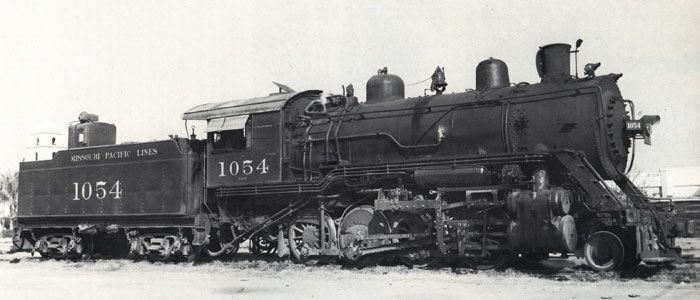

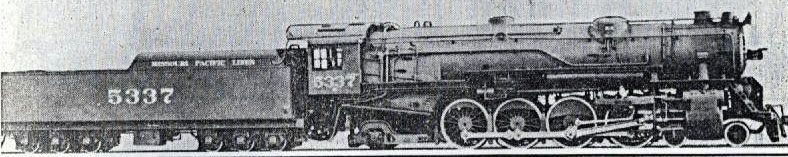

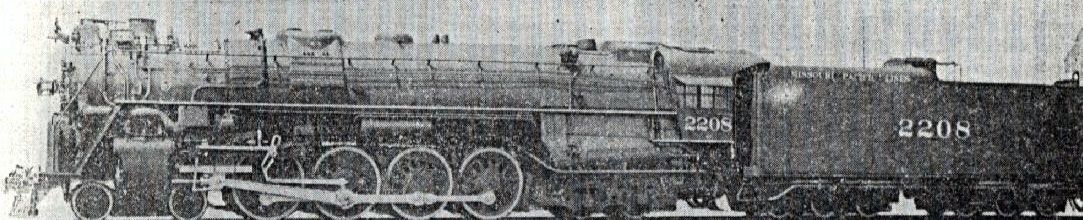

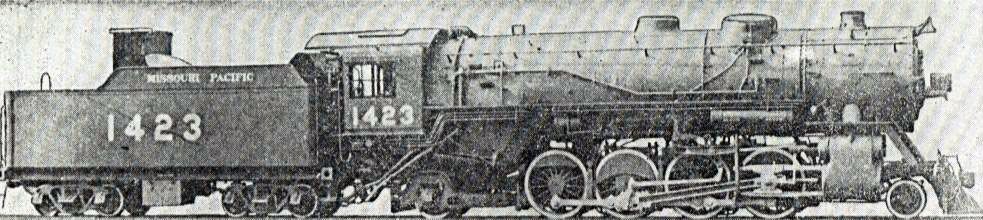

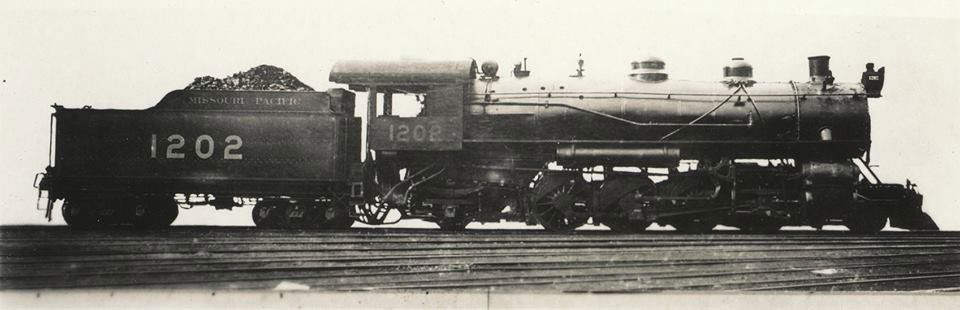

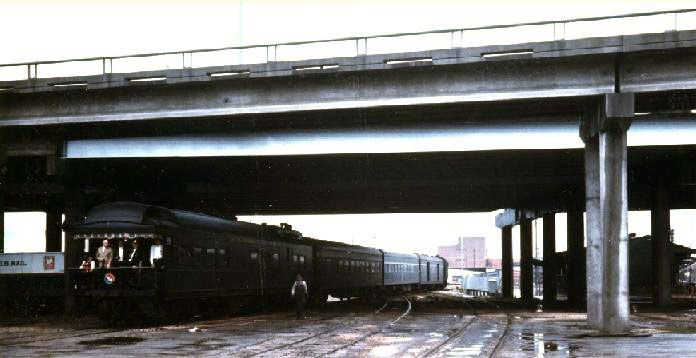

A variety of Missouri Pacific Steam Locomotives

The most profitable time for passenger service was during the year's of WW II. Prior to the war, the Missouri-Kansas-Texas line was the most popular, but after the war Missouri Pacific and Southern Pacific dominated trade. But business was diminishing and once proud trains, such as the "Eagle," which began in Laredo and ran all the way to St. Louis, became pale shadows of their former selves. By 1965, only one train a day left from San Antonio, a far cry from the dozens of departures and arrivals the depot once handled. 'Eagle' service was unceremoniously discontinued on 9/21/1970. The train had two passenger cars, and only carried ten people from Laredo. Not a single passengers boarded in San Antonio. And that was it. The local papers reported the end of the line for the Eagle a day or so later, with a sense of awe, that something everyone had taken for granted for so long was no more. Train enthusiasts were shocked that there had been no announcement ahead of time, which, at the very least, would have afforded them one last ride. They could not have saved it. According to Missouri-Pacific, the train was losing $50,000 a year.

When AMTRAK took over passenger service, the Eagle did continue to stop at the depot, for a while. But, because the building was boarded up, you had to get your ticket at the old Southern Pacific depot, thirteen blocks to the east on Commerce Street. The "Texas Eagle" name was re-introduced by AMTRAK after an attempt to run a service into Mexico, called the "Inter-American" failed.

