Rails Between San Antonio and Corpus Christi

Several museum members followed the railroad route of the San Antonio and Aransas Pass railroad from San Antonio to Corpus Christi and back along the San Antonio, Uvalde & Gulf in late 2004 and early 2005. The San Antonio and Aransas Pass tracks are mostly removed except for some 40 miles. Sixteen of these miles are between downtown San Antonio and Elmendorf. Thirty-two are at the other end, between Sinton and Aransas Pass. We visited some of the S.A.& A.P.’s key junctions on the way to Corpus Christi. On the return home we travel alongside the very active line built by the San Antonio, Uvalde and Gulf Railway, nicknamed the "Sausage". From its first through trains in 1914, the official name has morphed through Gulf Coast Lines, Missouri Pacific, and finally, Union Pacific.

To Corpus Christi via the San Antonio and Aransas Pass

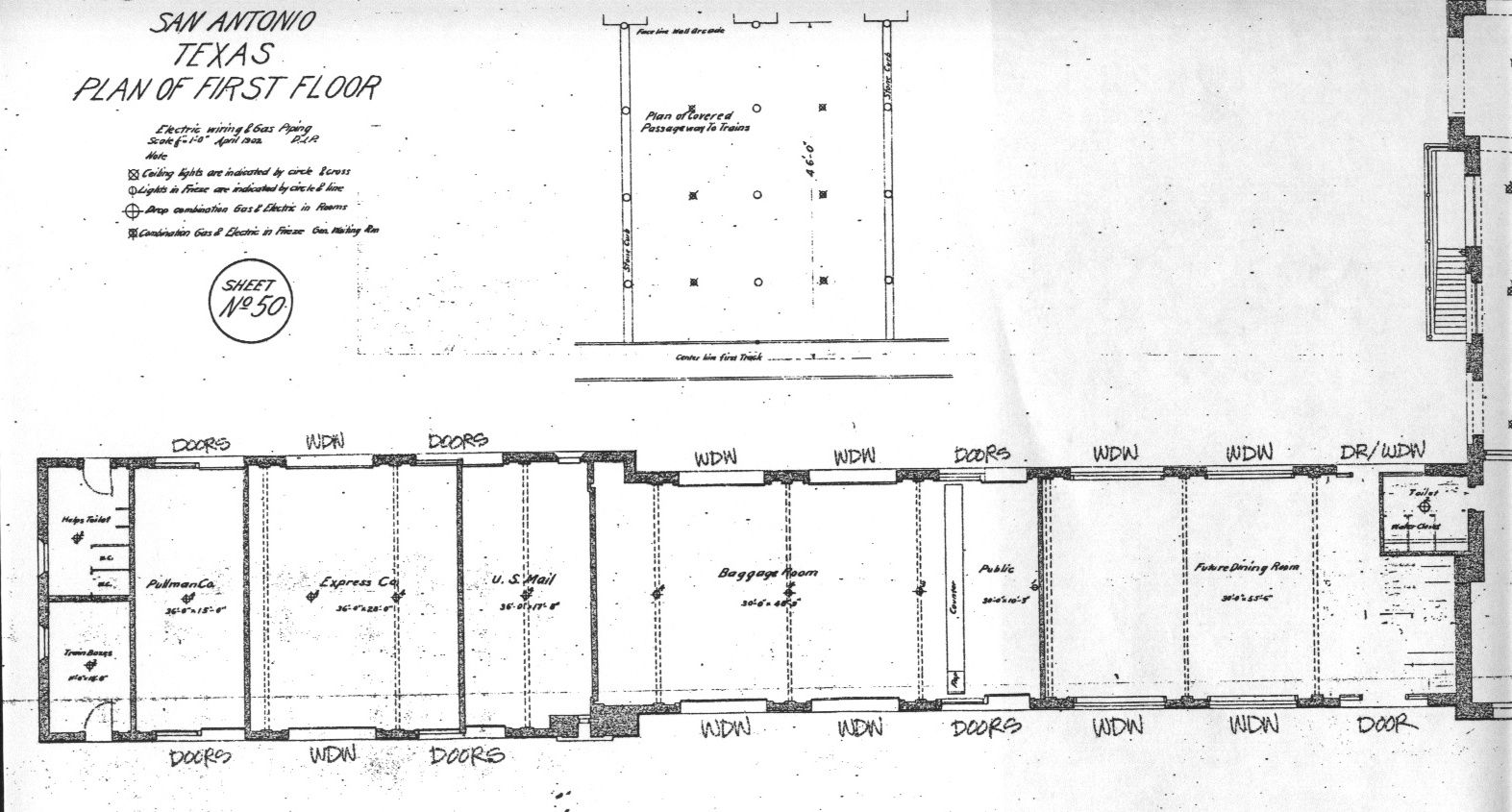

Our trip’s original mile zero was on the south side of the San Antonio business district, near the intersection of present-day Flores and Alamo Streets. In 1886, the San Antonio and Aransas Pass opened its own two-story wooden passenger station. It remained for the next 39 years. At its peak (1910), the San Antonio and Aransas Pass launched four passenger trains daily from San Antonio. One operated to Kerrville, taking just 2 hours and 45 minutes and averaging 26 miles per hour, including the nine scheduled intermediate stops. A second train was the morning train to Houston and Corpus Christi. The train split in Kenedy. A third train was the afternoon passenger train for Corpus Christi. It, too, had some car shuffling to do at Kenedy. Cars for Houston were uncoupled, and coaches from Waco to Corpus Christi were attached. These two-day trains took 6 12 hours to amble down to Corpus Christi from San Antonio at a blistering pace of 23 miles per hour, even slower than the Kerrville branch. The last train of the day was the road’s pride and joy, “The Davy Crockett” which carried standard sleeping cars for Houston and was advertised as the “”train that is always on time”. No wonder since it maintained an average speed of 24 miles per hour. By splitting off cars at Kenedy, the "Davy Crockett" also became the night train to Corpus Christi, carrying a string of three tourist sleeping cars south of Kenedy: one from Houston, one from San Antonio, and a third from San Antonio to Rockport. The next morning’s stop at Gregory, (8:05 a.m.) was important not only to separate the Rockport car, but also to provide breakfast for the passengers. The S.A.P. never operated a dining car. Such was the S.A.P passenger service at its prime. In 1903 it ceased using most of its own south side depot in favor of the Sunset Station, keeping only its upstairs offices at the original location. During World War One, downstairs became an army officer's club.

Little did the road’s builder, Uriah Lott, know in 1886 that the first 16 miles out of San Antonio, both north and south, would one day be the golden miles that are still in operation. Sixteen miles to the north, on the old Kerrville Branch, is the Fiesta quarry. Immense unit trains of 100 cars or more pull sand and aggregates from this quarry once and sometimes twice each day. Sixteen miles to the south is Elmendorf, site of three huge coal-fired furnaces, with potentially a fourth to come if CPS gets its way. At one time, Elmendorf boasted a very acceptable depot, but this is long gone. Relatively clean-burning coal from Wyoming’s Powder River Basin occupies the unit trains that keep the fires hot and the steam pushing the generators to produce power for a hungry San Antonio. Finally, little did the builders know that the then-infant chemical industry would establish four huge plants on the “chemical coast”, along 30 miles of still-active track between Sinton and Kosmos (near Aransas Pass).