An interesting T.T.M. postscript to Missouri Pacific passenger service is that the museum's owned observation car, the "Clover Glade," former MKT #1511, was regularly used for trips down to Laredo. This was a time when there were loads of surplus, unwanted, passenger cars literally hanging around. Most of these cars did not survive due to neglect and vandalism, and most were scrapped, although some were used by AMTRAK, which ran just about whatever was available in its early days. TTM's trips lasted from 1967 to 1970. The "Clover Glade," which was restored by the museum, still survives but not at TTM. It is now at a railroad museum in Temple.

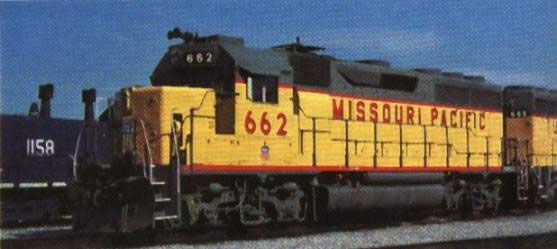

On January 8, 1980, to a stunned reception, it was announced that the 11,469 mile Missouri Pacific would merge with the 9,420 mile Union Pacific. The "take-over" had been kept secret up to the last possible moment. It would also include Western Pacific, which the Union Pacific already owned, more or less. According to the 4,300 page document presented to the Interstate Commerce Commission, the resulting system would have 22,800 miles of track, 54,000 employees and be run by a new company, Pacific Rail Systems, Inc. Ten other railroads, particularly the Southern Pacific, and also the Santa Fe, lodged furious legal campaigns to thwart the merger, which, along with many hearings, took two years to resolve. With the granting of trackage rights to a few competitors, the merger was approved on 9/13/1982 and, final legal appeals to the Supreme Court having been denied, was put into effect at 2:55 PM on December 22, 1982.