The active line from San Antonio can be followed by traveling on Presa Street (route 122) down near the missions along the San Antonio River. (After all, this was billed as “The Mission Route”). You will eventually come out on Route 181. Follow route 181 another 14 miles past Elmendorf (City Public Service, the utility operating the Elmendorf furnaces, is not too keen about visitors entering on their access roads without prior permission). After some thirty miles you will be in the charming town of Floresville. The town square is several blocks from the station, which sits on concrete-filled tubes approximately where it once commanded the town’s commerce along 1st Street. It has been ten years (1994) since the last train served Floresville. Several grain elevators remain, now served by trucks.

By remaining on route 181, travel 7 more miles to S.A. & A.P. milepost 38, you can’t miss Poth station.. The tile roof and stucco-sided station has recently been refurbished and is in good shape. The rail for the siding is still in place, and it appears like they are grading the right of way as preparation to laying track on the other side. Oh that this were true! The small but interesting Poth historic district is just across the street.

19 miles further down the line is Karnes City, where we saw much evidence of where the tracks were, but found no station.

Six miles beyond Karnes City, at S.A. & A.P. milepost 63, is the once important junction of Kenedy. A few blocks of track still remain. The old station was situated in this area. Immediately after the station, the line divided; one branch followed the road to the far left, curving off towards Houston. The other line continued straight ahead to Corpus Christi. The charming and historic downtown of Kenedy is still quite vibrant with active shops. It has been ten years since a freight train whistled past those cross bucks and 52 years since the last passenger train (Numbers 313 and 314, the San Antonio section of the Border Limited) stopped here in 1952 with through cars for Corpus Christi and Brownsville.

Travel 32 miles on route 181 and arrive in the largest town on the S.A. & A.P. between San Antonio and Corpus Christi, Beeville. Amazingly, Beeville kept its freight trains until 1996 when the track from here to Sinton was removed. Still, looking south, the track through the center of town is intact, as are the switch stands and cross bucks. Even milepost 93 is still on the pole to the left, just beyond which was the Beeville passenger station. Nearby, the once-busy Victoria Branch from Houston entered this line.

Eleven miles south of here is Skidmore, where the Alice branch originally diverted (important for its connection at Alice with the Texas Mexican Railway and passage to Laredo). In 1927, the Southern Pacific extended the Alice branch into the Rio Grande Valley all the way to Brownsville. Officials of the Southern Pacific were overjoyed at the thought of giving the rival Gulf Coast Lines some competition down in the Valley as well as opening up the Laredo gateway for themselves. This was the year that the S.P.'s 'Border Limited' was launched with great fanfare.

Some rail is still buried in the weeds at Skidmore, once an important point on the 'S.A. & A.P..'. Straight ahead was the Corpus Christi Branch, and curving off through the brush here was the Alice Branch. Each night at the witching hour of about 2:30 a.m. four passenger trains would meet here. Trains # 313 and 314 were San Antonio-Corpus Christi trains, while # 303 and 304 were Houston-Brownsville trains. By shuffling and interchanging their cars here at Skidmore, passengers from both Houston and San Antonio had their own sections of the 'Border Limited' by which they would ride through to either Corpus Christi or Brownsville. While nearby Beeville might have seemed a more logical spot to do this shuffle, Skidmore had more open land and fewer crossings. Motorists and nearby residents might find the maneuvers somewhat noisy and annoying if they had been held in Beeville. After 1927, this eleven-mile stretch of the S.A.P. was the busiest section—so busy the dispatchers rigged up a rudimentary form of centralized traffic control. Hard to believe this pioneering form of traffic control and all of those trains are now gone!

Continuing down Route 181, we parallel the S.A. & A.P. another eighteen miles. The roadbed and ballast appear quite fresh here, as it was only eight years that this portion of the line was abandoned. In fact, at approximately milepost 123, two tracks suddenly appear and these two tracks are filled with freight cars. Current owner, Union Pacific, has left intact this two-mile spur off the old St. Louis, Brownsville and Mexico diamond in Sinton (and once the S.A.P mainline) for the sole purpose of storing several hundred “surge”cars. These are older but serviceable cars that may be required should the railroad experience an unexpected surge in business. If the railroad has to wait too long for the surge, the scrap dealer will get these cars.

At Sinton you look east on the old San Antonio and Aransas Pass line. The truncated track was once the main line leading to the diamond that crossed of the old Missouri Pacific line. The S.A. & A.P. arrived in Sinton in 1886, some 21 years before the north - south line (St. Louis, Brownsville and Mexico) arrived to form the crossing. Sinton was named after a stockholder of a manufacturing plant that located here shortly after the arrival of the S.A. & A.P. When the St. Louis, Brownsville and Mexico arrived here in 1907, the officers and directors of that road invited the S.A.P to join them in erecting a Union Station at the crossing. But the competitive relationship between the Gulf Coast Lines (Missouri Pacific) and the Texas and New Orleans (Southern Pacific) was simply too intense to allow much of any cooperation. The S.A. & A.P. kept their own station in Sinton, located barely one quarter of a mile from the then new SLBM depot at the diamond. (Both buildings are now gone.) The SLBM wanted to lease trackage rights from Sinton to Corpus Christi in 1907, thus allowing their passenger trains from Houston access to the port city. The S.A. & A.P. refused to give this permission, forcing the SLBM to travel another 21 miles south on their line to Robstown, site of their crossing with the Texas-Mexican Railroad. (see map). The Tex-Mex officers and directors were amenable to trackage rights for the SLBM. This situation prevailed until 1914, when the San Antonio Uvalde & Gulf (AKA "The Sausage") came along with their own crossing at Odem. The Odem gateway into Corpus was short and direct. The SLBM made a trackage rights deal with the Sausage and Odem has been the principal gateway into Corpus Christi ever since. The historic business district of Sinton is a jewel! The track from the crossing still connects with the old SLBM. There is also a leg from the old SLBM mainline to the biggest remaining section of S.A.P. in the southeast quadrant of the diamond. This last stub of the S.A.P. provides rail access for some 30-miles to a point just north of Aransas Pass. This is now known as the "Chemical Coast" line as it serves several manufacturing facilities in this coastal stretch.

Still on highway 181, we travel another 16 miles with the S.A. & A.P. line, the "Chemical Coast," hard on our right side. It is great to be finally driving along tracks as opposed to empty rail bed that is rapidly becoming harder to find. We enter Gregory, which was once the separating point for the Corpus Christi Line and the Rockport line. The old S.A. & A.P. station is still there on the wye between the two branches. One line traveled to Portland and thence over Corpus Christi Bay on trestles and finally over the famous “bascule bridge” and the deep-draft waterway to enter the city of Corpus Christi. Today, the tracks still operate to Portland, the site of a major sand quarrying operation. The old through route to Corpus Christi now ends here, just short of the causeway. While through trains from San Antonio took this route, a shuttle train would load passengers for Ingelside, Aransas Pass and Rockport. This stretch of line is still there, for freight only, of course. Back in the old days, food was advertised as being available at Gregory but the service must have been rudimentary rather than a sit-down Fred Harvey sort of place. No recipes, memorialized in a cookbook, are known to have originated in Gregory.

Between its arrival in Corpus in 1886 and 1922 when it was forced to cooperate with the highway department, the Southern Pacific had much trouble with its wooden trestle across the shallow bay. It was demolished in a storm in 1919 and had to be completely replaced. You could see the old trestles from the train as you rode the replacement. These same shallow waters were impeding the desires of Corpus Christi to become a major seaport. Before the deep channel was dug, deep draft vessels would have to anchor off shore somewhere near where there was a water break (Aransas Pass) between those long and narrow sand strips called Padre Island and San Jose Island. Here the shallow draft tenders would off load the cargo and carry it across the treacherous sand bars into a wharf in Corpus Christi. This transfer process was slow, tedious and costly. Better that those deep draft freighters had a deep channel to enable them to come right into Corpus Christi. This endeavor took over seventy years to accomplish. The Corps of Engineers finally accomplished the task in 1924. Now, of course there was a deep water channel to be crossed. The COE constructed a Bascule bridge that had a single railroad track and two lanes of highway. The bascule design involves swinging up the entire span of the bridge to a vertical position to allow ships to pass through. They opened the bridge about thirty minutes before a ship announced it needed to pass through. This would allow the vessel to safely stop if the bridge raising mechanism failed to work. 1924 was the first year that highway access from Portland and beyond was possible. Prior to this you could only get there directly by rail.