In May of 1984, the Missouri Pacific announced it was adopting the Union Pacific's yellow and gray color scheme and that it's locomotives and other rolling stock was to be renumbered to avoid conflict with Union Pacific equipment. As the merger progressed, Missouri Pacific identity began to fade completely. The last MOPAC locomotive acquisitions were made in 1987. By 1992, the name was gone. However, it is commonly believed that it was Missouri Pacific management who were really in charge of the new conglomerate. In subsequent take overs and "mergers" acquired companies would be integrated into the UP empire much faster. The MKT is totally invisible now. It is hard to find anything but a faint trace of its existence. You still see a lot of Missouri Pacific rolling stock in its original paint even after all this time. Like wise Southern Pacific locomotives and rolling stock, as that merger is less than ten years old. It is worth noting that many railroad historians consider that it was the take over of the Missouri Pacific by the Union Pacific that led to the eventual down fall of the Southern Pacific. The massive new company would prove to be impossible either to emulate or compete with alone. The Southern Pacific also end up being "merged" with the UP in 1996.

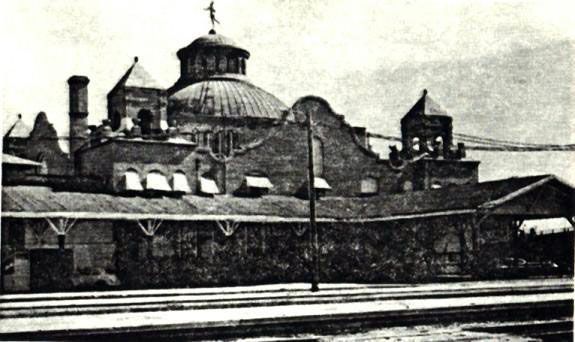

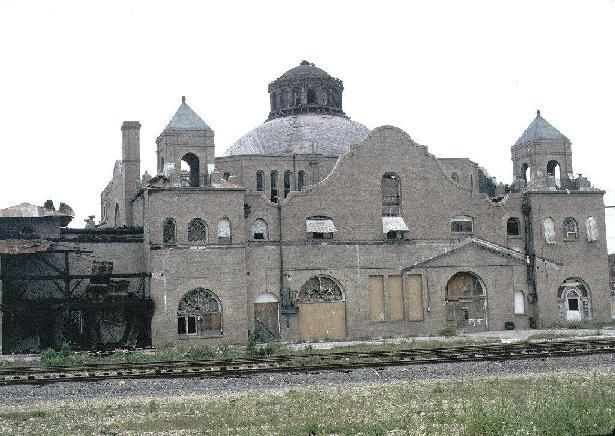

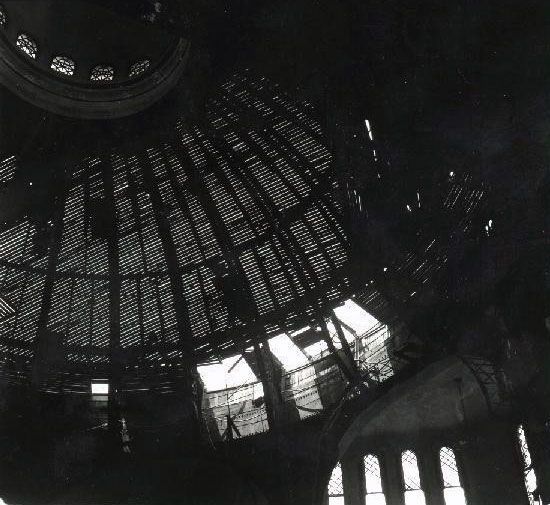

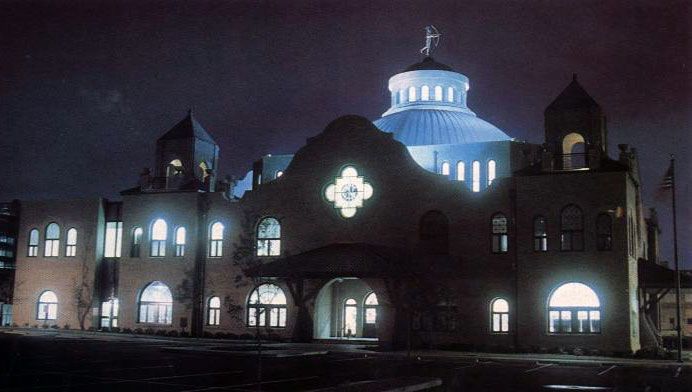

The magnificent depot was vacated by the Missouri Pacific around 1970 and lay desolate and abandoned for over fifteen years. This author has been able to see (and is now able to present here) some pictures of the building just before the San Antonio City Employees Federal Credit Union, now called Generations FCU, began a full restoration. The dome was in tatters, and most of the windows were smashed, including the large I & GN stained glass windows. Plaster had fallen from the walls, and interior column plinths were decayed and cracked. Detritus of every imaginable kind was strewn everywhere. Though the building was listed on the Register of Historic Places in 1975, that in itself failed to halt the decline in the building's structural integrity. We really should appreciate the phenomenal bravery of the credit union. No one else dared to attempt to rescue this building, which was right on the edge of being too far gone to save.

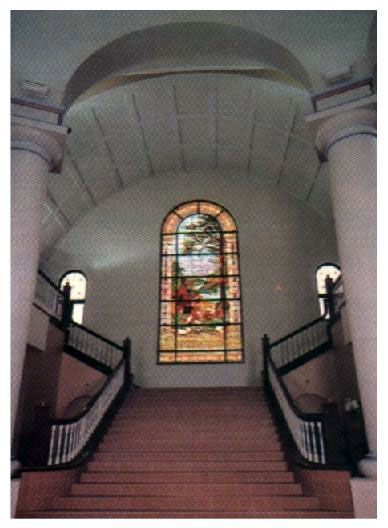

A stair case with a history. From 1907, to the 1980s and the present

Missouri Pacific sold the building in 1972 to a private owner, who himself sold it three years later, having failed to find a use for it. A Jerusalem native, Efraim Abramoff, president of Orah Walls Construction bought it in 1975. Mr. Abramoff, only resident in San Antonio for six years at the time, bought the building out of a desire to see it maintained for the future, and also because it reminded him of buildings in his old home town. During the buildings abandoned years, some twenty different proposals were put forward. The first owner tried to make the place into a heritage center, with an upscale restaurant upstairs. Another very serious proposal was from the Veteran's Administration, who considered using the place as an outpatient and benefit center. All those plans fell through, while time, theft and vandalism continued to take its toll on the structure.

Of particular interest to intrepid thieves was the brass on the dome. And, of course, once this was gone, the roof was no longer water tight and decay was accelerated even further. A fire on 6/4/82, probably started accidentally by vagrants, hardly helped matters.