By the late 1950’s, two things were apparent about the SP's attitude to Corpus Christi. The Southern Pacific Railroad had lost interest in much of its South Texas operations, including the extension to the Valley and the line into Corpus Christi. (They had always run hot and cold about a line they principally acquired to quell competition into Houston.) At the same time, the Texas highway Department was anxious to enlarge the capacity of what was becoming route 181 from Portland into Corpus Christi. The highway bought the rail right of way across the bay, including the bascule bridge, from a Southern Pacific Railroad only too ready to sell it off. To avoid traffic delays, the new bridge was built at a height of 135 feet above sea level. The bascule bridge was removed. A stub of rail runs right under the city side of the "new" bridge but no train has burnished these rails in over 42 years. Directly in back of these rails, is the old S.P. yard, and perhaps a full mile along the line, stood the old station in downtown Corpus Christi. Sheds still remain in this yard area bearing the fading name “Southern Pacific” The highway elevations required by the new bridge wiped out the station itself. The highway clover leafs in downtown Corpus also did nothing for the integrity of the historic downtown district.

Having arrived in historic downtown Corpus Christi, hard by the old courthouse now under reconstruction, we conclude the first half of our trip which allowed a grand sojourn back in time along the route of the old San Antonio and Aransas Pass Railroad. Our return to San Antonio will be along the route of its one time competitor and now sole survivor. Before we continue, we shall pause to examine Corpus Christi and the railroads today.

Corpus Christi and the railroad

For much of the Twentieth Century, three railroads dominated rail traffic in Corpus Christi. There was the San Antonio and Aransas Pass, also known as the Texas and New Orleans or Southern Pacific, the San Antonio, Uvalde and Gulf, also known as Gulf Coast Lines or Missouri Pacific, and The Texas-Mexican Railroad. A drive around Corpus Christi today will show you that all three of these are now fallen flags. Today, there are three railroad companies operating in Corpus Christi, The Union Pacific, the Transportacion Ferroviaria Mexicana and the Corpus Christi Terminal Railroad.

The Southern Pacific abandoned the former S.A. & A.P. yard in 1960. This was due in large part to its reluctance to build a bridge that would be high enough to satisfy large ship navigation beneath it. Railroads are singularly poor at climbing any kind of grade and achieving 135 feet on both sides of the ship canal would have required many, many miles of gently rising tracks. As the old S.A.& A.P. yard was directly underneath the new road bridge, this is obviously impractical. Maintaining the bascule bridge was not an option. The channel to the port was widened at this time to allow access to larger ships and the bridge and its mechanism was removed. The S.P. could have attempted to build into the city by a different land route but the costs and the legal difficulties in acquiring right of way would have been enormous.

The S.A.U & G, acquired by Missouri Pacific in 1925, is now owned and operated by Union Pacific. Its old depot is the only one remaining of the three that once served the city. It maintains a small yard within the city and a larger one on the outskirts. It is the principal rail service to and from the city.

The Texas-Mexico Railroad is now owned and operated by TFM. In 1881, the Texas-Mexican Railroad began operating its 157-mile railroad from Corpus Christi to Laredo (this was five years before the S.A.P. arrived in town). While this railroad was started with capital from U.S. citizens and built by the same team of Uriah Lott and Mifflin Kennedy that built the S.A.P., it was struggling by 1900. A group of U.S. investors decided to incorporate the railroad in Mexico and infuse it with new capital. Why Mexico? Because Mexico at that time was very friendly to U.S. capitalists and encouraged investment with the promise of ample, low cost labor and favorable taxation. Mexico was in the 25th year of its 35-year Porfiriato (1876–1911), the 35-year rule of dictator Porfirio Diaz. The Mexican Revolution of 1911–1916 changed the picture for the Texas–Mexican Railroad. Populist rebels such as Pancho Villa, Emiliano Zapata and Pascual Orozco blamed the “foreigners” for plundering Mexico's wealth. For railroads, this meant all foreign-owned roads had to be “appropriated” and nationalized. The Texas Mexican Railroad retained its name but became solely owned by the Mexican government. It was to be the only railroad operating solely in the United States that was owned entirely by the Mexican government. Today, following privatization, TFM is 49% owned by the Kansas City Southern, though the Transportacion Ferroviaria Mexicana (TFM) retains the majority of its shares, 51%.

The third operator is the Corpus Christi Terminal Railroad. It is owned by the Port of Corpus Christi Authority and operated by a unit of Genesee and Wyoming Railroad. This terminal railroad was created in 1924 just as the deep-water channel to the Gulf was opening. To offer shippers the best service and rates, the Port Authority wanted the docks to be accessible to all three railroads of 1924. To assure this, they built their own railroad along the ship channel and made sure it was connected to all three of the competitors. Relations between the Southern Pacific and its competitors were strained, to say the least, though Missouri Pacific and the Tex-Mex found it mutually beneficial to cooperate. Corpus Christi wanted to maximize its new harbor's potential and not allow turf wars to jeopardize its success.

To San Antonio from Corpus Christi

via the San Antonio, Uvalde and Gulf

As we return to San Antonio, we follow the route of the "Sausage," which derived its nickname from its initials, S.A.U. & G., from south to north. Unlike the San Antonio and Aransas Pass, which has only a few miles remaining, the Sausage is an intact and working railroad, now owned and operated by Union Pacific, which also operates the remnants of the S.A. & A.P., along with the old St. Louis, Brownsville and Mexico (SLBM). Despite its dominant position, Union Pacific does not completely monopolize Corpus Christi. As mentioned, it has one actual competitor in this area. the Transportacion Ferroviaria Mexicana (“TFM”), the purchaser and operator of the old Texas-Mexican Railway, (Tex Mex). It also has a potential competitor: the Burlington Northern and Santa Fe, which was granted trackage rights into Corpus Christi from Houston on the old SLBM, when the UP took over Southern Pacific. Thus far, BNSF has limited its rights to moving between Houston and Laredo via TFM trackage. While the competition from BNSF is dormant, TFM has been very aggressive.

When the officers and directors of the S.A.U. & G. (the Sausage) decided to extend their railroad, originally called the Crystal City & Uvalde, to Corpus Christi, and change its destination and destiny, it was still to be decided if Corpus would be designated by congress as a deep port with the supporting federal funding necessary for the Corps of Engineers to undertake the task. What is known, however, is that the city of Corpus Christi was very unhappy with its existing rail service. Within four years of the arrival of the San Antonio & Aransas Pass, the city was demanding urgent talks with the company, and with Southern Pacific, its new owner. To improve their chances with their intense desire for deep water facilities, they offered a handsome bonus to the C.C. & U to encourage the struggling line to extend their line to the city. Other land owners along the way followed suit and the company turned south from Pleasanton and created a line that still exists today. For the first eight years (1914 to 1922) the "Sausage" was literally sweating it out. Congress passed the necessary legislation in 1922 and two years later, in 1924, the job was done. In 1925, the "Sausage" was purchased by Missouri Pacific and folded into its "Gulf Coast Lines" division.

The Tex-Mex, the S.A.P. and the Sausage each operated their own passenger depots in Corpus Christi. Of the three stations, only one is left—the Sausage. It is located downtown, near Belden and West Broadway. None were particularly grand. Initially, the San Antonio, Uvalde and Gulf station hosted a day train and an overnight train to San Antonio. From its inception, the 'Sausage' day train was an hour faster to San Antonio than that of the S.A.P. Of course the S.A. & A.P. train visited more towns of greater significance along its route. By 1916, traffic at the S.A.U. & G. station was augmented by two St. Louis, Brownsville and Mexico trains. Their flagship train was the overnight Brownsville to Houston train called "The Pioneer." Passengers wishing to travel to Houston from Corpus Christi would board "through cars" which included a sleeping car. These cars would trundle out the 17 miles to Odem late each night to meet the eastbound 'Pioneer.' This shuttle train would wait at Odem for the east bound Pioneer where cars for Houston would be attached and cars for Corpus Christi detached and shuttled into town. The SLBM also operated a day train between Houston and Brownsville (numbers 11 and 12). No Corpus-Odem shuttle was used. The Southbound train # 12 simply swung around the northeast leg of the wye at Odem. After making its station stop there, it took its entire train down the Sausage line, 17 miles, and entered the station in downtown Corpus. After completing its station work, it would reverse its operation for one-half mile to the 'Sausage’s' Port Avenue connector to the Texas-Mexican Railroad, two miles south. Moving through the northwest leg of the wye, the train would again be heading engine first. At Port Avenue Junction with the Tex-Mex, it simply took its entire train over 15 miles of Tex-Mex rails to Robstown, where a Southwest leg of the wye got it headed south on home rails once again. This entire operation added about an hour to the schedule versus a straight-through operation from Odem to Robstown, skipping Corpus Christi. For northbound train number 12, the procedure was reversed. This odd maneuver more or less put Corpus Christi out on the mainline and is, in fact, repeated every day today. Trains 11 and 12 are long gone, of course, but not so for the TFM freight trains. Three or four TFM freight trains retrace the very route of SLB&M’s Train 11 and 12, diverging at Odem, using the old 'Sausage' line to a connector line in Corpus Christi, thence over the connector to the old Tex-Mex and west to Robstown. Of course, at Robstown, these TFM freight trains simply rumble over the old diamond with the SLBM rather than use a southeast leg of the wye to gain their tracks. In fact, the southeast leg of this Wye has been removed.