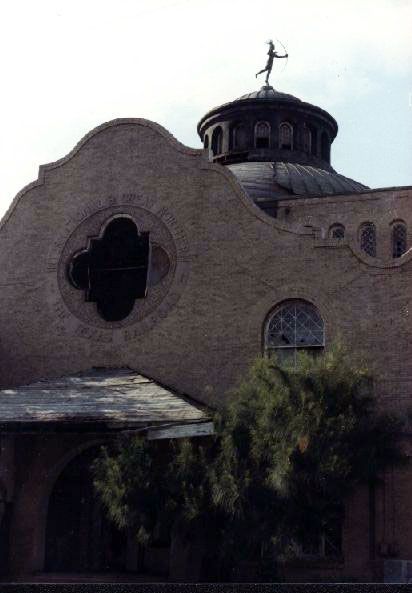

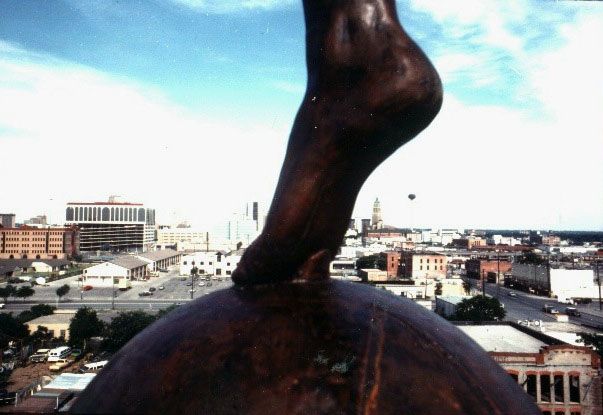

Restoring the Indian to its rightful place atop the San Antonio station dome

Also in 1982, the year that Missouri Pacific was bought by Union Pacific, the Indian which had stood atop the dome for so many years, mysteriously vanished. A concerned local business owner had been warning the authorities for some time that the statue did not seem to be stable and might come crashing down. When it did indeed go missing, she rallied quite a hue and cry, which drew in not only the police but the city council and even the FBI. The statue, which by this time was being speculated to weigh two tons and be of solid brass, was discovered in an abandoned lot only blocks from the depot. Badly damaged, even shot twice, the poor old relic was retrieved and put into long term storage. It was a banner day for the building and a feather in the headband of City Employees credit union on the day the statue, fully refurbished at considerable expense by the credit union, was restored to its lofty vantage point.

San Antonio City Employees Federal Credit Union spent a phenomenal amount to restore the building. They have maintained both its exterior and interior integrity and have created for themselves and their members a fantastic main office while helping to ensure the future of this outstanding building for future generations. Their efforts, made with the guidance of several civic organizations, particularly the very effective San Antonio Conservation Society, a group which has done so much to save the soul of San Antonio, attracted a lot of attention and won the credit union a good many awards. A wonderful building has been saved and put back into public service. Trains still use the adjacent tracks. With only a modicum of imagination, you could be back in the old days. San Antonians should count themselves lucky.

As you have seen in previous pictures, the three main stained glass windows were destroyed. Once the credit union decided to take over the building, they had to decide what to put in these gaping holes. Of course, it would have been entirely legitimate to put in something that indicated their own institution. Even the Missouri Pacific railroad covered one of them up with their own logo. But, in keeping with the credit union's decision to maintain the integrity of the original structure, they decided to restore the originals as closely as possible. Blacks Art Glass was commissioned. They recreated the windows from old photographs and used shards of the original glass, scattered around the interior for color matching. The price? A mere $50,000!

The full story of the credit union's decision to acquire and restore this building could easily be the subject of a good sized book. They were only ten days away from signing on some land several blocks away from the depot on which the were going to build a brand new building. They were asked to give the old depot a look over by city officials. This author cannot imagine the process by which it was decided to give up the new building and take this instead. In case you think they were offered financial incentives, grants or tax abatements, be aware neither were they offered nor were they requested. For a variety of reasons almost beyond the imagination, they opted to bring the building back to public use. Furthermore, although they were at liberty to do what ever they pleased with what was essentially a wrecked structure, they decided to take the high road and do it right. The restoration cost $3.1 million. This was less than they would have paid for their new building. The project came in under budget and ahead of schedule. James Resnick was the project architect.

Of the original structure's 19,000 square feet, only 7,000 was usable office space. The credit union decided to add an extension to the track side of the building. Though the new wing is not an exact copy of the old building in every detail, most people, including, I admit, this author, would be fooled into thinking it was. It is located where once the old track shades and sheds once stood. From the front, the windows match and even on the track side, the various openings match those on the old exterior wall, which is still there, only now as an inner wall. Justifiably, the restoration has received much praise and many, many awards. The National Trust for Historic Preservation named them in their list of fifteen best projects in 1988. It was the only project in Texas to make the list and the first time ever for San Antonio since the awards were begun in 1946. The Texas Historical Commission followed suit, as did the San Antonio Conservation Society.

Images from April 2020

In the mid 2010's VIA Metroplitan, the Bexar County commuter bus company, acquired the building and has transformed the nearby area in its major downtown intermodal bus hub.