In motoring out of Corpus toward Odem, it is apparent that the 'Sausage' occupies some lucrative industrial trackage, loaded with refineries, grain mills, gins, and direct access to the Port of Corpus Christi, whose deep water channel it parallels. The Union Pacific maintains a small yard in downtown Corpus Christi, just north of the old passenger station, plus a larger classification yard about 9 miles out at Viola. The Sausage’s next 8 miles to Odem are over swampy inlets and cannot be followed by automobile. It should be noted that these were expensive miles to build, not too different from the S.A.P.’ s watery entrance into Corpus from the north. Only the old Tex-Mex found a reasonably dry entrance into Corpus from Robstown.

Of the three railroad access towns for Corpus, that is, Sinton, Odem and Robstown, Odem is different. Sinton was established in 1886 and Robstown in 1907. The downtown districts of these two towns are tight and compact, reflecting the horse and buggy days and the need to be pedestrian friendly. Odem, on the other hand, came along with the Sausage in 1914 when the Model T was making the automobile a means for everyone to get about and not just a “rich man’s toy”. Odem was established as a highway town with wide streets and plenty of room for the “horseless carriage” to park.

The diamond at Odem is where the 'Sausage' crossed the older SLBM. Remarkably, three of the four diamond quadrants are still intact and active. The Sausage and the SLBM shared a “Union” station, even before the two roads were unified under the common ownership of Missouri Pacific's "Gulf Coast Lines." The station no longer stands, with the last 'Sausage' train stopping here in 1961 and the last SLBM passenger train leaving here in 1969. Today, an average of 12 Union Pacific trains travel through Odem each day, plus four to six TFM trains.

Traveling north of Odem, it is possible to virtually parallel the Sausage for another 19 miles (to Mathis) using parallel farm roads. Today, the Union Pacific has but three passing tracks between Corpus Christi and San Antonio; one at George West, one at Campbellton and one at Pleasanton. Clearly, as trains go in both direction on what is otherwise single track, there can be some delays, with trains seemingly idling at a siding while the train given the highest priority by dispatchers comes through.

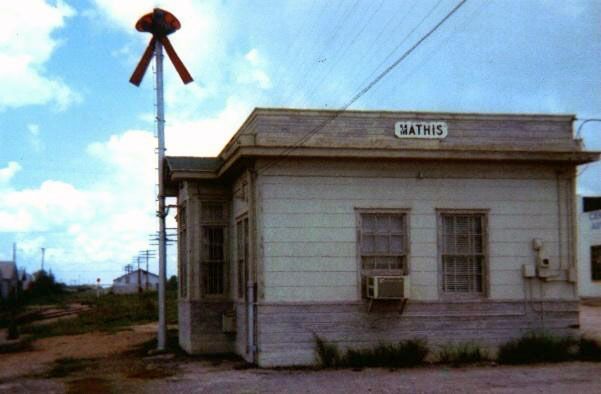

Mathis is where the Sausage crosses the old Alice Branch of the 'S.A. & A.P.' The San Antonio and Aransas Pass arrived here first in 1887, and established their station downtown. When the Sausage got here in 1914, it might have made sense to establish a “Union” station at the diamond, but unfortunately this was another of those irreconcilable Texas and New Orleans versus Gulf Coast Lines squabbles. As at Sinton, there would be two stations, each barely a quarter a mile from the other. The original 'S.A. & A.P.' line through Mathis (and on to Skidmore 14 miles distant) has been lifted north of this spot, but a tiny stub of what was once main line remains. When the Southern Pacific quit all service to the Rio Grande Valley in 1980 (ending their dream), rival Missouri Pacific bought this ¾ mile stub to serves a large grain elevator. From the condition of the track, the traffic on this stub seems to be a trifle sparse.

Twenty five miles further north from Mathis is George West, population 3000, 62 miles from Corpus Christi, and site of the first passing track out of Corpus Christi (other than the Viola yard). From here, you can get a northbound view of the main and passing track plus the site of the old passenger station just beyond the road crossing on the right. To the south are two sidings serving local industry, plus the passing track. George West became the county seat of Live Oak County in 1919 after the railroad came through, taking this role from nearby Oakville, which failed to get a railroad connection. It had been county seat since 1856. It used to be a significant stop on stage coach runs between the coast and San Antonio. George West, the man, donated land on his own property for the railroad and the rest, as they say, is history.

Three Rivers, population 2,000, the next town along the line, provides a substantial amount of traffic to the railroad from its oil refinery. This is owned by Valero and is in yet another phase of expansion. Rail service provides this important part of the local and regional economy with a safe and environmentally friendly way to move the huge quantities of product and raw material involves in the refining process. It is not uncommon for fresh crews to be delivered to trains awaiting departure from the refinery.

The next passing track is at Campbellton, which today is a very small place. It was an official stop on the SAU & G but it was probably too small even then to rank an actual depot. The town stretches along the line of the railroad with the highway on the other side. Apart from the rail line, there really isn't much at all to see.

Just to the north of Campbellton is a lengthy rail spur, heading west, that serves the San Miguel power plant. It was established in the 1980s, remarkably close to the town of Christine, which was once served by another short line road that was purchased by Missouri Pacific, but pulled up in the early 1940s. The plant burns Texas lignite coal, and, according to its builders, is noted for both its environmentally sensitive operations and its low cost of production. The rail spur was purpose built to serve the plant.

McCoy, the next place we reach, is another town that was create by the railroads. At one point it had a depot, a post office and a school with a population in the hundreds. Today it is under thirty, with the school long gone. The railroad still runs through, however, with occasional crew changes on trains whose crews have 'died' here. Sometimes trains are halted on the mainline, when congestion is really bad, and after a crew's allowable service time has run out, which is known as dieing by the railroad, they will be replaced, right on the mainline by a fresh crew that will arrive by road vehicle.

The next stop on the line is Pleasanton, which looms very large in the "Sausage" legend. It was here that the company had its headquarters. The line from Crystal City to the west used to connect to the line between San Antonio and Corpus Christi just to the north of the town, where there is now a golf course. In fact, there used to be two Pleasantons, and each had its own depot, just over half a mile from each other. A regular country town depot graced the original Pleasanton. A more imposing two-story masonry structure graced North Pleasanton, with the company offices upstairs. Also, there were engine yards, complete with turntables, and any number of buildings and operations associated with running a railroad, including a large vat for dipping railroad ties in tar to prolong their service life. When the S.A.U. & G. was taken over by Missouri Pacific, the yard and company headquarters in Pleasanton were closed down, and maintenance operations moved to San Antonio. However, the site of the old yard remains undeveloped. If you are feeling intrepid, you can beat through the undergrowth and find the pit that housed the turntable. The larger of the two depots was abandoned and demolished in the 1950s. Its site, too, is still vacant. The other depot was moved from its original site when the main road through town was improved. After passenger service ceased, it was kept for freight use and for track crews. Eventually, it too was deemed surplus to requirements. Fortunately, the Union Pacific was generous enough to donate it to the town, and it was moved to the Longhorn Museum on the edge of town, quite a long way from the actual railroad itself. The modern siding, where you can frequently see trains waiting, is north of where the line crosses the main road through town. The connection to the line that ran to Crystal City is further north still, more or less where the modern siding ends, near the golf course.

You follow Highway 281 back to San Antonio, with the rail line beside you just about all the way. You will soon be able to see the new Toyota plant. The existence of this line made it possible for San Antonio to attract this plum economic development. Access to more than one railroad company along this stretch of line became quite a talking point as trackage rights were not given to the BNSF when Union Pacific acquired Southern Pacific. Fortunately, this has been resolved, and it may come to pass that we shall see trains other than those of the Union Pacific on what was their jealously guarded territory since they merged with the Missouri Pacific in 1982.

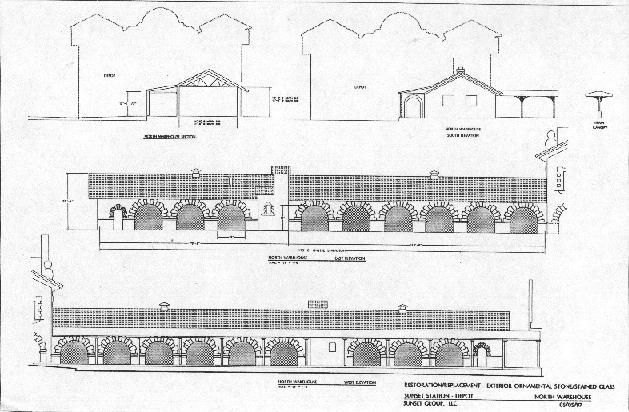

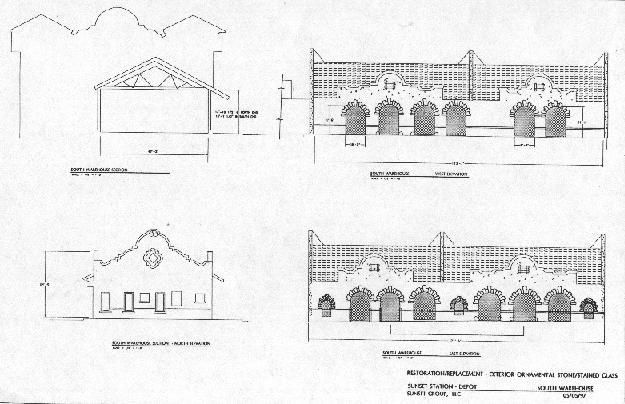

The old "Sausage," once the most impecunious of railroads, merges with the main line to Laredo, built originally by the International & Great Northern, about three miles south of the city, just before the huge South San rail yard. A little further along the line, the very grand I & GN station, where passengers would have boarded on their rail journeys on the "Sausage," is still there but is now a credit union. It has been a very long time since 1970, when it last had even a MOPAC rail customer, and even longer since it had one from the "Sausage."