Missouri Pacific in San Antonio Timeline

━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━

1851

The Missouri Pacific (MOPAC) RR is formed

━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━

1866

The Houston & Great Northern RR (H & GN) is formed

━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━

1870

The International Railway Company (IRC) is formed

━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━

1873

The International & Great Northern (I & GN) is formed by the merger of the IRC and the H &GN

━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━

1881

January. The I & GN builds into San Antonio, goes into receivership yet manages to reach Laredo by December under the control of Jay Gould's MOPAC, which leases the I & GN to another of his subsidiary companies, the Missouri, Kansas & Texas (MK & T)

━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━

1891

In a a wave of anti-railroad sentiment where Gould is singed out as the worst kind of operator, he loses control of the MK & T but manages to keep the I & GN

━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━

1900

San Antonio's first traffic control device, a stop sign, is erected near the original I & GN passenger depot

━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━

1907

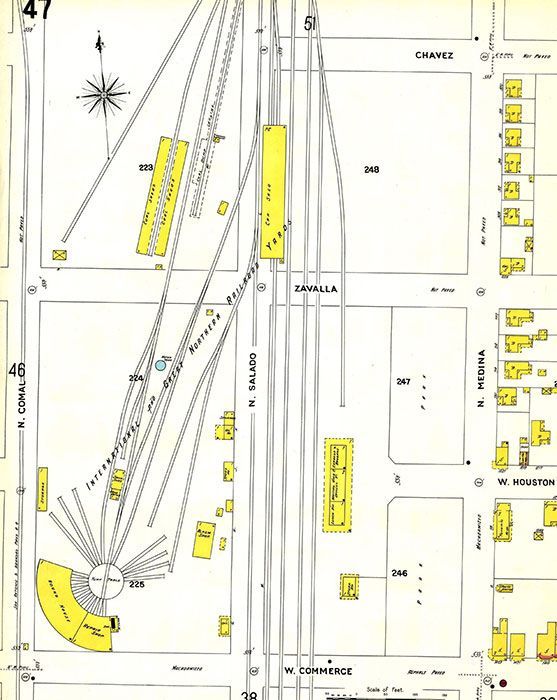

A new, grand, passenger station is opened by the I & GN at the corner of Commerce and Medina. A freight depot operates on the other side of Commerce Street. A small yard complete with round house and turntable is nearby. The I & GN also operates a much bigger freight facility called the East Yard accessed from Quintana Road on the south east of the city.

━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━

1915

MOPAC begins operating the "Sunshine Special" from Laredo through Arkansas and points north. Other passenger trains include "The Texan" and "The Southerner."

━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━

1922

The I & GN is purchased at a foreclosure sale by the St. Louis - San Francisco, (SLSF), often referred to as the Frisco. MOPAC challenges the purchase in court, and wins.

━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━

1924

The I & GN is formally by MOPAC's New Orleans, Texas & Mexican (NOTM) division

━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━

1925

The NOTM division is formally acquired by MOPAC and folded into its Gulf Coast Lines (GCL) division

MOPAC acquires the San Antonio, Uvalde & Gulf (SAU & G) and folds into its Gulf Coast Lines (GCL) division

━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━

1926

MOPAC acquires the Asherton & Gulf and folds into its Gulf Coast Lines (GCL) division

━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━

1927

MOPAC acquires the San Antonio Southern (S A S) and folds into its Gulf Coast Lines (GCL) division

━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━

1933

MOPAC goes into receivership from which it will not emerge for 23 years.

━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━

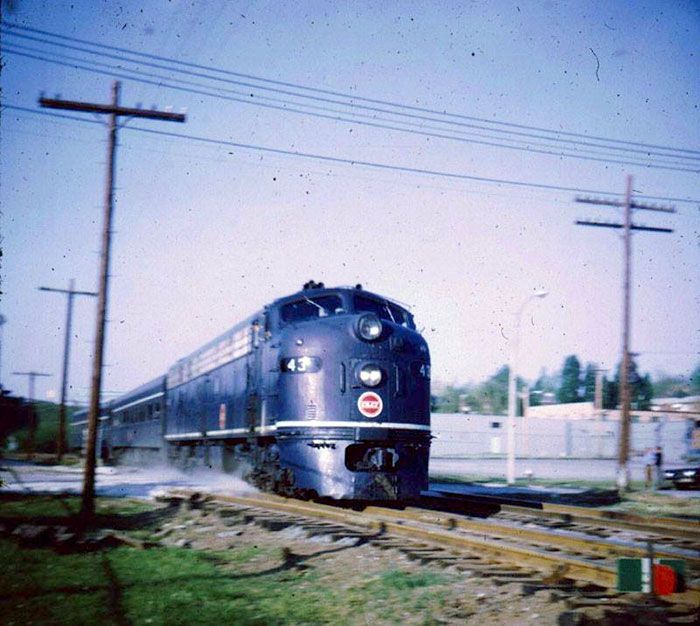

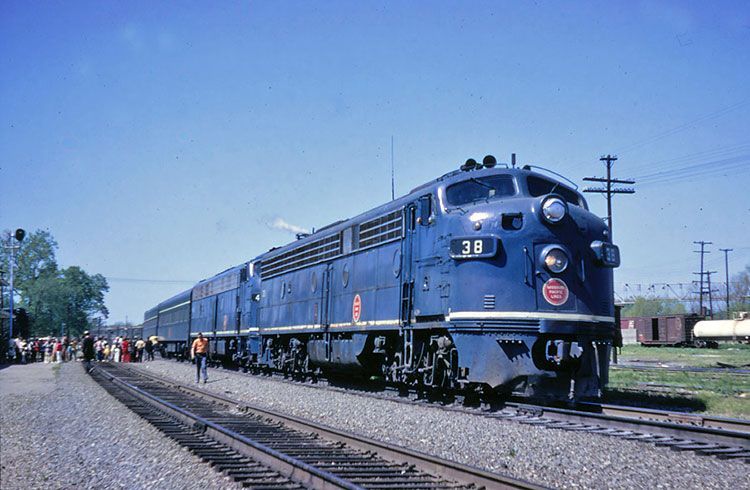

1948

MOPAC introduces the diesel-electric powered, stream-lined "Texas Eagle" between Laredo and St. Louis. Complete with air-conditioning, the train is very popular in the immediate post WW2 era.

━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━

1952

The "Sunshine Special" is pulled by a steam locomotive for the last time, signifying the end of MOPAC steam power

━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━

1956

MOPAC exits receivership

━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━

1958

MOPAC abandons the old A & G line to Asherton

━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━

1959

MOPAC abandons the old SAU & G line between Pleasanton and Gardendale

━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━

1963

MOPAC abandons the old S.A.S. line to Jordanton

━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━

1965

Passenger service from the MOPAC railroad station in San Antonio is down to just one train a day, the "Texas Eagle."

━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━

1970

MOPAC ends "Texas Eagle" service and shutters its passenger station. The old freight station is lost when a bridge to carry Commerce Street traffic over the railroad tracks is built. The nearby yard is closed. The Bexar County Jail occupies some of the land once used by the yard.

━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━

1975

The once magnificent MOPAC station in San Antonio, now in serious disrepair which will continue for another ten years, is placed on the national register of historic places

━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━

1980

MOPAC announces its merger with the Union Pacific. MOPAC is actually the larger of the two in terms of track miles but, when the deal is finally given federal approval two years later, it is the Missouri Pacific which loses its identity

━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━

1981

AMTRAK reintroduces the "Texas Eagle" between San Antonio and Chicago

━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━

1985

The San Antonio City Employees Federal Credit Union (now called Generations FCU) restores the old depot and begins using it as its main office

━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━

1988

The SACEFCU wins San Antonio's first ever National Trust for Historic Preservation award for its sensitive restoration of the former Missouri Pacific railroad station.

━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━

1990

The UP abandons the old SAU & G line between Gardendale and Crystal City. A short lived independent company tried to keep it going but fails within two years.

━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━

2011

Generations FCU sells the old MOPAC station to VIA Metropolitan Transport, the local bus company, which intends to make it an inter modal terminal that integrate its soon to be built street car service with buses

Transportation Museum

CONTACT US TODAY

Phone:

210-490-3554 (Only on Weekends)

Email:

info@txtm.org

Physical Address

11731 Wetmore Rd.

San Antonio TX 78247

Please Contact Us for Our Mailing Address

All Rights Reserved | Texas Transportation Museum