San Antonio, Uvalde and Gulf Passenger Service In Its Prime

The year 1937 marked the time when many railroads recognized the realities of the Great Depression and the needs of the erstwhile ignored “coach” passenger. In an effort to compete with the automobile, passenger trains were to be “streamlined”, air conditioned, fitted with comfortable reclining seats for coach passengers, and speeded up. This was the year the Missouri Pacific introduced its first "Eagle" passenger train (Between Omaha and St. Louis), with at least six additional Eagles to follow on other routes as a brand name for their premier trains had been established. The Rock Island had their "Rockets," the Burlington had their "Zephyrs," the Milwaukee Road had their "Hiawathas," and Texas and New Orleans (The Southern Pacific) introduced their mile-a-minute streamliner between Dallas and Houston called the "Sunbeam." A depression-weary country responded favorably to these new, fast trains. Even on secondary runs, such as San Antonio to Corpus Christi, there was a clamor for better service. The Sausage (Missouri Pacific) responded. Its day train between San Antonio was #205 southbound and #206 northbound. These trains were given the name "Texas Triangle." They were equipped with air-conditioned coaches and a food service car, plus a first-class sleeping car to Fort Worth. They would cover the 150 miles, making just seven intermediate stops, in a record 4 14 hours, averaging 35 m.p.h. Considering the roads of 1937, this was a respectable speed and would indeed become the all-time record. Would the S.A.P. respond with their own speed-up? Actually, no. As a harbinger of things to come, the Southern Pacific not only refused to compete, it withdrew its day train out of San Antonio.

Gulf Coast Lines (Missouri Pacific) continued to aggressively pursue passenger train potential. It introduced its very own Eagle, dubbed "The Valley Eagle" (Houston, Corpus Christi, Brownsville) in 1950. This train dashed over its 371-mile route from Houston to Brownsville in just 8 12 hours, at an average speed of 44 miles per hour. This was the final call for the Southern Pacific to stand up and fight! Instead of fighting for market share, the S.P. simply withdrew from all passenger service in 1952. The "Border Limited," introduced with such great hope and fanfare in 1927, lasted just 25 years. The Southern Pacific Railroad, which had expanded into the Rio Grande Valley in 1927 using S.A.P. lines, had intended to become a full partner in freight traffic to South Texas. 53 years after its expansion in 1927, Southern Pacific abandoned virtually all track in deep south Texas, often referred to as "The Valley."

Missouri Pacific abandoned passenger service to Corpus Christi and the remainder of South Texas in the early 1960s. Following MOPAC's merger with the Union Pacific, the lines built by the San Antonio, Uvalde, and Gulf and the St. Louis, Brownsville, and Mexico continue to provide the area with a significant amount of its rail freight needs.

The Last Shall Be First: Thoughts on the S.P.'s and

the Missouri Pacific's service to Corpus Christi

In the case of railroads, the first of the two companies to serve a route is usually the one to survive a shakeout. By historical precedent, the 'Sausage,' an early 20th-century railroad to Corpus Christi, should have, despite its superior engineering, fallen behind the 'S.A.P.' and failed. The S.A.P.’s intermediate towns of Floresville, Beeville, and Sinton easily outrank the Sausage’s Pleasanton, George West, and Odem. So why did the sausage beat the odds and outlive the S.A. and A.P.?

The answer probably has everything to do with the management style at the Southern Pacific Railroad. Should it improve the former San Antonio and Aransas Pass and really compete with the newly formed San Antonio, Uvalde, and Gulf, or should it downgrade the S.A. and A.P. system? The Southern Pacific seemed ambivalent toward its position. Nowhere was that more obvious than in their major expansion into the Rio Grande Valley. The first thing the S.P. did to the S.A. & A.P. upon being allowed, finally, in 1925, to legally acquire the line, over which it had been in de facto control since 1892, was to downgrade its entire operation to secondary status. Then, in 1927, the S.P. tried to expand their operations in south Texas, using much of the S.A. and A.P. to do so. How could it enter the Rio Grande Valley without knowing which way it wanted to go? Doing it on the back of an enfeebled S.A.P. frittered away the capital the Southern Pacific did spend on the Valley extension.

Who knows what was going on in the minds of the Texas and New Orleans planners in Houston? Maybe their San Francisco masters were just too far away for the railroad to develop a cohesive strategy for their south Texas operations. The S.P. was never very good at tolerating competition. It regarded resources as being scarce and felt it needed to be in a monopoly position in order to thrive. Corpus Christi was never part of the overall Southern Pacific strategy for Texas. Houston was it's baby, and other ports were just a distraction. There is no doubt that the city of Corpus Christi knew it needed a different company to provide it with adequate rail service way back in 1912, when it was still struggling to get government assistance with the creation of deep-water port facilities. It bet on a struggling independent company and helped change the destiny of the S.A.U. & G. in more ways than one. In the 1960s, Corpus Christi shrugged off the loss of the Southern Pacific without much concern. Its freight was carried quite adequately by the Missouri Pacific. The S.P. completely failed to develop a strategy that would give it a substantial amount of the increasingly lucrative business opportunities in this area. Its all-or-nothing approach yielded a not too difficult-to-understand result: nothing.

Transportation Museum

CONTACT US TODAY

Phone:

210-490-3554 (Only on Weekends)

Email:

info@txtm.org

Physical Address

11731 Wetmore Rd.

San Antonio TX 78247

Please Contact Us for Our Mailing Address

All Rights Reserved | Texas Transportation Museum